Arts

Exhibit

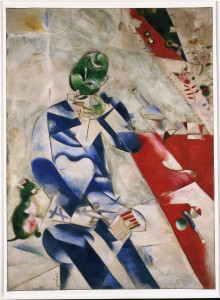

Chagall Through a Window

Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

An enlarged map of Paris from a 1920 French guidebook hangs at the entrance of the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s “Paris Through the Window: Marc Chagall and His Circle.” Focusing predominantly on the paintings Chagall made between 1910 and 1920, it includes works of several other émigré artists—many of them East European Jews—who made their way to the City of Lights at the beginning of the last century in search of culture, modernity and artistic freedom.

Stars on the map designate important locations in the life of Chagall (born in Vitebsk, Russia, as Moyshe Shagal), including his apartment/studio in the La Ruche (beehive) complex. Chagall and his colleagues formed what became known as the School of Paris, blending their own traditions with those of Cubism—which broke up objects and reassembled them in abstract forms, causing spatial ambiguities.

The exhibit’s 70 paintings, sculptures and works on paper illustrate the varied ways in which artists married their own traditionalism to what was then the predominant avant-garde movement and Chagall’s changing styles. Jacques Lifshitz’s sculpture Sailor with a Guitar is both realistic and Cubistically angular. Ossip Zadkine’s The Holy Woman shows a Byzantine influence; a fetus is visible through her womb.

Max Jacoby harkens back to mythological themes in his oil painting Orpheus Attacked by Brigands, while Moise Kagan’sKneeling Woman has a classicist touch.

Jules Pascin (born Julius Mordecai Pincas) uses neo-Impressionist style in his oil portrait of his wife, while Amedeo Modigliani’s elongated face in Blue Eyes is reminiscent of the Italian Renaissance and African sculpture. Born Ludwig Markus, Louis Marcoussis’s Portrait of Guillaume reflects his allegiance to Cubism.

Also represented are Chana Orloff, the only woman artist in the exhibit, through her sculpture The Dancers; and the oil paintings Woman in Red and Girl in Green by Chaim Soutine. Vivid theatrical colors are the hallmark of Leon Bakst (born Lev Samoilovich Rosenberg) who designed costumes and sets for the Ballets Russes and was a major influence on Chagall.

In the 1913 masterpiece that gives the exhibit its name, Chagall’s eye looks toward the Eiffel Tower from his studio in Montparnasse. The view is purely imaginative, since the artist was unable to see the landmark from there. The rectangular multicolored patches of sky are Cubist-like, and many elements are fanciful: A daredevil parachuting off the tower; a sphinx-like cat; upside-down train; and the figures of a man and a woman either lying or floating on their sides.

Philadelphia Museum of Art

In Half-Past Three, another large canvas, Chagall plays tribute to a poet friend, which morphs into a tribute to art itself. The figure’s head is upside-down, a takeoff on the Yiddish expression fardreiter kop (turned head). He is drinking a cup of coffee, but a bottle of wine hovers nearby, a source of inspiration. Chagall is apparently depicting the head-spinning impact of Cubism but also the giddiness bordering on madness that art and poetry induce.

Chagall’s gouache and watercolor To My Betrothed offers a kind of beauty-and-beast motif, as a brightly dressed minotaur-like figure embraces a woman. More seriously, his Smolensk Newspaper of 1914 (oil and graphite on paper) indicates the artist’s response to World War I, which found him back in Russia. As they read the headline declaring “war,” a young man reacts in horror and disbelief, while his older companion appears more resigned.

Included in the exhibit are some murals Chagall painted for the Petrograd Jewish Society after he and his wife, Bella, returned to the city in 1915 and he began to develop a faux-naif style that replaced both naturalism and Cubism. In Purim, large figures with gift baskets rush forward to observe the mitzva of mishloah manot. In Over Vitebsk, a Fiddler on the Roof-type beggar floats over snow-covered houses, suggesting a dreamlike quality.

The artist blends Jewish and Christian symbolism in such works as The Resurrection of a Lazarus, in which a Magen Davidand hands in a priestly blessing are engraved on the tomb of a Christian figure. The Crucifixion, which expresses Chagall’s distress over the plight of the Jews in Europe in the 1930s, substitutes the loincloth of Jesus with a talit.

Chagall’s droll humor and fanciful use of animals is evident in an oil painting from 1923, The Watering Trough. In the piece, a woman tries to prevent a trough from tipping over, while a pig observes the happenings with a sly look.

The exhibit may underscore artistic cross-fertilization, but also ambivalence, a different take on “I am in the West, but my heart is in the East.” InParis Through the Window, Chagall gives the artist two heads, looking in opposite directions. He was apparently torn between two worlds—his artistic soul nourished by Paris but his other half looking toward his East European Jewish roots and his wife. Even after fleeing Paris in 1941 because of Nazism and World War II, Chagall returned five years later.

“Trained in Vitebsk and St. Petersburg, Chagall changed his style of painting upon his arrival to Paris in May 1911, when he encountered Cubism and befriended many Cubist artists,” says John Vick, exhibition assistant for Modern and Contemporary Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. “That style further changed when he returned to Russia during World War I and the Russian Revolution, and then again when he came back to Paris in the early 1920s and began making prints alongside his paintings.”

What made the School of Paris unique was that it marked the first time a “group of modern, avant-garde artists rallied together not for the sake of a single shared artistic vision but a shared identity and experiences,” Vick adds. “That spirit of community was a vital part of who these artists were.”

“Paris Through the Window: Marc Chagall and his Circle” continues through July 1 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Perelman Building (215-763-8100; www.philamuseum.org). Several public lectures, performances and classes accompany the exhibit, which is presented in conjunction with the Philadelphia International Festival of the Arts, April 7 to May 1 (www.pifa.org).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply