Arts

Exhibit

The Arts: Social Justice in Clicks and Snaps

for the Morning Trade.’ All images courtesy of The Jewish Museum, NY.

Max the bagel man is beaming, bathed in light; looped in each hand are two strings of bagels that he is rushing to a restaurant on Second Avenue in the early morning. He is almost suave in a tie and the suit jacket he wears buttoned over his long apron and boots. Behind him, a goose-necked street lamp points downward, a delicate counterpoint emerging from the dark hulk of New York’s buildings.

The black-and-white image from 1940 is part of a new exhibition at New York’s Jewish Museum (212-423-3200; www.thejewishmuseum.org) that explores the artistry, history, social and political contributions of New York’s Photo League, which flourished from 1936 to 1951.

Entitled “The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951,” the exhibit’s 150 photographs showcase the work of the largely Jewish, first-generation American group that blended esthetics and social activism in documentary photographs and focused on the ordinary people of their city’s streets and neighborhoods. The photographs are drawn from the collections of The Jewish Museum, where the show remains through March 25, and Ohio’s Columbus Museum of Art, where it will be on display from April 19 to September 9. It will continue on to the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco and the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida.

Max is buoyantly photographed by Weegee (real name, Arthur Fellig), a Galician-born photojournalist nicknamed (think Ouiji Board) for his uncanny arrival on the scene of a crime, fire or other emergency just minutes after it occurred (he actually owned a police radio). Many of Weegee’s other photos—and those in the show—center on the grim realities of urban life. In Manuelda Hernandez Holds Manuel Jimenez In Her Lap, for example, a white policeman tries to disengage a woman weeping over her sailor-boyfriend, shot by a rival at a West Village bar.

The photographs’ emotional impact is part of the league’s legacy, both to viewers and to subsequent generations of street photographers. Cocurator Mason Klein defines the league’s work as the “subjective, poetic renderings of social impressions” that transformed the medium by pioneering the idea that documentary photography must have a personal perspective. The city became a classroom where leaguers could study social relations, he notes. On a practical level, their passion was well served by the advent of small, hand-held 35-mm cameras, which allowed a new kind of “chance” photography, “at once casual and purposeful,” says Klein, and new “picture-hungry” illustrated publications like Life and Look.

“We feel deeply about the people we photograph, because our subject matter is our own flesh and blood. The kids are our own images when we were young,” said photographer Walter Rosenblum, who led a group project on Pitt Street, a stretch of blocks on the Lower East Side not far from where he grew up. Unlike Group f/64, the largely non-Jewish, West Coast counterpart cofounded by Ansel Adams, the league did not photograph nature because its members lived amid concrete and brick. They captured the patchwork of street signs, storefronts and subways, bars, parades, demonstrations and dancing schools. They explored Hester Street and Harlem, tilted perceptions of the Empire State Building and Penn Station, and unfolded the layered narratives of the city’s denizens: immigrants, shoeshine boys, shoppers and beachgoers. When they traveled beyond the city, they examined issues of race, violence, poverty and politics, condensed in Marion Palfi’s In the Shadow of the Capitol from 1948.

The exhibit’s Jewish link hinges on social justice as a compelling force for league members, says Klein. Organized chronologically from “Precursors” to Depression and cold war, the show presents black-and-white photographs hung starkly against gray walls, punctuated by wall quotes. It opens with film excerpts that carry eerie overtones of today’s “Occupy” movement—except that these hail from the Workers Newsreel Unemployment Special, produced by the Film and Photo League in 1931. Five years later, the group’s photographers split from the filmmakers to form the Photo League.

Though it remained committed to progressive goals, the league slowly moved toward becoming a center for American photography, adapting to dizzying historical events and reflecting the complexity of its diverse membership. Nonetheless, it was blacklisted in 1947 by the United States Attorney’s Office as an organization considered “totalitarian, fascist, communist or subversive,” and never recovered. The league’s artistic impact has rarely been recognized, states Klein, adding, “We have to rectify history.”

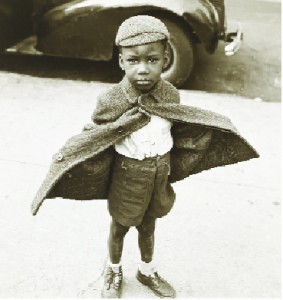

Most of the images in the exhibit chronicle a mere 15-year span, but they speak on a universal level to the human condition—focusing especially on children. League photographers portrayed children with empathy but without sentimentality, writes cocurator Catherine Evans in a catalog essay (Yale University Press). They explored the themes of “innocence in a rough world, playfulness in harsh contexts; and the pathos of the vulnerable individual.” Sonia Handelman Meyer’s closely cropped Boy in Mask, Harlem cuts out all incidental information to home in on the child’s haunting eyes and masked mouth. A game of cops and robbers turns into an “uneasy metaphor for the stifling of speech,” writes Evans, as Meyer’s photo asks, “Are things what they appear to be?” Jerome Leibling’s dignified Butterfly Boy does not betray the child’s impoverished circumstances. In other images, the photographers capture the panorama of childhood at a distance: soaring on a swing at the foot of the massive Williamsburg Bridge (Walter Rosenblum); and jumping from the roof of a three-storied building into the Hudson River (Ruth Orkin).

Even before the league’s official founding, photographers like Lewis Wickes Hine trained their lenses on portraits that lifted individuals out of abstraction. “I have always been more interested in persons than in people,” said Hine, a sociologist and teacher. Hine conveyed to his students “that understanding what made photography good required understanding what made good art,” writes Klein in the catalog. Children already take center stage. In Danny Mercurio, Newsie, Washington, DC from 1912, Hine depicts his subject by name, a newsboy in knee pants and black stockings, the brim of his cap almost reaching his eyes, a stack of newspapers under his arm. To his left, a stern bourgeois matron throws a disdainful glance at him—a metaphor for public indifference. Hine’s photos for the National Child Labor Committee hastened the development of child labor laws.

Hine taught Paul Strand, another inspirational figure, who moved away from the prevailing “pictorialist” school of soft-focused, painterly, sometimes staged photos to embrace abstract forms drawn from real life. Wall Street, New York, which Strand originally wanted to call Pedestrians Raked by Morning Light in a Canyon of Commerce, shows exactly that: men, women and their shadows dwarfed by an imposing new J.P. Morgan building.

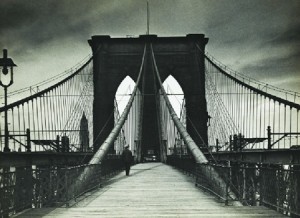

In fact, as much as league photographers were concerned with people, they also found their inspiration in architecture. Alexander Alland pairs two views of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1938, one that tells the narrative of its construction, a tumble of masonry lending a mysterious air to the span peering out in the background—and a more formal, straightforward portrait. In an upwardly mobile postwar society a decade later, Erika Stone captures an advertisement painted on a tenement wall of a well-dressed blonde woman looking away from the grimy building to her right (Lower Eastside Façade).

As the league fostered the evolution of documentary photography, it spearheaded innovative programming, offered classes, debated straight documentary approaches as opposed to artfully constructed images, published a newsletter (“Photo Notes”) and provided exhibit space. It became a forum for Camera-derie, a salon of sorts. Many members were young and poor; some went without food and clothing in order to buy lenses and photographic paper. The league charged little, offered scholarships, brought people together and sent them out to learn by doing. It sponsored Crazy Camera Balls, costume parties where members were encouraged to come dressed as their favorite photos, and Photo Hunts, scavenger hunts in which leaguers fulfilled random, sometimes absurd, assignments.

Sid Grossman, the league’s visionary and provocative cofounder (at 23), shaped its pivotal role. “A photograph is as personal as a name, a fingerprint, a kiss,” said Grossman. Producing a good photo that moved the viewer involved more than technique for Grossman. The subject had to be as expressive as possible, achieved partly through the specific relationship between photographer and camera. By exploring the body language, facial expressions and positioning of two brothers in Shoeshine Boys, Harlem, Grossman deepens the psychological dimension of the photograph while remaining attentive to artistry: the geometrics of the store window, the shoeshine kit and the shadows on the sidewalk. The photograph hints at Grossman’s “penchant for alighting on the anecdotal, animated, and complex subject,” writes Klein.

Grossman traveled through the Dust Bowl in 1940 to photograph homesteaders still suffering from drought and dust storms that had swept the region during the Depression. In Henry Modgilin, Community Camp, Oklahoma, he dramatizes the angular body of a farmer and union organizer. In the darkroom, Grossman highlighted each finger of Henry’s gesturing hand so it makes the picture burst, says Klein. Grossman’s stint in Panama with the Air Force Public Relations Section (1945 to 1946) kindled a new approach that broke the rules of accepted photography. In Jumping Girl, Aguadulce, Panama, blurred images and flash photography create a pictorial experience with a life of its own rather than just a record of an event.

from Harlem Document.

Like Grossman, who insisted on fighting fascism, half of the league’s members enlisted during World War II. Paul Strand registered his horror in Swastika (a.k.a. Hitlerism), draping a crucified skeleton on a swastika. Rosenblum became a decorated Army photographer. He recorded his experiences of landing in Normandy on D-Day in German Prisoners of War, Normandy, and D-Day Rescue, Omaha Beach. Ironically, three years later, the league was charged with being unpatriotic. Angela Calomiris, an FBI informant and league member, denounced Grossman as a Communist and named the league a front organization. Grossman resigned in 1949 and withdrew to Provincetown, Massachusetts. A “coda” to the show offers his last picture (Provincetown): seagulls swirled in a frenzy of light and dark, mirroring the poisonous atmosphere he had endured, according to Klein. Grossman died in 1955 at age 43.

Grossman influenced Viennese-born, Paris-educated Lisette Model, who went on to teach at the New School for Social Research and became a mentor to Diane Arbus and others. Her confrontational portraits of those on the margins of society shift from triplets in the Bowery to the transvestite performer Albert-Alberta, whose act was part of Hubert’s Forty-Second Street Flea Circus in Times Square. “Don’t shoot until the subject hits you in the pit of the stomach,” Model said. She evokes the rhythm of everyday life in the faceless Running Legs, zeroing in on the angle of a long coat and trouser-clad leg hurrying along a sidewalk.

Model is one of the many women league members represented in the exhibit. According to Evans, over 100 women participated in league activities—about one-third the number of men—serving in capacities from treasurer to president. They joined because of the league’s inclusiveness and compassionate focus as well as its inexpensive darkroom privileges. The league welcomed women, “maybe because it in itself was new and not burdened with centuries of tradition,” Evans posits. Some continued careers in photography after the league’s demise; others disappeared from history.

Lucy Ashjian is a case in point. Though she served as league vice president, her story only unfolded when her niece, art historian Christine Tate, discovered over 200 negatives and 120 vintage prints in 2003. The daughter of Armenian refugees who settled in Indianapolis, Ashjian was a college graduate whose work emphasizes oppression within the context of modernism. Untitled (Relief Tickets Accepted) depicts Epstein’s Clothing, a store on the Bowery that survived the Depression by allowing customers to pay with government relief tickets. In Untitled (Group in Front of Ambulance), she places the vertical, still figures of a black man, a mother holding a baby and other bystanders at different vantage points to create a frozen urban vista.

Ashjian participated in the Harlem Document, the league’s longest-lasting project, which occupied 10 photographers from 1936 to 1940 and produced dozens of photos shown in exhibitions around the city. Organized by Aaron Siskind, its goal was to record a community in peril and advocate for it. Ironically, the photographers were exclusively white; the only African-American involved was writer Michael Carter, who wrote an accompanying sociological study. Despite the group’s good intentions, its study was filled with stereotypes. For example, when Look published Jack Manning’s Elks Parade as the cover photo for its 1940 story, “244,000 Native Sons” (borrowing from Richard Wright’s novel), it interpreted the photo of Harlem residents gathered on fire escapes as a symbol of overcrowdedness. In fact, the image depicted an ebullient celebration of the Elks’ 40th-anniversary parade that drew thousands of spectators.

Some of the images are optimistic. Siskind’s The Wishing Tree shows a group of boys in fedoras and coats gathered around a tree stump—all that was left of Harlem’s legendary elm, said to bring good fortune. When it was cut down in 1934, tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson moved the stump to a nearby block and planted a new Tree of Hope beside it.

Issues of civil rights intrigued Rosalie Gwathmey, who photographed African-Americans in her native Charlotte, North Carolina. Untitled (Sunday Dress) from 1945 portrays an elegant elderly woman in her Sunday hat and shawl. Shout Freedom, Charlotte, North Carolina is a bittersweet commentary on the lack of freedom in the South in the 1940s. It depicts a black girl walking through a vacant lot. A white sign on the wall behind her is festooned with letters advertising a musical that celebrates the American Revolution.

League photographers also shot scenes of culture and leisure: Richard Lyon’s Cabaret Dancer Going on the Stage, top hat in hand, bubbles with life, while Weegee’s barebacked, coiffed Woman at the Met is a more enigmatic presence. You can almost see Morris Engel and Sid Grossman winking wryly behind the lens in their off-kilter Coney Island beach shots. Even in scenes that seem trivial, leaguers reveal a kaleidoscope of emotions: from the grimaces of the little girl and organist in Lee Sieven’s Salvation Army Lassie in Front of a Woolworth Store to the anticipatory grin of a worker about to devour his sandwich in Bernard Cole’s Shoemaker’s Lunch.

Whether their photos were poignant, brooding or lively, leaguers lived by the credo Model invoked. “The thing that shocks me and which I really try to change,” she said, “is the lukewarmness, the indifference, the kind of taking pictures that doesn’t matter.”

Rahel Musleah’s Web site is www.rahelsjewishindia.com.

Credits:

‘Max Is Rushing in the Bagels to a Restaurant on Second Avenue for the Morning Trade’ c. 1940, gelatin silver print/The Jewish Museum, NY/Purchase: Joan B. and Richard L. Barovick Family Foundation and Bunny and Jim Weinberg Gifts. © Weegee/International Center of Photography/Getty Images

‘Butterfly Boy,’ New York, 1949, gelatin silver print/The Jewish Museum, NY/Purchase: Mimi and Barry J. Alperin Fund. © Estate of Jerome Liebling

‘Untitled (Brooklyn Bridge),’ 1938, gelatin silver print/The Jewish Museum, NY/Purchase: William and Jane Schloss Family Foundation Fund. © Estate of Alexander Alland Sr.

‘Playing Football,’ c. 1939, from Harlem Document, 1936-40, gelatin silver print/George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film, Rochester, New York/Gift of Aaron Siskind. © Estate of Harold Corsini

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply