Israeli Scene

News + Politics

Letter from Jerusalem I: Much Ado About Nothing?

August 3 Strategic Affairs Minister Moshe Ya’alon is so close a political ally of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that he sometimes seems to be speaking the prime minister’s thoughts in a deeper voice. In his office at the Defense Ministry in Tel Aviv, Ya’alon thumped his large hands on his desk as he spoke about the expected United Nations vote recognizing Palestine as an independent state in September. The Palestinian bid for recognition, Ya’alon asserted, was proof that Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas fears direct negotiations with Israel and the hard choices needed to make peace. Yet in the form the United Nations decision is most likely to take, Ya’alon admitted, “it will have no meaning on the ground.”

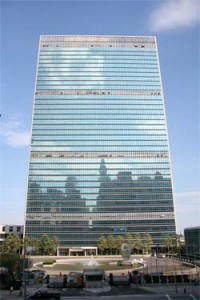

Photograph by Stefan Schulze/WikiCommons.

In the latest of his political posts, Ghassan Khatib serves as the spokesman of Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s government. Khatib’s office in the new government media center in Ramallah looks out at other freshly built stone-and-glass office towers. The Palestinian decision to seek United Nations recognition, he said, was due to Israel’s inability to stop building settlements and start negotiating in good faith. He described the vote as momentous, signaling that the international community would take responsibility for implementing a two-state solution. What effect would the vote have on the ground in the West Bank? “Maybe nothing,” Khatib admitted.

If you feel confused, you have been paying attention. Here’s a distillation of Israeli and Palestinian opinion, gleaned from government leaders, academic analysts and common citizens on both sides: The vote in the United Nations General Assembly recognizing Palestinian independence will be a cataclysmic event that might not actually happen. If it does, no one can describe any effect it will have on daily life in the ostensible territory of the newly recognized state. Both its eager proponents and those desperately trying to prevent it are certain it will alter Israeli-Palestinian relations—but neither can predict how.

Add one more contradiction: Despite the panicked tones of Israel’s government, a General Assembly vote recognizing Palestine within the pre-’67 boundaries of the West Bank and Gaza could be regarded as a diplomatic victory for Israel. The disaster warnings are thoroughly misleading.

The common element in Israeli and Palestinian readings of the United Nations gambit is that 20 years of peace talks have not produced a peace agreement. Over a third of today’s Israelis and more than half of West Bank Palestinians were born since the 1991 Madrid Conference marked the start of negotiations. When the Oslo Accord was signed in 1993, it posited “a transitional period not exceeding five years” leading to a permanent agreement. Today, the “transitional period” seems permanent.

Additionally, it has been over six years since Mahmoud Abbas replaced Yasser Arafat as Palestinian Authority president. He is the strongest advocate in Palestinian politics of reaching a two-state arrangement via direct negotiations with Israel. He regards the violence of the second intifada as a strategic disaster for the Palestinians. Not only that, said Israeli scholar Menachem Klein, “Abbas sharply opposes nonviolent civil resistance,” which he sees as inevitably leading to violence. Instead, he has promised his people a top-down solution through diplomacy.

In contrast, Fayyad’s strategy has been to build a state from bottom up. He has been prime minister for four years, since the split between Hamas-ruled Gaza and Abbas’s Fatah-dominated West Bank regime. An American-educated former International Monetary Fund official, his goal has been to create governing institutions and a flourishing economy so the Palestinian Authority can present the world with a working state.

Fayyad and Abbas can point to some success. The P.A.’s police and security services have restored order to West Bank cities—and worked closely with Israel to end terror attacks. In downtown Ramallah’s shopping district, Hiba Odeh, a 25-year-old mother of three, told me happily that public minibus drivers have begun observing the law against overpacking their vehicles. Al-Quds University political scientist Abdel Majid Sweilem praised Fayyad for ending financial chaos in the authority. Government-provided health care is nearly universal, he said. As a result of the government’s strategy, he asserted, Palestinians have freed themselves from the “cantons” of terrorism and corruption. An IMF report earlier this year said that the Palestinian Authority is “now able to conduct the sound economic policies expected of a future well-functioning Palestinian state.”

But Abbas and Fayyad haven’t delivered independence. West Bank Palestinians stress that they lack their own currency and control of their borders, imports and the roads between their cities. Fully 70 percent of those Palestinians are under 30. Their heroes are less likely to be the anticolonial Algerian revolutionaries their elders admired and more likely to be the demonstrators of Tunis and of Cairo’s Tahrir Square, who overturned Arab regimes. The change has to make Palestinian leaders anxious.

The standard explanation of why 20 years of bilateral peace talks have not produced an accord is that the differences on Jerusalem, refugees and borders are too wide to bridge. Israelis and Palestinian officials usually add that the other side is unwilling to make the essential concessions. This neat description ignores how the gaps shrank in years of negotiating, from Oslo through Camp David to the 2006 to 2008 talks between then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and Abbas. Not by coincidence, those talks stalled after corruption allegations forced Olmert to tender his resignation, making him a lame duck.

Netanyahu’s public position is that he is willing to negotiate. Less publicly, cabinet members cite the Standard Theory of Unbridgeable Gaps. Israel would prefer not to rule the Palestinians, but if need be can continue doing so, Ya’alon said. For Abbas, the status quo signifies failure. So he has turned to the United Nations.

It is a wild gamble. No one knows what effect a vote recognizing Palestinian statehood will have. Security Council approval is needed to accept Palestine as a member of the United Nations or to pass a measure requiring Israel to withdraw. But an American veto is certain in the Security Council. So a resolution recognizing Palestine can only pass in the General Assembly and would, under United Nations rules, be a mere recommendation: full of sound and fury, obligating no one. The day after the vote, Israel would not pull out of the West Bank, stop construction in Efrat or remove the roadblock between Ramallah and East Jerusalem. Palestinian security would likely continue coordinating antiterror work with Israelis.

So why seek recognition? Sweilem argued that after the United Nations decision sets the pre-1967 Green Line as Palestine’s border, future negotiations “will no longer be on the size of the state but on the mechanism of establishing it.” Israel could no longer use the amount of land it is willing to give up as a bargaining chip; at most, it could dicker about swapping pieces of land on either side of the border. But that is not much of a loss; the Olmert-Abbas talks already made the Green Line the basis for negotiations, and the remaining border arguments had narrowed to particular land trades.

If the resolution has an impact, it will mainly be as an “inconvenience” in international perceptions, argued Avi Primor, Israel’s former ambassador to the European Union. Israel, he suggests, will be regarded as occupying a sovereign state, rather than disputed territory. The image damage “could lead to more sanctions,” Primor said. But the effect will depend on the extent to which Western countries support recognition of Palestine. Those are the countries Israel is most dependent on economically “and…psychologically,” he said.

Indeed, Primor said, the Palestinian Authority faces a real risk that the resolution will do nothing. A likely result, he said, could be a new uprising that would start, at least, in the nonviolent “Mahatma Gandhi style.” But Palestinian leaders opposed to a new round of violence could lose control and the uprising could be aimed as much at the failed authority leadership as at Israel. Therefore, Primor said, it is possible that Abbas will accept any “real or fictitious” concession as a pretext for calling off the request for a United Nations vote.

So far, Israeli diplomatic efforts have been aimed at reducing the size of the pro-Palestinian majority in the General Assembly, particularly at swaying European governments. Primor’s analysis suggests that Netanyahu has a simpler way of avoiding the vote. He could endorse President Obama’s efforts to renew face-to-face Israeli-Palestinian negotiations grounded on the Obama parameters that “the borders of Israel and Palestine should be based on the 1967 lines with mutually agreed swaps.”

If the General Assembly does vote, an unpanicked Israeli response would be to celebrate recognition of Palestine as a political achievement for Israel. By recognizing Palestine as defined by the pre-1967 borders, the General Assembly would also be delineating Palestine’s maximum claims. The 1949 armistice lines would finally gain the status of international boundaries, which Israel has always lacked. Israel could and should argue that by recognizing Palestinian self-determination in the West Bank and Gaza, the United Nations has implied that Palestinian refugees should find their homes in the new state.

More sensible yet, Israel could preempt the Palestinian move by proposing to Washington that it drop its unqualified opposition to Security Council recognition of Palestine. Instead, the United States should submit its own resolution recognizing Palestine, explicitly stating that the borders could be adjusted by land swaps, and specifying that the Jewish and Palestinian states would each be responsible for repatriating members of their respective nationalities who lost homes in 1948.

In short, the September vote could signal the start of a new uprising, or a diplomatic setback for Israel—or an opening that Israel can seize for its own benefit. It is a gamble for the Palestinians as well as Israel, an international game of chicken. Netanyahu could avoid that gamble if he wants to complete the peace process rather than explaining why it can’t be done. Or he, like Abbas, could keep racing forward toward the collision.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply