Arts

Exhibit

A Jewish History Picture Show

(USA), Inc. All rights reserved.

In Uri Shulevitz’s autobiographical children’s book, How I Learned Geography, a young boy flies over a world bursting with color and populated by magical creatures and otherwordly landscapes. a Living far from the Warsaw home he and his parents fled in 1939, Shulevitz looked at the map his father hung in their tiny hovel in Turkistan and imagined a better universe.

Books and art in Jewish life have long offered both expression and escape, whether from the Nazi horrors or the challenges of assimilation. And it is into this free-associating intersection of art and literature—the picture book—that the curators of “Monsters and Miracles: A Journey Through Jewish Pictures Books” hope to pull viewers, young and old alike.

The exhibit is on view at The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts (413-658-1100;www.carlemuseum.org), from October 15 to January 23, 2011, with part of the show at the nearby National Yiddish Book Center (413-256-4900; www.yiddishbookcenter.org). The show debuted in April at Los Angeles’s Skirball Cultural Center.

The idea is to look at picture books as a window on Jewish life, and to look at Jewish life as an excuse to understand how the picture book has evolved,” said Ilan Stavans, Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. Stavans conceived “Monsters and Miracles” with independent researcher and author Neal Sokol. The two are guest curators of the exhibit.

Haggadah shel Pesah,’ Trebitsch,

Moravia/Courtesy of Klau Library,

Cincinnati, Hebrew Union College–

Jewish Institute of Religion

“Monsters and Miracles” brings together over 130 original works of art—all of them high caliber. The exhibit sets the stage with early illustrated books, from a reproduction of a 1,000-year-old alef-bet primer to a book of fables from 16th-century Venice and a few 18th-century illuminated Haggadot, including one that depicts the luxurious Seder of the family that likely commissioned it.

But those works are examples of illustrated books that were not meant for children. In fact, the idea of children’s picture books did not really arise until the 19th century, and did not become popular until the 20th, according to Nicholas Clark, chief curator at the Carle.

“Sociologically, there was a growing recognition that you can educate a child if you entertain them at the same time,” Clark said. “Using the picture as a point of departure can be a very potent bridge to literacy.”

Jewish picture books, like Jewish fiction, are products of the Haskala, the Jewish Enlightenment that started in the late 1700s, according to Stavans. Prior to that time, Jews eschewed fiction in the same way they avoided art as a potential transgression of the biblical injunction against graven images.

“And yet, today, we produce fiction and artwork, and we have been able to bring them together in such a successful and powerful way that it feels as if it has always been this way,” Stavans said.

Around the time of the russian revolution in 1917, artists began experimenting with illustrations. On display is the dust jacket of Der Nister’s A Mayses mit a Hon. Dos Tsigele (The Story of a Rooster. A Goat), published in Petrograd in 1917, which Marc Chagall illustrated in simple lines with his signature dream-like style. Chagall’s contemporary, El Lissitzky, produced an illustrated version of the Passover folktale Had Gadya in 1919 in Kiev, using Yiddish letters with an Art-Nouveau flair that complement the avante-garde drawing of a goat leaping into a Haggada.

But most of the works in “Monsters and Miracles” are from the last 50 years,when children’s literature has boomed worldwide and innovation and artistry have seeped into the exploration of Jewish identity.

& Giroux, LLC. The Collection of Eric and Barbara Carle. Courtesy

of The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art.

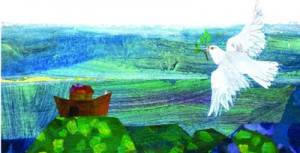

Rather than organize the exhibition chronologically, the curators pulled out themes—or chapters. One of the most fertile areas of children’s literature is Bible stories, the first chapter of the show. Illustrators, as much as authors, have the task of making scary and adult themes—sin, punishment, violence—accessible to children. Mordicai Gerstein renders a midrashic spinoff of the binding of Isaac in whimsical oil paintings with pencil for The White Ram: A Story of Abraham And Isaac (Holiday House). Eric Carle used his signature collage of delicate textures and combed colors for Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Why Noah Chose the Dove

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux).

Mark Podwal, who has works in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, went for a heavier blur in his gouache of the demon king Ashmedai in Elie Wiesel’s King Solomon and His Magic Ring (Greenwillow Books). Podwal depicts half the bearded and crowned bust of the demon in garish jewel tones and swirls of color as the fangs and scars begin to submerge beneath neutral flesh tones when Ashmedai transforms himself into a King Solomon look-alike. Demons are a favorite subject for Podwal, who figures prominently in the next section on golems, dybbuks and other mythical creatures.

(Greenwillow Books, 1999).

Courtesy of Dr. Rita Rothfleisch.

Reprinted with permission

Many illustrators employ spooky grays and foreboding browns, such as Trina Schart Hyman in her illustrations for Eric Kimmel’s Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins (Holiday House). David Wisniewski brings to life the red fury of the mob in Golem

(Clarion Books), using raised layers of intricate papercuts to create a fearsome relief.

“Jewish picture books have employed monsters to address an ever-expanding range of childhood emotions and experiences, often in unexpectedly sophisticated and humorous ways,” wrote Tal Gozani, associate curator at the Skirball, in an essay in the exhibit catalog.

The catalog, featuring essays and color reproductions as well as a Cricket Magazinecreated as a companion to the exhibit, offers a deeper look at some of the authors and illustrators. The Cricket issue, published with Sokol as guest editor in April 2010, contains commissioned works by Lisa Brown, Daniel Pinkwater and Stavans as well as an interview with Carle. One article provides the backstory to Maurice Sendak’s creatures in Where the Wild Things Are (HarperCollins). With names like Moishe, Tzippy, Aaron and Emil, they were based on Sendak’s East European relatives, who showed up at his childhood home loud and hungry, pinching his cheeks and promising to eat him up.

The Carle has two preliminary drawings from the Sendak classic, one of Max in a sturdy sailboat and the other of him leaving the land of the wild things as they beg him, “Oh, please don’t go—we’ll eat you up—we love you so.”

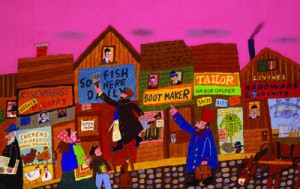

Caldecott Medal-winner Simms Taback uses telling details to populate his villages in the vivid multimedia collages for Joseph Had a Little Overcoat

Caldecott Medal-winner Simms Taback uses telling details to populate his villages in the vivid multimedia collages for Joseph Had a Little Overcoat and Kibitzers and Fools: Tales My Zayda Told Me

(both Viking). A look at his books reveals black-and-white ancestral photos and Yiddish folk sayings hanging in characters’ homes and streets drawn in pen, colored pencil, watercolor and gouache.

Vestiges of shtetl life continue in the exhibit’s chapter on transitions from the Old World to the New. Boris Kulikov’s caricature-like paintings for Linda Heller’s The Castle on Hester Street (Simon & Schuster) bring humor to the immigrant experience: In relating his coming-to-America story, Grandpa claims to have been greeted off the boat by President Theodore Roosevelt, but Grandma reminds him of the humiliating physical exam at the immigration center.

The transitions section deals with contemporary challenges. Richard Michelson’s Too Young for Yiddish (Charlesbridge), illustrated by Neil Waldman, looks at the thinning of Jewish identity over generations; his Across the Alley

(Putnam) explores a friendship between a black boy and a Jewish boy as a neighborhood changes, with illustrations by award-winning African-American illustrator E.B. Lewis.

Even the Holocaust is dealt with both explicitly and obliquely in children’s works. Playwright Tony Kushner and Sendak teamed up in 2003 to produce a version of Brundibar (Hyperion), the 1938 operetta performed at the Terezin concentration camp. “Monsters and Miracles” includes a preliminary drawing in which the book’s villain resembles Hitler. In the end, Sendak opted for what he called a “Napoleonic monstrosity.”

Michael Morpurgo’s The Mozart Question (Walker Books) is one of the more explicit treatments. Artist Michael Foreman captures the despair of members of a concentration camp orchestra as they play cellos and violins near the railroad tracks; the stony guards and terrified Jews are tinged with the same blue that shadows the snow around them.

Louise Borden’s The Journey That Saved Curious George: The True Wartime Escape of Margaret and H.A. Rey (Houghton Mifflin), with line and watercolor giclee prints by Allan Drummond, tells how the Reys fled Paris in 1940, carrying in their knapsack a manuscript about a mischievous monkey.

Unfortunately, the Reys’ inspiring tale, and other background stories, might easily be missed. The authors’ and illustrators’ personal histories are only offered in a limited way through informational panels.

The exhibit has the books from which the featured illustrations came, and it is worth the time to stop by the reading benches to take in some of the stories and the authors’ biographies, included in most of the books.

For example, Shulevitz, a Caldecott Medal winner, delves into his own life story in his two most recent works, How I Learned Geography and When I Wore My Sailor Suit

(both Farrar, Straus & Giroux). “Shulevitz manages to convey so much with such simplicity of language and artwork,” said Sokol. “When he turned to his own biographical material, his own escape from Poland, I found it to be one of the most remarkable pieces of testimony I had ever encountered in a piece of literature for children.”

Sokol did much of the detective work for the exhibition. He took a year to track down Shulevitz and almost as long to convince him to be part of “Monsters and Miracles.”

Stavans and Sokol included international artists such as French illustrator Serge Bloch, Great Britain’s Michael Rosen and Brazilian Lasar Segall, who was banned by the Nazis. Renowned in their own continents, these artists are not as popular in America. “Sometimes I felt like I was the mischievous kid holding the door open in the back of the theater asking all the artists to come in,” said Sokol.

Many of the authors he found were not, for the most part, producing explicitly Jewish works. Pinkwater, for example, just this year published his first book with overtly Jewish characters, and Daniel Handler only recently wrote a book about the Hanukka-Christmas dilemma.

Sokol also included artists who were not known primarily as children’s illustrators, such as David Polonsky, art director for the Academy Award-nominated animated film Waltz With Bashir and the illustrator of Ephraim Sidon’s The Bible in Rhymes: Genesis (in Hebrew; Am Oved), in which he used digital prints.

Sokol said he was inspired to think about children’s literature when his first child, a daughter, Mazal, was born in France in 2005. “The experience,” he noted, “had me questioning: What kind of environment can we create for her that will help her imagination thrive?”

He began sending books to Stavans. Sokol had written Ilan Stavans: Eight Conversations (University of Wisconsin Press), and Stavans had edited The Oxford Book of Jewish Stories

(Oxford University Press). The two thought about producing an anthology of Jewish children’s stories, which morphed into the exhibition. First the Carle and then the Skirball signed on to fund and produce the $500,000 endeavor.

The institutions brought divergent perspectives to the exhibit. The Skirball favors an interdisciplinary approach in telling the Jewish story and its intersection with American values. Carle, a prolific children’s author, founded his museum to display picture book art as art.

But the two converge at an important point: They both seek to introduce young people to the joys of art and culture, serving as bridge between children’s discovery museums and adult-oriented museums.

At the Skirball, viewers entered through a 12-foot-tall picture book. Doorways were made to look like book spines, with life-size pictures of figures from Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins and Gerstein’s rendition of Jonah and the whale. Kids were drawn to reading areas, stocked with books and headsets, which played recordings of books read by authors and celebrities—Ed Asner, Mayim Bialik and Henry Winkler. Children could sit at a play Seder, write stories and dress up monster mannequins.

The Carle has a simpler display, without play areas and large illustrations. But the books are available in the galleries, the audio at the National Yiddish Book Center, and children can create their own works at a studio outside the Carle gallery space.

Clark noted, “I think both museums will achieve the same effect in terms of people walking away having had their eyes opened to the richness and breadth of the material.”

The final section, on changing trends—including computer illustrations and the transition to digital media—is at the National Yiddish Book Center. The section has some payoff for kids: stills and resin figures used in the making of the feature films Shrek and Where the Wild Things Are

.

Pinkwater, an NPR commentator, contributed Beautiful Yetta: The Yiddish Chicken (Feiwel & Friends), illustrated in watercolor and marker by his wife, Jill Pinkwater. In it, a Yiddish-speaking chicken with blue eyes escapes from Mr. Flegleman’s farm truck and finds herself taken in by a flock of Spanish-speaking wild parrots.

Illustration © 2007 by Lisa Browne

Yetta, along with Laurel Snyder’s Baxter, the Pig Who Wanted to Be Kosher(Tricycle Press), are examples of books with a contemporary irreverent sincerity—a struggle to figure out what it means to be Jewish in the 21st century, when all traditional categories have been muddled.

That sort of modern conundrum, and the use of computer graphics, qualified The Latke Who Couldn’t Stop Screaming: A Christmas Story(McSweeney’s Books) for this section. Handler, known as Lemony Snicket, collaborated with his wife, illustrator Lisa Brown, to create a tale about a latke who asserts his identity above all the Christmas cheer. The latke is painted with sweat drops springing from its face, while Christmas is rendered in angular digital flatness.

While Art Spiegelman’s graphic-novel treatment of the Hasidic parable “Prince Rooster” (from his Little Lit: Folklore & Fairy Tale Funnies; RAW Junior) is in the shtetl life section, the graphic novel genre is represented in the final section with pages from The Adventures of Rabbi Harvey: A Graphic Novel of Jewish Wisdom And Wit in the Wild West

(Jewish Lights) by Steve Sheinkin and Houdini: The Handcuff King

(Hyperion), by Jason Lutes with illustrations by Nick Bertozzi.

What you do not have in the section is an iPad or Kindle. But the curators are aware of the digital upheaval in publishing. Stavans said he is not worried. Jews have adapted their storytelling, he said, and they will continue to do so as technology advances.

“The Jewish picture book is alive and well and kicking and doing all sorts of pirouettes in extraordinary fashion,” he notes. “This exhibit catches it at a prime moment, and I don’t foresee any decline, because there is more need for it than ever. We are hungry to find out who we are, and the picture book is one way to explore our own identity.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply