Wider World

Feature

Honoring Our Ancestors

Dan Ben-Canaan

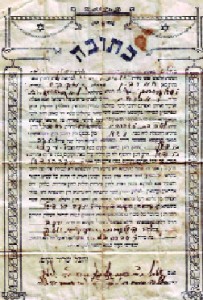

Dan Ben-Canaan slowly lifts the rumpled, yellowed sheet of paper and shows it to his audience. A professor of research and writing methodology at Heilongjiang University’s School of Western Studies, he is displaying a new acquisition: a 100-year-old ketuba. The people before him are visiting Jewish history buffs, gathered in a room at the Heilongjiang Provincial Academy of Social Sciences.

The Israeli-born Ben-Canaan had received the ketuba a few days earlier, part of his duties as founder and director of the Sino-Israel Research and Study Center at the university, located in the city of Harbin in northeast China. It belonged to the parents of Zena Dann, 87, who had traveled from Australia for a visit to Harbin, where she was born and raised.

Dann’s parents were among the entrepreneurial-minded Russian Jews who, 100 years ago, came to frigid Harbin, then a special zone under Russian control inside Manchuria. These immigrants turned the city into the largest Jewish cultural and economic center in the Far East; its Jewish population peaked in the 1920s at about 25,000. Political upheavals in both Russia and China forced most to flee by the 1950s, but over the past decade, and with the help of the municipality, Harbin is reclaiming its Jewish past.

Opened in 2002, the Sino-Israel center’s staff of about a dozen, including postgraduate students and research assistants, collect memorabilia. They are also compiling an inventory of buildings once owned or built by Jews.

Charles Berelowitz

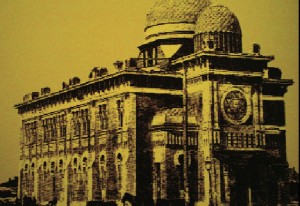

One of the center’s first tasks was to set up a museum to tell the story of the thriving Jewish community. Inaugurated in January 2006, the Jewish Museum of History and Culture is housed in the New Synagogue, completed in 1921, at 162 Jingwei Street in the Daoli district. The city has restored the stately New Synagogue—where Dann’s parents were married—and the 103-year-old Main Synagogue, which now houses a Montessori school, with funding from the Chinese regional government.

Dioramas, photos, paintings and videos of business and family vividly re-create daily life during the heyday of Jewish prosperity between the two world wars. Much of the museum’s collection comes directly from descendents like Dann—she also gave Ben-Canaan stacks of black-and-white photographs plucked from a family album—who are sending materials from around the world, particularly from the United States, Canada and Israel.

The current passion for genealogy has become the motivating force for this generation. One impact has come from the Harbin pages on the Jewishgen Web site (www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/harbin/index.htm), hosted by Irene Clurman, a descendent of Harbin Jews who lives in Evergreen, Colorado. “When [people] find out they had an ancestor who came from Harbin,” said Clurman, “they become fascinated with the history and look for more on the Web. We give them a sense of what life was like from our old letters and photos.” The images and information often pique their interest in this exotic and improbable place; some even travel to see it for themselves.

Charles Berelowitz

In Harbin’s old Jewish neighborhood, Pristan, part of the city’s downtown business district, wrought-iron lampposts along Tong Jiang Street are now topped with Magen Davids. A plethora of long-neglected Jewish villas and majestic communal buildings have been given face-lifts.

Jewish influence is partially responsible for Harbin’s Western appearance today. Public buildings constructed by Jews were a flamboyant mix of European and Moorish architectural styles. Most were built of brick with reinforced concrete and painted red and white, with high arched windows, roof decorations and massive supporting columns.

Among the buildings with a Jewish past is the Hotel Moderne at 89 Zhongyang Street in Daoli. Still open for overnight guests, the hotel used to host Jewish community events. A plaque outside describes its history: The three-story Art Nouveau-inspired building was built in 1906 by Joseph Kapse, a Jewish businessman, and was considered the most glamorous hotel in the area. Its old-fashioned paneled bar provides a window into 1920s Harbin: Walls are lined with aging photos of distinguished visitors, like the opera star Feodor Chaliapin. Dusty glass display cases are filled with quirky items—a silver samovar, a beer tap and an Underwood typewriter. The ambiance is reminiscent of aristocratic prerevolution Russia.

“This old architecture is just like a mellow wine,” said Li Shu Xiao, former deputy director of the Harbin Jewish Research Center, a separate government initiative attached to the Heilongjiang academy. He points out the hotel’s aristocratic grandeur, reflected in its ornate windows and elaborate flourishes reminiscent of French architecture from the period of Louis XIV. There is even an onion dome perched on the roof, which adds a certain Russian flair.

The municipal authorities have also constructed a Jewish chapel at the refurbished Jewish cemetery in the eastern suburb of Huangshan. It has become yet another key destination for the increasing number of Jewish tourists, many of whom come to pay their respects to their ancestors. Some 400 visitors arrive each year, according to Ben-Canaan.

Charles Berelowitz

Arguably the best-known tourist was former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, who came to Harbin in 2004 to unveil a new tombstone erected on his grandfather’s grave, following the restoration of the cemetery. Olmert had been visiting China as part of an Israeli business delegation and made a private detour to the cemetery. Other notable descendents include Lawrence H. Tribe, professor of constitutional law at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Robert Skidelsky, a member of the British House of Lords.

Highly visible is the restored architectural legacy of the many public buildings that reflect the classical European and Russian styles the Jews brought with them. “They prided themselves on being worldly,” observed Clurman. Thus, to walk the streets of downtown is to walk in a Russian or European city—a cornucopia of tall windows, sharply sloped roofs and onion domes. A total of $2.5 million of public funds have so far been spent on refurbishing Harbin’s Jewish sites, according to a 2006 article in the China Daily.

The Chinese authorities are candid about why they are spending time, money and effort on the Jewish heritage sites. On the positive side, they are genuinely respectful of Jewish achievements. Jews are particularly acknowledged for making Harbin a “city of music,” according to Qi Wei, president of the Heilongjiang academy, because they imported a strong musical tradition, perhaps as part of their assimilated Russian heritage. “The top-class Jewish artists often gave performances,” noted Qi Wei. “Many people took the Jewish artists as their tutors and soon became qualified in the field of music, too.”

“My grandmother talked about seeing a lot of operettas in Harbin,” recalled Clurman.

In addition, the Chinese unabashedly recognize the economic potential of linking to their Jewish past. A plaque at the entrance to the Jewish museum calls it “an opening to the outside world, a bridge promoting the friendly exchanges, and a highlight boosting…Harbin tourism.” The Harbin Jewish Research Center is aimed both at raising Harbin’s Jewish profile and fostering investment from the Jewish world.

Some, including Clurman and Ben-Canaan, suggest the goal of attracting Jewish investment is paramount. Indeed, “In the eyes of most Chinese, Jewish people are considered sufficiently ‘good at making money,’” noted a March 2010 article in the online newspaperThe European Union Times (www.eutimes.net). How-to books on making money like the Jews have become best sellers in China.

Still, why would the children and grandchildren of Harbin Jews care about this place? “In Harbin, Jews were free to do whatever they wanted,” said Archie Ossin of Alamonte Springs, Florida, whose family lived in Harbin. “There was no danger of pogroms. The Chinese were not like the Russians.” For many, therefore, Harbin remains a haven of sweet memories.

Yet, prior to the opening of China’s interior to international visitors in the 1970s, those memories had been fading fast. Moreover, the Jewish-Chinese connection was overshadowed by the larger Shanghai, recognized as a crucial haven during the Holocaust.

Set in the heartland of Manchuria, barely 400 miles from the Russian border, Harbin was originally a piece of Russia inside China, somewhat akin to British Hong Kong. It was sparsely populated, located in a remote region where Chinese territory pokes a long finger northward toward the icy lands of Siberia. In the winter, outdoor temperatures can drop to minus-30 degrees Fahrenheit, and by midafternoon, a dim sun casts long shadows before early darkness envelops the city. In spring, harsh winds from the Mongolian steppes pelt passersby with the fallout from dust storms that feel like a rain of tiny stones.

Still, in the late 19th century, imperial Russia needed to extend its Trans-Siberian Railroad farther eastward. The Chinese, worried about the expansionist rumblings of the Japanese, offered the Russians a land concession as a terminus for their railroad, in part as a bulwark against Japanese intentions. Finding adventurous people to populate and develop the inhospitable location was not easy.

Part of the solution was to offer enterprising Jews a chance to live in a place that would be free from the restrictions and brutality facing them inside Russia. Those Jews worldly enough to be aware of a potential bonanza in Manchuria’s untapped mineral and agricultural riches fled east rather than west. Among the first settlers were also Jewish soldiers, forcibly conscripted into the czar’s Army, sent to Harbin to fight the Japanese.

By the second decade of the 20th century, Harbin had become a boomtown. Jews built schools, hospitals, homes for the aged, banks, publishing houses, bakeries, pharmacies, synagogues, music conservatories, cultural centers and even a movie house. They opened stores, developed mines, sugar refineries, tobacco factories, processed timber and farmed fields of soybeans for export. Deals could be made in any currency. Photographs from 1905 to 1925 show cosmopolitan and assimilated Russian Jews.

Like their publications, the epitaphs on their gravestones are mostly in Russian, with a smattering of Hebrew. One monument proclaims that the deceased had earned a degree from the Petrograd Conservatory of Music—a status symbol in a community known for its classical music.

In the violent upheaval following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, more Jews arrived as well as displaced White Russians—aristocratic and privileged followers of the czar who tended to be rabidly anti-Semitic. They soon outnumbered the Jews two to one. They accused Jews of aiding and abetting the revolution. The local Chinese, always in the majority, tried to keep a lid on rivalries. And between the wars, the city, independently self-governing, became a hotbed of Zionist activity, outlawed inside the Soviet Union.

The Japanese occupation of Manchuria, starting in 1931, cast a further pall. Collaborating with the White Russian community, the Japanese preyed on the Jews, grabbing property, kidnapping Jews and ransoming them for large sums of money. Some Jews left, yet despite the drawbacks, others continued to arrive, viewing Harbin as a potential refuge during the Holocaust.

But the good times were over. When the Soviets returned at the end of World War II, many Jews were carted off to the gulags, accused of being Japanese spies. The final denouement came around 1946, when the Chinese Red Army marched in and confiscated whatever was left. Wealth, built over a lifetime, vanished in a day. By the 1950s, virtually all Jews had fled.

But if they were forced out of Harbin, they retained rose-tinted memories. Ben-Canaan is discovering that the brutal and terrifying years of the Japanese occupation and constant threats from White Russian neighbors are often glossed over. Yet, he noted, “I have found correspondence in Shanghai and Germany of Jews from Harbin buying weapons for self-defense.”

Another challenge has been the refusal of the Chinese authorities to open archives relating to Jewish business ownership, birth, death and marriage. No official reason has been given. Still, the general belief is that the authorities fear restitution claims. Lord Skidelsky, a descendent of one of the largest business- and land-owning Jewish families from Harbin, is among those who have filed a claim with officials on behalf of Skidelsky descendents. In 1984, he was offered $18,000, he reports, in full settlement for property that he insisted amounted to $8.1 million.

Others relate similar frustrations. “They gave us only around $12,000,” said Ossin, for real estate worth $40,000 in 1920. His grandfather had owned a downtown square block, with shops and residential rental properties.

Despite drawbacks, a strong sense of community still lingers among the descendents. Clurman’s Web pages, now three years old, helps Jews trace their Harbin ancestors. A bimonthly newsletter and magazine called Igud Yotzei Sin(www.jewsofchina.org), published in Israel by the Association of Former Residents of China and mailed worldwide, similarly updates history and keeps descendents in touch. Readers congratulate each other on simhas. They raise money for the needy. “It was always considered cool to come from Harbin,” said Clurman. “We were a very, very close community. There are probably only a few dozen [original residents still living].”

Hannah Agre, a musician and the last Jew living in Harbin, died in 1985, according to Li Shu Xiao. And five years ago, Warsaw-born Israel Epstein, who had spent part of his childhood in Harbin, died at the age of 91. A dedicated socialist, he rose rapidly in the Communist government and was given a state funeral in Beijing.

Of the permanent newcomers, there is, as yet, only Ben-Canaan. “Of course there is a community of Jews,” he quipped. “It’s me!”

Andrée Aelion Brooks can be reached at andreebrooks@hotmail.com or www.andreeaelionbrooks.com.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply