Books

Personality

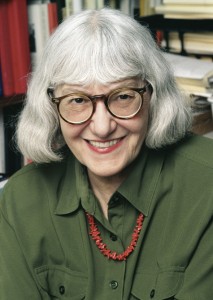

Profile: Cynthia Ozick

Sometimes, when Cynthia Ozick is looking for a word, she holds her head, closes her eyes and tries to physically claw it out of the air.

Her obsessive search for just the right words to fashion the “comely shape of a sentence” translates into prose burnished with sensuality, glimmering with precision and threaded with metaphor and almost accidental humor.

For Ozick, writing is not a choice, but “a kind of hallucinatory madness,” she notes. “You will do it no matter what. You can’t not do it.” The “freedom in the delectable sense of making things up” coexists with the “torment” of writing. “It’s hard to write a sentence. It has to come out of the sentence before and anticipate the sentence to come. It has to have a certain cadence and a clarity of meaning and insight.” Ozick is so devoted to the Word that the very notion of pastimes shocks her. “Hobbies? Oh, no! What would they possibly be? Even the idea is absurd. I am a tireless reader but I wouldn’t call reading a hobby. It’s a drive, a hunger, a thirst. If a day has to pass that I haven’t read I suffer.”

Shelves of books greet visitors in the hallway of Ozick’s red-brick home in Westchester County, New York. Though midafternoon, it is toward the beginning of Ozick’s day; she often starts writing around 10 P.M., works through the night and rises by noon. Petite in an olive-green blouse and black skirt, her signature silver pageboy haircut and her unlined face adorned only with lipstick and set off by owl-framed glasses, Ozick is far from the ferocious and intimidating personality her polemical writing projects. Solicitous and welcoming, she serves tea and cookies on English china in the formal dining room, pointing out her most treasured possessions: four brass Shabbat candlesticks that her maternal grandmother, Rachel Regelson, brought with her from Russia in 1906.

Ozick learned her first lesson in feminism at age 5 when Regelson tried to enroll her in heder. “The rabbi said, ‘Take her home. A girl doesn’t have to learn,’” Ozick recounts. But her grandmother insisted she be accepted. Ozick outshone the only other student in the class, a 6-year-old boy. “At the end it was such vindication. The rabbi said to my grandmother in Yiddish, ‘goldene kepele’—she has a golden little head.” Ozick’s feminist sensibilities led her to keep her own name when she married attorney Bernard Hallote 60 years ago.

She recalls being a “pious child” with a passionate Jewish commitment passed down from her grandmother and her parents, Celia and William. Her father fled the czar’s conscription in 1913, armed with a complete secular and Talmudic education and a fluency in languages. He opened a pharmacy in the neighborhood then known as Yorkville (East Eighties), where Ozick was born, before relocating to the Bronx. An artist by avocation, her mother was a “firebrand” who demonstrated on behalf of Jewish issues well into her eighties. Ozick sees herself as a combination of her parents’ traits: reticent and reckless.

Her intense Jewish consciousness continues to flourish. “I am completely Israel-obsessed, morning, noon and night,” Ozick reveals. “I can’t stop reading, and thinking, and feeling terrible apprehension. The situation has made me pay much more attention to politics than I ever did. I confess to more anxiety than members of my family who live there.” She has traveled to Israel frequently, both as a visiting writer and to see family—a nephew who made aliya; children and grandchildren of her maternal uncle, Hebrew poet Avraham Regelson; and relatives who fled Stalin.

Regelson’s literary path made it easier for Ozick to pursue hers. By way of the “fattest books” from the traveling library that stopped in her neighborhood twice a month, she was transported to faraway worlds. At 17, she discovered Henry James’s “The Beast in the Jungle,” a novella about a man who waits his whole life for something huge and tremendous to happen to him. “He waits…for this cataclysmic event to overtake his life. At the end he makes the discovery that it has already happened, and what it is, is that nothing has happened,” says Ozick. “I had this eerie feeling at 17 that it was the story of my life.” In fact, she notes, it is true of every life.

At Ohio State University, Ozick focused her master’s studies in English on James’s novels. For seven years, she worked on a philosophical novel, Mercy, Pity, Peace and Love (its title based on a quote from William Blake), writing 300,000 words before abandoning the project. She labored for another seven years on Trust, a massive novel about every possible kind of distrust. It was published in 1966, a few months after she gave birth to her daughter, Rachel. Ozick then turned to the short-story format, achieving critical success with The Pagan Rabbi and Other Stories

.

Author Lore Segal, a friend of 45 years, recalls when her husband, David, an editor, agreed to publish Trust (Mariner)—if Ozick would make his suggested changes. Ozick’s answer? No. He published it as she submitted it, Segal recalls. “She’s absolutely unpersuadable about how a sentence reads…. She is her sentence, and you can’t alter it.” Segal calls Ozick a “wonderful, rich, brilliant and inventive writer who is afraid of nothing in her writing.”

No stranger to long-term projects, Ozick has kept a diary since 1953; she fills about two volumes a year. She also answers every letter she receives. Literary scholar Edward Alexander has amassed hundreds of letters and e-mails from a 37-year correspondence and friendship with Ozick. “Cynthia is the most cheerful gloomy person I know,” he says, a shrewd and “ïmpish” observer of human behavior and a loyal friend. He recalls her response when he sent regrets that he would be unable to attend a reading she was giving in Seattle because he had to take his grandson to Hebrew school. “‘Philip’s soul,’” she said, “‘is more important than my reading.’” Ozick, he says, “has become a figure and a force as well as a writer. Her distinguishing mark of character is courage…. Her unique contribution has been the Jewish one of converting imagination into a moral instrument.”

In reviews of her latest novel, Foreign Bodies (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; see our review here), critics continue to note what they perceive as Ozick’s Jamesian ardor in recasting the plot of his masterpiece, The Ambassadors. Ozick counters that her interest in James is exaggerated. “The plot is the least of it,” she says. “A young man leaves home to seek his fortune. That’s a fairy-tale plot that preceded The Ambassadors.” More importantly, she clarifies, James depicted Europe as the seat of high culture and civility, and America as raw, provincial and crude. In Foreign Bodies

, she portrays a Europe sodden and reeling from the Holocaust, and America, though imperfect, as a haven for pluralism and freedom, the country that saved Europe from Hitler.

Ozick is officially “against” writing about the Holocaust but unintentionally it creeps into all her writing. One of her most poignant and lacerating short novels, The Shawl (Vintage), provoked disbelief that she is not a survivor; it is now required reading on many Holocaust lists. “I’m roughly Anne Frank’s age,” says Ozick. “If I had been in Europe and not here I would be dead, which is something I can never forget.” In addition, anti-Semitic stone-throwing, name-calling and humiliation marred her own early childhood. Though she went on to have a happy adolescence, in hindsight she cannot reconcile her “extraordinarily joyful” high school years when she was “reading German and loving Heine and Goethe and Schiller” with what was happening at the same time to teenagers across the ocean.

The theme of deceit pervades both her writing as well as her notion of writers. “Writers are in general completely untrustworthy,” she says. “They are tempted to include traits of people they know and make enemies, no matter how they disguise them.” A story about her Russian cousin tumbles out. “I lost her affections after 70 years of the families’ separation. We corresponded…and reunited in Israel. Then I wrote a story in Puttermesser Papers (Vintage), ‘The Muscovite Cousin.’ The cousin in the story was a kind of hero. But my cousin broke with me because she recognized a fictionalized version of her daughter…and we became estranged. I’m heartbroken…. And that’s why writers are dangerous. They hurt people. Do they express remorse? Never.”

It is easy to mine Ozick’s fiction for biographical nuggets. She writes from the place of who she is and what she knows, but, she stresses, the imaginative process allows her limitless possibilities. She burrows deeply and surprisingly into the minds and hearts of different characters. They include the amanuenses to Joseph Conrad and Henry James (Dictation); the leg of a mosquito or the leg of a chair; and Ruth Puttermesser, a lawyer who becomes mayor of New York—succeeding Malachy Mavett, an allusion to the Angel of Death—and fashions a golem. It is no wonder that one of her favorite words is preternatural.

Ozick’s daughter, Rachel Hallote, associate professor of history at SUNY Purchase and head of its Jewish studies program, is an archaeologist who lives nearby, as does Ozick’s brother, Julius, a retired dentist. This summer, Hallote opened a new dig in Israel at Tel Hesi, near Sderot; her two children—Samuel, 15, and Rose, 12, who attend day school—participated. Ozick and her husband belong to a traditional synagogue.

Her place in the American literary canon does not automatically translate into sales and readership. But writers write because they must, she reiterates: “Who survives [after they die] is an interesting question. You have to be Saul Bellow to survive.”

While Ozick’s fiction brims with Jewish characters and themes, she disparages the concept of a “Jewish novel.” “What is a Jewish book?” she asks. “Torah, Talmud, a work by Maimonides or Soloveitchik. If I pick up a novel and it’s going to be a ‘Jewish’ novel in the sense of uplift, a sermon, a polemic or something saccharine, I’m going to throw it against the wall. Is a novel a Jewish book? Sure, but not in the sense of being didactic. A work of imagination cannot be a tract.”

Her 1970 essay that expounds on imagination as image-making, literature as idolatry and therefore in conflict with monotheism, provokes Ozick’s ire: “I want to bury that essay, I want to shred it. I want to destroy it, never have it surface again.” Essays are also a kind of fiction, she explains. Both are built out of intellect and imagination, but an essay rests more on the intellectual, and fiction rests more on the imagination. “Neither can be trusted,” she states. She is currently working on a new short story. As with all her writing, she will complete the draft in longhand before transferring it to a computer.

Ozick’s heroes include Ruth Wisse, scholar and literary and social critic, “for her intellect, courage and her profound understanding of the nature of Jewish fate,” and British journalist Melanie Phillips, who writes a controversial column on social and political issues. She admires British novelist Howard Jacobson, “the bravest Jew in England,” who won the Man Booker Prize and Hadassah Magazine’s Ribalow prize for The Finkler Question.

Despite 25 published works, she wishes she had written more. “Life interrupts,” she acknowledges. “For me this is almost a mantra. And what emerges from that is my deepest desire: the freedom to write always and always and always.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply