Arts

Film

Brief Reviews: Images That Keep the Past Alive

Exhibits

Last Folio: A Photographic Journey With Yuri Dojc

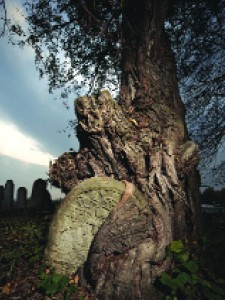

From Bardejov to Kosice, Lucenec to Michalovce, Slovakian-born photographer Yuri Dojc searched for his family’s past; Katya Krausova filmed his odyssey. Dojc’s haunting images capture a world of abandoned sacred objects, places and survivors. The camera finds beauty and color in decay, symmetry in disorder—the curling strip of a tefilin scroll on a cracked wooden table; books with peeling spines, their yellowing pages fanning out; details of beautiful frescoes in once magnificent synagogues. Remarkably, a gnarled tree has grown protectively over a headstone (right). The images of men and women, the Jewish remnant, bespeak both their suffering and dignity. At the Museum of Jewish Heritage–A Living Memorial to the Holocaust in New York, through late summer (www.mjhnyc.org). —Zelda Shluker

symmetry in disorder—the curling strip of a tefilin scroll on a cracked wooden table; books with peeling spines, their yellowing pages fanning out; details of beautiful frescoes in once magnificent synagogues. Remarkably, a gnarled tree has grown protectively over a headstone (right). The images of men and women, the Jewish remnant, bespeak both their suffering and dignity. At the Museum of Jewish Heritage–A Living Memorial to the Holocaust in New York, through late summer (www.mjhnyc.org). —Zelda Shluker

There Is a Mirror in My Heart: Reflections on a Righteous Grandfather

Suitcases filled with bread loaves, each inscribed with names; 30 ink drawings of superimposed signatures—these represent the thousands of Jews saved from the Nazis by Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the consul general in Bordeaux, France, who issued transit visas in 1940. These works as well as the writing of survivors names on 30 palimpsest drawings on paper is how Sebastian Mendes recounts his grandfather’s legacy. Through July 24 at Yeshiva University Museum in New York (www.yumuseum.org). —Sara Trappler Spielman

In Search of Biblical Lands: From Jerusalem to Jordan in 19th-Century Photography

When photography was introduced in 1839, pioneers of the medium flocked to the Holy Land, where they found dusty villages and a ramshackle Jerusalem. Yet the daguerreotypes and salted-paper prints of Bethlehem, Nazareth, Jaffa and Jerusalem, taken by French and British photographers between the 1840s and early 1900s, led to a boom in tourism and advanced the state of the art. Through September 1 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Pacific Palisades, California (www.getty.edu). —Tom Tugend

Charlotte Salomon: Life? Or Theatre?

At 23, Berlin-born Charlotte Salomon began her series of 1,300 small gouache paintings. Three years later, Salomon was murdered in Auschwitz. Resembling storyboards for a film and using strong lines and, often, dark colors, the 300 paintings and wall texts relate the life and love of a young woman given equally to depression and creativity. Through July 31 at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco (www.thecjm.org).

and, often, dark colors, the 300 paintings and wall texts relate the life and love of a young woman given equally to depression and creativity. Through July 31 at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco (www.thecjm.org).

—Renata Polt

Are We There Yet? A Thousand Years of Answering Questions With Questions

Artist Gil Gershoni and robotics professor Ken Goldberg’s media installation poses questions—some with Jewish themes (“What do Jews believe?”), some not (“Where is the restroom?”). Texts are projected on the walls and heard in various voices. Visitors can pose their own questions on an iPad. Answers? That’s up to you. Until July 31 at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco (www.thecjm.org). —R.P.

DVD

Yolande: An Unsung Heroine

Although Egyptian Jew Yolande Gabai de Botton (née Harmor) risked her life and that of her son to smuggle Arab League battle plans into Palestine at David Ben-Gurion’s request, the Sefardic spy died largely unloved and unrecognized by the new Israeli state. Elegant, beautiful, sophisticated—Levantine in every way—she glittered amid the higher circles of Egyptian government, completely in her element. When she made aliya, however, after being imprisoned in an Egyptian jail for passing Arab state secrets, she found herself a fish out of water. Like the last scene of a disturbing fairy tale, her end points to dark forces below. Directed by Dan Wolman and produced by Miel de Botton Aynsley (www.wolmandan.com). —Judith Gelman Myers

Web Sighting

Raising children brings up many questions, and for those with a Jewish family, the issues—teaching traditions, passing on values—may be even more complicated. A new site, www.kveller.com, from the creators of MyJewishLearning.com, aims to, if not resolve, then open up discussion about Jewish child rearing in the early years. Packed with information geared to today’s families, whether intermarried, gay or with two working parents, it includes a baby-name finder, a section on grandparents and articles on topics from being an over-40 first-time mother to talking about the Holocaust with kids. And there is even a Celebrity Q&A section for those who want to know about the “Top 20 Most Stylish Jewish Mommies in History” or advice from famous Jewish parents such as Mayim Bialik. —Leah F. Finkelshteyn

Films

The Gift to Stalin

This tragic film captures the troubled lives of political prisoners exiled in a Kazakh village under Soviet rule post- World War II. Sashka, a young Jewish boy from Moscow, is rescued by a railroad worker. He hides among villagers, forming friendships with caring adults and troubled youth from different nationalities. His surrogate grandfather sends him to safety before the anticipated gift for Stalin’s 70th birthday explodes. Aldongar Productions (www.silversaltpr.com). —S.T.S.

worker. He hides among villagers, forming friendships with caring adults and troubled youth from different nationalities. His surrogate grandfather sends him to safety before the anticipated gift for Stalin’s 70th birthday explodes. Aldongar Productions (www.silversaltpr.com). —S.T.S.

Jubanos: The Jews of Cuba

Brazilian-born American director Milos Silber’s 40-minute documentary shows the lives of Cuba’s remaining Jews. With assistance from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the Canadian Jewish Congress, community members celebrate the Jewish holidays in one of Havana’s three synagogues or in rural homes, managing to revive beliefs and traditions that were almost lost. Unfortunately, the film lacks any account of pre-1959 Jewish history. Ruth Diskin Films (www.ruthfilms.com). —R.P.

The Roundup (La Rafle)

On June 16, 1942, French police enthusiastically rounded up Jewish men, women and children, incarcerated them in the velodrome in the center of Paris for three days, then sent them by French rail to assorted concentration camps. The day has come to be known as the Vel d’Hiv, and it recently became the subject of a moving feature film called La Rafle (The Roundup). Author and director Rose Bosch, formerly an investigative journalist, spent two and a half years researching the Vel d’Hiv, and she included in her script many of the stories she uncovered in her research.

One of these was the story of Captain Henri Pierret. As head of the Fire Department, Pierret was ordered to appear at the velodrome on June 16, though he didn’t know why. He was surprised to find it cordoned off by scores of French riot police and an unidentifiable, but sinister, battalion of shadowy men in raincoats and hats. He passed through without incident, but when he entered the stadium he was greeted with the sight of 13,000 of his countrymen suffocating in the stifling heat, deprived of water for drinking, bathing and sanitation. Some had typhoid—French policemen eager to exceed the quotas set by the Nazis had grabbed them from the hospitals where they were being treated.

Pierret was outraged by what he saw, and he ordered his firefighters to uncoil the water hoses in order to supply the captives with desperately needed water. A lieutenant from the riot police immediately ordered him to fold the hoses back up. According to one firefighter who was there that morning, Pierret responded, with quiet fury, “In the absence of my superiors, I am in charge of fire safety here, and I am ordering you to step back and leave.” The lieutenant did as he was told, and Pierret demanded that the hoses be turned on.

Pierret didn’t stop there. When he discovered that his firefighters had secretly collected thousands of hastily scribbled notes, promising to deliver them to the families of the incarcerated Jews, Pierret granted his men a one-day leave, along with subway tickets, so that they might safely mail the letters from outside Paris. For his bravery, Pierret received the French Legion of Honor in 1950.

A young Jewish Pole and mother of five, though undecorated, was certainly no less brave. (Her grandchildren requested that her name remain undisclosed.) Like many Jewish families that lived east of Montmartre, this young woman and her husband had come to Paris 20 years earlier from a shtetl in Poland. They lived on the fourth flour of a shabby building and shared the bathroom down the hall with other, similar families.

In the days preceding the roundup, it had been rumored that police would take only Jewish men, so this young woman agreed to remain in the apartment with the children while her husband went into hiding. When, on the morning of July 16, she was awakened at 4:00 a.m. by the sounds of police vans and brutal shouts of “Get up! Get out!” she realized the French police were coming for her and her children, too.

Calmly, she gathered her children and told them that she was jumping out the window. She then instructed them to follow her. Terrified, the children refused. She did a quick calculation: Assuming the police wouldn’t deport children without their parents, she said to the eldest, a girl, “When they come, ask if you can take your brothers and sisters to the bathroom—then run as fast as you can.” Once she knew that her daughter understood her instructions, she turned away and jumped, ready to sacrifice her life.

The children were screaming in horror when the police arrived. Somehow, the eldest managed to remember her mother’s instructions and got permission to take her siblings to the bathroom at the end of the hall. From there the children rushed down the stairs to safety. Friendly neighbors brought them to Assistance Publique, who placed them in orphanages, where they were given French names to hide their true identities. Their mother had been right; without a parent, they were not deported.

Astonishingly enough, this woman’s self-sacrifice cost her only two broken hips. She was whisked away to the hospital, where she was allowed to stay under the care of a brilliant orthopedic surgeon. A year later she could walk again, but to little good; she was put on the list for deportation. Once more, her orthopedic surgeon came to the rescue: A member of the Resistance, he helped her escape.

She hid for the remainder of the war, making her way back to her old apartment after liberation. Unlike nicer flats, which were usurped when their Jewish owners were deported, hers had remained empty. Alone, she settled in—and that’s when she received the greatest miracle of all. Each of her five children came home, to be reunited with the brave young mother who had jumped out the window to save their lives. Menemsha Films (www.menemshafilms.com). —Judith Gelman Myers

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply