Family

Feature

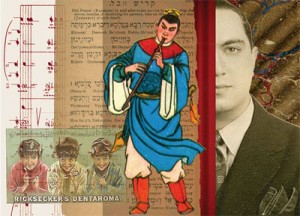

Family Matters: Mourning Offstage

“The Jewish religion provides an exquisitely structured approach to mourning.”—Rabbi Maurice Lamm, The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning (Jonathan David Publishers).

Everyone observing aveilut, the traditional yearlong mourning for a parent, finds a different aspect of the restrictions most challenging. For me, it was not going to the theater.

As both public event and organized entertainment, theater is discouraged during aveilut, as are operas, concerts and movies. Though the basis of aveilut is the avoidance of music and, some would say, of sacred celebrations, “committed Jews,” writes Lamm, “avoid both religious and social festivities.”

Aveilut for a parent incorporates not only the weeklong shiva and the 30 days of sheloshim, but lasts a full 12 months because it includes the mitzva of honoring one’s father and mother. When questioning what is permitted during aveilut, I had to consider what actions and activities my father would consider to honor or dishonor him. In the case of my father and theater, it might have been difficult for him to answer.

My father, Rabbi Isaac N. Trainin, was a Jewish communal servant his entire life. He spent 55 years at the Jewish Federation of New York—later UJA-Federation—as director of religious affairs and founding director of the Commission on Synagogue Relations. He carved out a gadfly niche to fulfill unmet needs. He bridged the gap between the religious world and the secular philanthropic world. He established or inspired programs and agencies for Jewish alcoholics, premarital counseling, the unrecognized Jewish poor, disenfranchised women and myriad others.

But my father was also a culture vulture. My passion for theater came to a large extent from him. I didn’t see my father much during the week—he was often at meetings late into the night. This made Shabbat even more special, as we filled the day with such things as singing zemirot, studying the parasha, taking walks and napping. But then, on cold, rainy days or long, hot summer ones, we would put on musicals and plays.

My father, brother and I would divvy up the parts—be they in Lerner and Loewe or Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals or in scripts by Ibsen, Shaw and Miller—and recite them out loud in a kind of staged reading. My father served as both “script-selecting committee,” at least until my brother and I developed preferences of our own, and as director-actor. With my mother often napping, the three of us had to balance multiple parts. When my brother entered high school and participated less, my father and I had an even bigger juggling act. It was amazing how many scripts and scores my father owned—part of an ever-growing library of secular and Judaic works that seemed to devour the apartment.

By the time I was 12, my parents had taken me not only to Broadway and Off Broadway shows but to ballet, classical concerts and operas. I loved every minute of those experiences.

With this background, it was a great thrill to be asked later in my life—no longer in New York and married—to be a second-string theater reviewer for the local newspaper in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. That lasted an idyllic nine years, during which I was treated to dozens of plays free of charge.

So it was with some trepidation and a great measure of sadness that I faced a year without theater after my father’s death. I sat down with Chaim Schertz, our now-retired rabbi, and the first halakhic question I posed concerned theater. Emphasizing that parnasa (making a livelihood) meant a musician could play at a concert and I could attend theater as a critic, he suggested avoiding comedies and musicals, at least.

Then, Rabbi Schertz urged me to take into account what my father would consider respectful—and, again, I was left with that unanswered question.

But since aveilut is a public as well as a private observance, and since I wanted my own children to learn about honoring one’s parents, I decided to avoid anything but serious drama. Even so, I was uncomfortable. Would people who knew I was in aveilut understand the distinction?

At first I just squirmed when theater friends asked me if I would be attending this play or that. Finally, I started telling them the reason I could not. They had already gotten used to my being unable to come on Friday nights, some Saturday nights in the summer, all major Jewish holidays, etc. And that wasn’t easy in a part of the country with a small Jewish community. But many of them were sympathetic—they told me they respected my devotion to my religion. Ironically, theater became a symbol of my Jewishness.

It also became a symbol of my connection to my father. When friends express surprise that I have read or seen so many plays, I tell them honestly it was due to him. There are so many legacies my father left in which to find joy and comfort: his love of Jewish learning and devotion to the community as well the courage to fight for what he believed in—and a sense that he had really changed the world. The bridge legacy, perhaps, was the drama my father found in the stories in the Tanakh and the Talmud—their human conflicts. What is drama if not conflict? His interpretations of the stories of the patriarchs and matriarchs in the Book of Genesis were a bit unorthodox—my father, for example, found Esau a more redeemable character than the rabbis did—but it was clear he loved to teach, surprise, tell jokes and dramatize.

Secular theater remains a part of that legacy, although my father would always point out with pride how much American theater (and classic movies) owed to Jewish playwrights, composers, lyricists and actors.

Still, aveilut, while burdensome, is also a relief and a vehicle for healing. While I was doing research for a preview of the play Rabbit Hole, about a couple who loses a young child, a chaplain-bereavement counselor noted the difference between grief—an automatic response to loss—and mourning, a private and public acknowledgment of the loss. People who grieve without mourning, he said, have a harder time finding relief and reaching out to others.

Just as we reach for that first bagel after Pesah, or the first morsel of anything after the fast of Yom Kippur, so going to the theater again after aveilut was both extra sweet—and bittersweet. Would I remember my father in my life as actively without the reminders of deprivation? Yes, I did. I could “hear” his voice arguing with me about this performance or that play. Whether a certain composer was really Jewish or what an actor’s original name was. My father was a font of theatrical information, insight and inspiration. Yes, he would remind me, the stories in Bereshit made for great drama. And, yes, Esau wasn’t so bad because he did, at least, respect his father.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply