Arts

Personality

Profile: David Broza

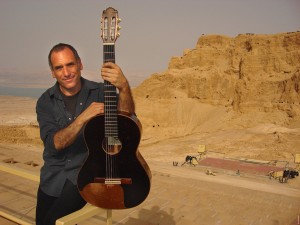

Photo courtesy of Shahar Azran/Polaris Images.

An ecstatic smile spreads across David Broza’s face. Onstage at New York’s 92 Street Y, he cradles his guitar against his chest, strumming quietly, his tender, gravelly voice caressing the Hebrew lyrics of Israeli poet Natan Alterman: “The day dies out/ a sunset lights up/ I walk in silence…. What more do I have? What more did I have?” The audience sings along, “Mutar lihyot sentimentali.” It’s O.K. to be sentimental.

Broza has walked in music and poetry since his first blockbuster, “Yihyeh Tov” (it will be good), hit the Israeli charts 34 years ago and became an anthem for peace.

His annual Christmas Eve concert at the Y is but a temporary anchor on his restless voyage as a troubadour of three cultures—Israeli, American and Spanish. He has moored his compositions to poetry, transforming the words of Yonatan Gefen, Walt Whitman, Federico Garcia Lorca and others into stirringly singable, beloved ballads. A masterful performer—he does 200 to 300 concerts a year, has released 32 albums in three languages and has been called the Bruce Springsteen of Israel—he shifts easily from chatting intimately with the audience to electrifying them with his guitar playing. “I’ll try to explain the songs,” he says, “but if I don’t, just assume it’s about love.”

Born in Haifa, raised in Tel Aviv, Madrid and England and a resident of Cresskill, New Jersey, from 1984 to 2001, Broza draws on his layered identity, seeking the melody within the lyrics and fusing Israeli pop, American rock ’n’ roll, folk and country and western, flamenco and Mediterranean music. “I’m coming out from the Israeli scene and trying to explore different influences that are so meaningful to me,” he says in a preconcert interview.

Outside of a strong israeli “t,” Broza’s American English is almost without accent. At 55, he is still a heartthrob: His graying, closely cropped hair with thin, curving sideburns draws his gap-toothed smile and chiseled features into relief. Off and onstage, he dresses in jeans and a black shirt.

He currently lives in the Tel Aviv home in which he grew up (his parents have passed away) with his youngest son, Adam, 21. “I travel so widely that coming back to my old neighborhood is almost a sacred experience,” he says. “I haven’t changed the house at all. The same art is on the walls. I am cooking on the same stove and eating on the same plates. The garden is the same garden my mother planted…. It is all very familiar and cozy.”

Broza is an endless traveler. Visiting a place is not enough for him, he has to immerse himself in its culture. The quickest and easiest way to do that, he says, is to read its poets. Living in a digital age doesn’t daunt him from urging others to seek out poetry: He has even created a Web series, Poetry from the Bench, in which he reads poems from the bench in his own garden. He plans to share music, art and more poetry from benches around the world.

Digital or literary, connections are vital to Broza. He places an American cellphone and Israeli BlackBerry side by side on the café table. “Whoops,” he says as one phone beeps. “Hold on. I’m controlling my life here.” It is his 30-year-old daughter, Moran, a chef, texting him that she’s watching him on television. Later, his son Ramon, 28, a stage production manager, texts as well. Both live in Tel Aviv.

Broza attributes his commitment to family to his parents, Sharona Aron, one of Israel’s first folk singers, and British-born Arthur Broza, a businessman and philanthropist. Though there is no official family connection, he traces his ancestry to the Spanish village of Brozas, which had a large Jewish population until the Inquisition. “Estuve Aqui” (I was here), from his Spanish album, Parking Completo, expresses his feelings as he walked the streets of the village on a visit in 1997.

From his maternal grandfather, Major Wellesley Aron, he learned the values of tolerance and coexistence. Aron was Chaim Weizmann’s political secretary, cofounder of the Zionist youth organization Habonim and founder of the Arab-Israeli settlement Neve Shalom–Wahat al-Salaam near Latrun. “My grandfather was one of the most uncelebrated heroes of the evolution and rebirth of the Jewish nation,” says Broza, a peace activist himself, a founder of Peace Now and a supporter of Neve Shalom. “Conflict resolution is a major issue that needs to be taught and passed on.”

“We are very proud to count him as a true friend who has always been willing to give of his time and talent on behalf of our community,” says Howard Shippin, a spokesperson for Neve Shalom–Wahat al-Salaam. King Juan Carlos of Spain even bestowed on Broza the honorary title of Ilustrisimo Don (the equivalent of Sir) for his music and efforts toward peace.

Broza also raises funds for the rehabilitation of the city of Lod. “I’m totally committed to making Israel a great place,” he says. In fact, he devotes a third of his time to humanitarian causes. Following in the footsteps of his father, a founder of the Spivak Sport Center for the disabled in Ramat Gan, Broza speaks out on behalf of the handicapped and raises funds for Spivak as well as the Nalaga’at Center in Jaffa, home to a deaf-blind acting ensemble and a café and restaurant. He recalls that from the age of 7, he, his sister, Talia, and their friends spent afternoons helping the handicapped adults and children at Spivak.

That experience reinforced his own courage when, in 1998, he was partly paralyzed in a car accident. The nerves in his left arm were damaged; five surgeons said he would never play the guitar again, but a sixth said Broza would know in a year if the nerves would repair. During that time, Broza strengthened his skills as a vocalist. “On the 333rd day, I felt something in my arm and I knew the nerves were reconnecting,” he says.

“Stuff happens,” Broza notes with equanimity. “Crippled or not I had to continue to be positive or I would fall into the deep hole of self-pity and misery, which is not even a choice.” He turns philosophical. “There can’t be any good without evil and evil can’t exist without good. I’m lucky I can go between the drops and try to stay away from the evil…. We’re in a state of war in Israel. It surrounds you but can’t bring you down. So I unroll my sleeves and go play. I look evil in the eye and say, ‘This is what I gotta tell you.’ And I sing ‘Yihyeh Tov.’”

Yonatan Gefen, his first writing partner (“Yihyeh Tov”) and one of his heroes, changed the direction of Broza’s life by encouraging him to view music writing as a responsibility. American poet Liam Rector introduced Broza to many American poets whose works Broza later set to music and recorded in five albums (Away from Home, Time of Trains, Second Street,Stonedoors, and Night Dawn

). Rector, who was director of writing at Bennington College in Vermont before he committed suicide in 2007, asked Broza to teach master classes there—which he did for 10 years.

“David is open, warm, smart, hard-working and extremely caring,” says Itzik Becher, who has known Broza for 20 years and heads Aviv Productions, the arts and entertainment agency that represents the singer. “Probably the best example of how much he cares is that he simply cancelled everything he had planned when the Second Lebanon War started. He went up north to sing and be with the people of Kiryat Shmona who were in shelters.” Becher calls Broza “one of the greatest guitarists alive. To Israeli music he was probably the first true folk-rock musician. To world music he is a bridge between three totally different worlds.” Broza plays a handmade Manuel Contreras classical guitar.

Broza’s family relocated to Spain when he was 12. From there, he was sent to Carmel College, a religious boarding school outside London. “I didn’t quite fit in,” he notes. “I was very artistic and didn’t care about praying three times a day. I wanted to do my own thing. So I wasn’t invited back.” Today, he belongs to Kehilat Sinai, a Masorti synagogue in Tel Aviv.

But Broza never envisioned music as a career. At 17, he was selling his paintings in the Rastro, Madrid’s flea market, and planning a future as a graphic designer. A year later, he volunteered for a three-year stint in the Israel Defense Forces and started playing at night in bars and cafés. He joined the IDF’s entertainment corps for the rest of his service—but still didn’t think of pursuing music full-time, until Gefen’s direction and the success of “Yihyeh Tov.” His sister, Talia Broza Liram, who often sang with him, lives in Jerusalem and was a producer of Israel tours.

Broza’s 1984 quadruple-platinum album, Ha-Isha Sheiti (the woman by my side), cemented his fame in Israel. Three times a year, he plays to an audience of 2,500 from midnight to 3 A.M. at the amphitheater at Masada. A PBS special, Masada: The Sunrise Concert, profiled Broza accompanied by rocker Jackson Browne and Grammy winner Shawn Colvin.

“I live to play and I play to live,” he says. “I do things on an impulse, but a very well-contemplated impulse.” He has no pre-show rituals. “I just concentrate. I contemplate it all day down to the details but that doesn’t mean it works out at all as you thought, so you adjust as you go.”

Broza’s latest projects reflect his far-ranging interests. Last year, he released Night Dawn:Unpublished Poetry of Townes Van Zandt

Broza’s latest projects reflect his far-ranging interests. Last year, he released Night Dawn:Unpublished Poetry of Townes Van Zandt . He met the American country-folk singer-songwriter only twice, but they shared a common passion for telling stories through music. They promised to meet again, but Van Zandt passed away in 1997. To Broza’s shock, Van Zandt left him 20 unpublished poems. Van Zandt’s widow, Jeanene, requested that he allow her to approach better-known American artists to see if they were interested in the project. After eight years, Broza found out nothing had transpired. Four days later, he received the poems by e-mail—and spent the next four years composing the music.

His next all-Hebrew album also breaks new ground, artistically and logistically. He is writing the lyrics himself for the first time and has launched the project through www.kickstarter.com, a Web site that enables artists to raise money for their endeavors from individual backers. This summer, he will perform his songs with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and with the Israeli Andalusian Orchestra, and he is preparing a book of all his music with stories and comments.

Offstage, he says, he is “your normal neighbor. I care for my family and my close friends. I’m not an all-out bohemian.” Five years ago, he and his wife, Ruti, divorced, and he is currently seeing New York-based fashion designer Nili Lotan. He spends much of his time writing.

Broza has accomplished his goal of creating his own cultural treasure on parallel tracks in three languages. “I’m waiting to see what will come next. I’m open,” he says. “I’m not walking on the same tracks I did before no matter what happens.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply