Being Jewish

Feature

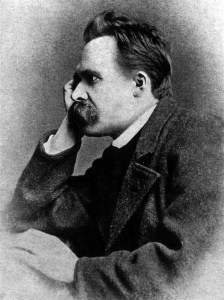

Letter From Herzliya: Nietzsche Revisited

No serious thinker has done more harm to the Jewish people than Friedrich Nietzsche. Born in Prussia in 1844, Nietzsche died in 1900; his writings were an important inspiration for Adolf Hitler and Nazism. Yet far from being an anti-Semite, Nietzsche was one of the most pro-Jewish German writers of his time. How can this paradox be explained and does it have any lessons for the present day?

No serious thinker has done more harm to the Jewish people than Friedrich Nietzsche. Born in Prussia in 1844, Nietzsche died in 1900; his writings were an important inspiration for Adolf Hitler and Nazism. Yet far from being an anti-Semite, Nietzsche was one of the most pro-Jewish German writers of his time. How can this paradox be explained and does it have any lessons for the present day?

Nietzsche was the son and grandson of Lutheran ministers. He became an academic expert on ancient Greece, yet his poor health forced him to resign his professorship at a young age.

He spent most of the rest of his life on a pension, traveling from spa to resort town trying to avoid the extremes of weather that gave him such physical discomfort.

A massively productive and self-consciously iconoclastic writer, Nietzsche never attained a large readership in his lifetime, though his fame did grow. His life and works are too complex to summarize here but one constant feature of his worldview was his friendliness, even admiration, toward Jews.

The growing anti-Semitism in Germany during the 1870s and 1880s disgusted him. He derided the hatred of Jews by the composer Richard Wagner, a friend with whom he eventually broke, and he tried to block his sister’s marriage to an anti-Semitic agitator. Nietzsche had several Jewish friends, including one of his greatest admirers, the famous Danish literary critic Georg Brandes. After a stimulating conversation with another Jewish friend, Helen Zimmern, Nietzsche noted, “It is fantastic to what extent this race now has the ‘intellectuality’ of Europe in its hands.” His biographer, Curtis Cate (Friedrich Nietzsche, Overlook Press), accurately calls Nietzsche an “anti-anti-Semite.”

Moreover, though he is mainly remembered for his concept of the “Ubermensch” and “the splendid blond beast”—as he called the aristocratic predators who write society’s laws—Nietzsche was an antimilitarist. He hated the German monarchy and loved France (at that time, Germany’s main enemy), Switzerland and Italy, where he spent most of his adult life. Far from believing in the superiority of the Aryans, he liked to imagine he himself had Polish ancestry.

To give a sense of Nietzsche’s worldview—though these extreme sentiments came after 1888 as he began to descend into madness—Nietzsche urged the rest of Europe to unite against Germany, called on Jews to help him in his campaign against Christianity and said he would like to kill all the German anti-Semites.

There is no doubt that if he had lived to see Nazism he would have been appalled and outspoken in his enmity, though his sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, became an enthusiastic Nazi; when she died in 1935, Hitler himself attended her funeral.

How then did this pro-Jewish philosopher become an inspiration for the murderers of 86 percent of Europe’s Jews? So much so that his works became official Nazi doctrine and the dictator ordered that a monument be built to honor him?

The immediate answer is Nietzsche’s hatred of Christianity and belief that a post-Christian, secular morality must be developed. In this regard, he was part of the post-Darwin reaction to the cracking of religious certainty. As a believer in what Brandes called “aristocratic radicalism” and having a horror of democracy, Nietzsche, in the words of Cate, contrasted “the positive ‘breeding’ of aristocracies to the negative ‘taming,’ ‘castration’ and emasculation of the strong by insidious ‘underdogs.’” Or in Nietzsche’s own words:

Christianity, growing from Jewish roots and comprehensible only as a product of this soil, represents a reaction against the morality of breeding, of race, of privilege—it is the anti-Aryan religion par excellence.

In his book Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche penned what became the core of Nazi philosophy and the death knell for European Jewry:

All that has been done on earth against ‘the nobles,’ the ‘mighty,’ the ‘overlords’…is as nothing compared to what the Jews did against them: the Jews, that priestly people who were only able to obtain satisfaction against their enemies and conquerors through a radical revaluation of the latter’s values, that is, by an act of the most spiritual revenge…. It was the Jews who…dared to invert the aristocratic value-equation…saying ‘the wretched alone are the good ones, the poor, the helpless, the lowly…. You who are powerful and noble are to all eternity the evil ones….’

This was, however, in contrast to what the Nazis made out of it later and the Islamists do today. Nietzsche didn’t accuse the Jews of doing anything on their own—no conspiracy of the Elders of Zion—but merely the “invention” of Christianity. What should be stressed here is that his diatribe against Jews was a small, isolated part of his writing that did not otherwise carry over into his life or thinking. It was his sister who helped pervert her brother’s thinking when she grafted her anti-Semitic, nationalist ideas onto his philosophy in the book The Will to Power.

Nietzsche dissociated the existing Jews from the harm he perceived arising from those Jews—especially Paul—who had created Christianity two millennia earlier. Nietzsche used these terms interchangeably when he said the “Western world was now suffering from ‘blood poisoning’” through being Jewified, Christianized or “mobified.”

But earlier, he had written admiringly in explaining his opposition to anti-Semitism: “The Jews, however, are beyond all doubt the strongest, toughest and purest race now living in Europe.”

Indeed, they fit his aristocratic prescription since they survived “thanks above all to a resolute faith that does not need to feel ashamed in the presence of ‘modern ideas.’”

Germany, he continued, would do better to deport the anti-Semites than the Jews who would provide many good qualities.

There are three interrelated answers to how Nietzsche became, in effect, the unintentional intellectual executioner of European Jewry and in the way all too many modern intellectuals resemble him.

The first is that he dragged the Jews into his broader program of tearing down Christianity, making them props for his current agenda.

In Nietzsche’s time, most anti-Semites hated Jews; they saw Jews as symbols of modernity, socialism and opponents of nationalism.

Today, Western leftist professors, intellectuals and journalists have simply turned this process on its head: same attack but for the exact opposite reasons. Now they attack the Jews—at least those who do not accept the doffing of their identity as a people or their strong religious belief—and their main contemporary product, Israel, as symbols of all the things that are part of their campaign against Western civilization, traditional viewpoints, nationalism and capitalism.

They are prepared, too, to admire Jews, on condition that they become—in the phrase of Isaac Deutscher, a Jewish Marxist writer and political activist—“non-Jewish Jews” who put the cause of revolution first and their own people’s interests last.

On the previous occasion that this happened, it led young Jewish Bolsheviks to work enthusiastically to destroy Jewish religion, culture and identity in the former Soviet Union, until the dictatorship they built up dispensed with them as well.

Second, the promoters play with ideas and ideological systems without comprehending how these career-making, attention-getting games have poisonous consequences. Already, the small remnant of Jews in Europe who survived the Nazis is feeling the pressure from Islamists, leftist ideologues and more traditional right-wing haters, and their departure from their countries of origin is no longer beyond possibility.

Third, like Nietzsche, they don’t realize how their sophisticated arguments can affect the unsophisticated. These journalists and professors refuse to recognize how the nuances of their lectures, plays and newspaper articles become sledgehammers in the hands of militant activists.

Like Nietzsche, they play with the issue of Jewishness without realizing they are laying the foundation for far more violent and vicious assaults, notably, but not exclusively, that of the genocide-oriented Islamists.

Unlike Nietzsche, however, they make things even worse by denying or minimizing the threat of the Islamists, the dangerous anti-Jewish forces of our era.

Yet Nietzsche was also superior to these modern ideologues (and it is possible to feel far more sympathy for him than for them). After all, he consciously and explicitly decried totalitarian politics and upheld free thought against hegemonic dogma.

Thus, our modern “Nietzsches,” some Jewish themselves, are repeating this sad history, which might—though we hope not—also end in rivers of blood.

We should all remember the terrible irony that the man who wrote “Heaven have mercy on European understanding, if ever one wanted to remove from it Jewish intelligence” was the philosophical architect of that very deed.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply