Arts

Exhibit

Museum Makeover

All images by Tim Hursely/Courtesy of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

The 16-foot hourglass of polished steel, reflecting an inverted sky and surrounding landscape, shines at the highest point of the grounds of the hilltop Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Commissioned in honor of the venerable institution’s three-year expansion and redesign, Turning the World Upside Down by Mumbai-born Anish Kapoor calls to crowds in the city and beyond to come view the extraordinary objects on display at the museum (011-972-2-670-8811; www.english.imjnet.org.il).

The $100 million project—which museum director James Snyder said at the reopening last July had been completed “on time and on budget”—aimed to create more exhibition space, make the layout more intuitive and increase accessibility. Visitors have a choice of how to traverse the uphill slope from the entrance pavilion to the galleries. They can take the open-air pathway—the original main approach—enjoying views of the city and guided by the Kapoor sculpture. Or, they can walk up a shorter, enclosed route that has a gentler incline with no steps, making it wheelchair accessible.

Both paths lead to the central pavilion from which the three main wings—archaeology, Jewish art and life and fine arts—branch out. Each of those wings has new galleries, enabling the museum to exhibit objects the public has never seen before. Three new galleries house temporary exhibitions, and there are now dairy and meat restaurants as well as cafés. And all these changes have been made without altering the museum’s famous skyline.

First opened in 1965 and designed by Al Mansfeld and Dora Gad, the museum consisted of unadorned white stone Modernist cubes hugging the hill and seemingly scattered like the houses of an Arab village. The design was considered so successful that, in 1966, Mansfeld and Gad received the Israel Prize, the country’s top honor. The museum is one of the great achievements of the city’s legendary mayor, Teddy Kollek, and it has always been a major attraction. Nearly 140,000 people visited in the first month after the reopening.

The original plan made it possible for the museum to grow organically through the addition of modular units when the collections grew—ultimately to 10 times the size. But that organic growth generated confusion; visitors got lost in the maze of exhibits.

“Our work is to ease people’s sense of where they are going,” said New York-based architect James Carpenter at the outset of the project. Carpenter created the redesign with Tel Aviv-based Efrat-Kowalsky Architects.

In providing a more intuitive layout and doubling the exhibition space to 200,000 square feet, the current designers wisely chose not to alter the original concept. They achieved this mainly by adding space underground. For example, Carpenter pointed out that below the new entrance pavilion, gift shop and restaurant at the front of the museum is a large, two-story structure that houses archival storage and kitchens. Similarly, the enclosed route of passage that leads to the new central pavilion passes under the original outdoor approach. And much of that central pavilion, built where a cafeteria once stood, is itself belowground.

Where the designers added construction aboveground, they kept it close in shape to the original cubes but used mainly glass, instead of stone, for the exterior. Louvers, some inside the glass and some outside, let natural light pour in and allow views of the landscape while protecting exhibits from the sun’s rays. Carpenter said that he was intent on retaining “the intimate relation of the museum with the landscape”—a hilly green swath dotted with olive trees and overlooking a fourth-century monastery.

The museum is actually three distinct parts, each representing a different strain of Modernist architecture. The main part, designed by Mansfeld and Gad, is the one that was expanded and redesigned. The Dead Sea Scrolls and other finds from the Judean Desert are housed in the second part, the Shrine of the Book, designed by architects Frederick Kiesler and Armand Phillip Bartos. It consists of a gleaming white dome shaped like the lid of the jars in which the scrolls were found, juxtaposed against a dramatic black wall.

In 2006, a scale model of Jerusalem from the late Second Temple period was installed next to the Shrine of the Book; it shows what the city looked like in 66 C.E.

The third major part of the Israel Museum is the Billy Rose Art Garden, designed by Isamo Noguchi. Set against the hills of Jerusalem, this garden, made up of crescent-shaped terraces, is home to sculptures by Auguste Rodin, Henry Moore, Menashe Kadishman and many others.

In honor of the expansion, the museum commissioned, in addition to the Kapoor sculpture, a 44-foot-wide rainbow of narrow painted panels representing the progression of colors in the spectrum visible to the human eye. That piece, by Olafur Eliasson, is at the top of the new main approach.

But interesting as these new works are, they are outclassed in evocative power and meaning by the slim, 36-inch-high sculpture that is the sole exhibit in the Cardo—the hall in the museum’s new central pavilion that connects the three main wings. This is Itzhak Danziger’s Nimrod, carved in soft red Nubian sandstone in 1938. In Near Eastern mythology, Nimrod is a figure with divine powers; in the Bible, he is the great-grandson of Noah, “a mighty hunter before the Lord.”

Danziger’s sleek image of this powerful hunter-warrior, with beastlike bulging eyes and sniffing nose, a hawk on his shoulder and a bow hidden behind his back, has aroused stronger responses than any other Israeli sculpture since it was first displayed at Tel Aviv’s Habima National Theater in 1944. Reviled by religious groups (partly because the talmudic literature portrays Nimrod as the rebellious idolater who built the Tower of Babel), the sculpture was embraced by a group of Israeli intellectuals and artists who saw it as a symbol of their identity, and it inspired others to use motifs from biblical stories and the art of the region’s ancient cultures.

This masterpiece seems to reflect the museum’s focus. Nimrod, a symbol of Israeli culture, was chosen for this spot because it is “resonant with meaning, in how things connect…[and because it] links the ancient and the Modernist,” Snyder said.

“Less is more”—the motto of the Modernists and the rationale behind the clean lines of the museum’s original buildings—is also the guiding principle behind the new structures and permanent exhibitions.

In the Jewish art and life wing, for example, visitors were often overwhelmed by the large number of objects. “Our experience is that you can’t see the objects if the showcase is full,” said Judaica curator Rachel Sarfati. Now, the focus is on prime objects that tell a story, such as a 20th-century bridal costume from Cochin, India. During the marriage ceremony, the bride would sit in the synagogue near the Ark, her head and the upper half of her body concealed by a canopy and only her skirt, richly embroidered with metallic thread, displayed.

An exception to the focus on individual objects is the gallery displaying 120 Hanukka lamps from around the world. Each appears in a separate window, as these lamps were traditionally shown and as they can be seen to this day in Jerusalem during the holiday.

“You feel the light. Here, more is more,” Sarfati said. “You feel as if you are walking in the street.”

Among the highlights is a lamp from Mazagan, Morocco, created around 1950 by Meir Ben Ami of cut tin, scraps of cloth and pieces of glass. Visible on the tin are the words “Sardines in olive oil.” Another 20th-century lamp is an unadorned wooden Star of David with small glass receptacles for oil. It comes from the Bene Israel community in Mumbai and was probably hung on the wall.

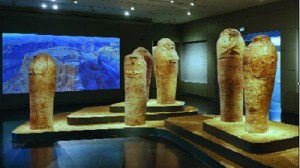

The museum has the world’s most extensive holdings of biblical and Holy Land archaeology, and in the archaeology wing, too, visitors may have been overwhelmed by the sheer number of exhibits. Now, they encounter the drama and mystery of ancient times at the very entrance, where seven human-shaped coffins from the 13th-century B.C.E. stand upright, hands folded over their chests. Some of their faces express serenity while others look as though death has caught them by surprise.

The exhibits in this wing tell the story of the region chronologically, from prehistory through the Ottoman Empire. The first gallery, devoted to prehistory, contains a shell necklace that is 14,500 to 30,000 years old. Nearby is a 28,000-year-old small stone plaque incised with a horse.

There is a ninth-century B.C.E. stone inscription in Aramaic from Tel Dan in northern Israel containing the first-known instance of the phrase Beit David, the House of David; it appears near words that refer to royalty.

Two shrines from the eighth to seventh centuries tell the story of the biblical prophets’ struggle to eradicate polytheism in favor of monotheism. One is a Judahite shrine from Arad, in southern Israel, a three-sided enclosure of rough stone with two altars made of squared blocks of smooth stone with no ornamentation. The other is an Edomite shrine from Hazeva, also in the south, which has votive figures in human shapes, perhaps representing the worshipers.

Hebrew writing, glass and coins receive special emphasis, but there are objects that offer a glimpse of everyday life: for example, pottery churns and food-storage vessels. Explanatory texts on adjoining panels have been reduced to a minimum, keeping the focus on the objects themselves.

Many of the exhibits are displayed without cases. Visitors can view side by side a composite church and a synagogue from the Byzantine period (fourth to seventh centuries C.E.) and see the similarities in their architecture while noting interesting contrasts. For instance, both have three arched niches in the front wall, but their functions are different.

An exception to the rule of open display is a life-size second-century C.E. statue of Aphrodite from a bathhouse in Beit Shean, in the north. Its glass case protects the traces of red, blue and gold paint on the sculpture, evidence that Greek and Roman statues were brightly painted.

Also in the archaeology wing, a new gallery is dedicated to the legendary pioneers of biblical archaeology. The display explores the research of Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, the first to identify tells—artificial hills—as the mounds of cities built one on top of the ruins of the other; and Conrad Schick, the first to measure, draw and describe Jerusalem’s ancient aqueducts.

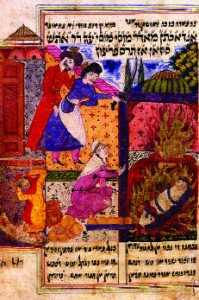

In the Jewish Art and Life wing, a gallery exhibits Hebrew illuminated manuscripts, two of which are being shown for the first time. One is Maimonides’s Mishne Torah, created in the 15th century with illuminations by one of the finest workshops of miniature painting in northern Italy. The page on display depicts the high priest of the Temple, in Renaissance dress, carrying out the sacrifices, including the burnt offering. Another illuminated manuscript is Musa Nama (Book of Moses), a poetic compilation of biblical books in Judeo-Persian. Created in Tabriz, Persia, in 1686, it has miniatures that reflect Muslim influence.

Exhibits related to Jewish festivals are now grouped by theme—the three festivals of pilgrimage: Pesah, Shavuot and Sukkot—and Israeli holidays have been added. A video by Yael Bartana shows automobiles stopping at the sound of the siren on the Memorial Day for Israel’s Fallen Soldiers and Terror Victims.

A restored sparkling white interior of a synagogue from Suriname has been added to the display of three from Germany, Italy and India. The Suriname sanctuary was built in 1736 by descendants of Spanish and Portuguese Jews who fled to Holland to escape the Inquisition; those descendants were among the early European settlers in Suriname, north of Brazil. Arched windows flood the interior with light, and sand on the floors is a reminder of the time when worshipers prayed in secret and had to muffle the sound of their steps. All the furnishings are original.

The Israeli section of the new fine-arts wing includes a video by Sigalit Landau, called DeadSee, in which a spiral of watermelons and the nude artist herself float in the Dead Sea—the spiral of fruit slowly unwinding.

The museum has added a gallery devoted to Dada, with works by Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, as well as one dedicated to Surrealist art that includes a 1964 work by Christo. Digital art now has its own gallery.

Many written texts are now in Arabic as well as English and Hebrew, and an Arabic audio guide is being prepared. The additions are part of a policy to make the museum accessible to a wide variety of people, according to Tali Gavish, head of the Ruth Youth Wing for Art Education. One of the outreach programs trains Arab teachers to use art in the classroom and the museum as a resource; another brings Arabic-speaking children to the museum for visits and activities.

The success of the expansion is no mean feat when compared with an earlier proposal. In 1999, the museum unveiled a plan by American architect James Ingo Freed. A donor who had pledged most of the cost had chosen Freed, lead designer of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. Freed’s plan included a 72-foot-high visitor center inspired by a Canaanite altar with four horns, which would have dwarfed the Shrine of the Book and required the destruction of part of the sculpture garden.

The plan aroused a public outcry, and Mansfeld submitted a formal objection to the Jerusalem District Planning Commission. Freed’s design was scrapped in 2002.

But the current redesign has critics, too. Many say it is still easy to get lost in the museum. Some claim the new enclosed passage route is more suited to an airport. Tour guide Jeff Abel complained about the dearth of practical elements, such as toilets and benches, though he praised the improved lighting in the fine-arts wing.

Edwin Heathcote, architecture and design critic for The Financial Times, praised the redesign, but also commented: “[Carpenter] has done a sophisticated job in seamlessly connecting the disparate elements of the museum, but…the new buildings…exhibit a kind of bland, commercial aesthetic. It is an intriguing trade-off for such a monumental site and Carpenter, perhaps wisely, has eschewed the opportunity for nation-building gestures.”

With the Knesset, the Supreme Court, the Hebrew University, the Science Museum and Bible Lands Museum grouped together on a series of hills, the Israel Museum stands for culture and reason in a city riven by religious and political strife. Like Kapoor’s new sculpture, it turns the city’s madness upside down.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply