Arts

Music

Personality

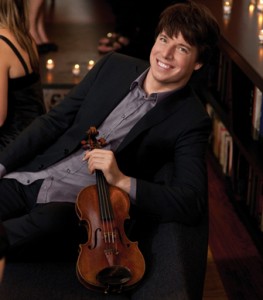

Profile: Joshua Bell

For a few minutes at least, violin virtuoso Joshua Bell relaxes in his New York apartment. Zealously promoting his new CD, Joshua Bell at Home With Friends, he has been up since 5 A.M. for a taping of the Today show and by nightfall will be in Los Angeles for the Tonight Show. His constant companion, the “Gibson Ex-Huberman” 1713 Stradivarius violin—valued at $4 million—is packed away, but he will soon take it on the road for concerts in Chicago, Stockholm, Moscow, Berlin and Vienna. This schedule, Bell pronounces, is part of “a typical month.”

Critics have characterized the 42-year-old’s playing by superlatives like luxuriant, sumptuous, ardent, and heart-melting. When he plays, he moves his upper body with the sensuous grace of a dancer, sometimes looking intently at the violin, sometimes closing his eyes, focused on telling a story, sweet or sorrowful. Closer to the human voice than any other instrument, the sound of the violin “goes right to the soul,” notes Bell.

It is hard not to be dazzled by Bell’s talent; his good looks don’t hurt, either. In a gray sweater, black pants and black boots, he is a boyish cross between Paul McCartney and David Cassidy. Teenagers wait for him backstage after concerts, hoping for photos and autographs, and more mature musicians swoon over his masterful song interpretations. Over the past two decades, he has amassed awards too numerous to detail, including a Grammy for his recording of Nicolas Maw’s “Violin Concerto,” which the composer wrote especially for him, and an Avery Fisher Prize in 2007 for outstanding achievement. He performed on the soundtrack of the Oscar-winning film The Red Violin and the Holocaust-related Defiance. He has also appeared on Sesame Street and was even the subject of a question on the television game show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

Bell’s love of violin began when his parents bought him a junior instrument at the age of 4, after they noticed him replicating classical tunes with rubber bands he had stretched around the handles of his dresser drawers—one of his earliest memories. Though he hates the word “crossover,” his willingness to experiment with different styles has spread his fame beyond the classical music world. His newest CD, which reached the top of Billboard‘s classical charts within days of its fall release, is the latest of his more than 35 recordings. On it, Bell performs duets with musicians from diverse genres: a stirring rendition of George Gershwin’s “I Loves You Porgy” with trumpeter and former Indiana University classmate Chris Botti; a tender 16th-century love song with Sting; a lyrical “Cinema Paradiso” with Josh Groban; and “My Funny Valentine” with Broadway and television star Kristen Chenoweth. Bell’s range shines in unexpected partnerships, matching the Latin beat of Tiempo Libre; the bluegrass rhythms strummed by double bassist Edgar Meyer (another former classmate) and the entrancing ragas of Anoushka Shankar’s sitar. A televised concert, airing January 21 on PBS, will feature Bell performing at Lincoln Center with Chenoweth, baritone Nathan Gunn, pianist and composer Marvin Hamlisch, musician Frankie Moreno and Tiempo Libre.

“Joshua has helped promulgate the cause of great music,” says Steve Epstein, who produced the new CD as well as other Bell albums. “He’s forthcoming and disarming and has done a lot to attract those who may think of classical music as elitist and not immediately accessible.” During his work on this album, Epstein says he was amazed by Bell’s versatility and ability to adapt to so many styles. He adds that Bell is “very modest for someone of his talent and ability. He’s very secure in what he does.”

The CD was inspired by the informal “musicales” that Bell holds frequently at home, modeled after family soirees during his childhood in Bloomington, Indiana: His two sisters, parents and cousins all played together during holidays, a combination of cello, violin, flute, piano and clarinet. He spent three years renovating and designing a living space that can easily morph into a performance area for the intimate, freewheeling salons. The warm wood floors call to mind the maple and ebony of the Stradivarius, balanced by contemporary charcoal-gray sofas. Friends and guests sit on chairs, on pillows on the floor, or line the staircase up to a glass-enclosed balcony overlooking the living room and a roof garden.

Though he is hardly a folksy Chagallian fiddler, Bell does continue the tradition of Jewish violinists—Yehudi Menuhin, Jascha Heifetz, Isaac Stern, Itzhak Perlman and Pinchas Zukerman. “At one time, almost all the great violinists were Jewish, so it was something Jewish kids could aspire to and emulate,” says Bell, who considers himself secular, with a cultural attachment to Judaism.

Its eclectic range aside, does the violin have a “Jewish” sound? “Yeah,” Bell answers unhesitatingly, “it does. There’s something about the violin that’s such a part of Jewish culture. There’s an old saying in Israel: If you see someone walking down the street and they don’t have a violin case, it’s because they play the piano.”

Even Bell’s chosen instrument continues the Jewish chain. Once owned by 19th-century violinist Alfred Gibson, the violin became the prized possession of Polish-born Bronislaw Huberman, the Israel Philharmonic founder who performed Brahms’Violin Concerto on it at age 14 for Brahms himself. In 1936, the violin was stolen from Huberman’s dressing room at Carnegie Hall by a minor New York violinist. It was recovered after a deathbed confession in 1985, and in 2001, Bell discovered it was about to be sold to a German industrialist. “I was practically in tears,” recalls Bell on his Web site (www.joshuabell.com). He sold his own Tom Taylor Stradivarius for a little more than $2 million and borrowed the rest. Bell couldn’t stand to see the instrument go to an investor, whose interest would be in profit, rather than having it be in the hands of a musician who could let it continue to be played as it was meant to.

“I’m proud to have the violin Huberman owned,” Bell says. “It’s the most amazing-sounding violin I have ever heard. I mostly have a love relationship with it—sometimes love-hate when it’s not cooperating.”

Bell’s Poland performance in October took place in Huberman’s birthplace of Czestochowa; the city’s Philharmonic Hall is the former site of the New Synagogue. His Warsaw concert raised funds for the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, to be built on the site of the former Jewish ghetto. “My grandmother was from Belarus,” says Bell; his maternal grandfather was a sabra. “Being in that area, there’s something that feels like home to me.” Bell also performed at the White House last November, and he is looking forward to a series of six concerts in Jerusalem in May, when he plans to visit his Israeli cousins.

Charlie Hamlen, Bell’s first manager and founder of IMG Artists, says Bell “connects to what the composer wants—and makes it happen. That complete connection is rare. His music-making has real character. You feel as though you are hearing the music for the first time, and if [it’s] not the first time, it stirs you in a different way.”

Amidst a collection of autographed photographs of maestros that hang on the wall of his library, Bell points out his teacher, Josef Gingold, who was also Jewish. Many of the photos originally resided in Gingold’s studio. Bell studied with Gingold for nine years, from the age of 12. In an April 2004 Readers Digest article, Bell wrote touchingly of the musician: “I had never met anyone who found music so fun. He would play two parts of a string quartet at once. He laughed and laughed, and I left those lessons buzzing…. My teacher taught me that music could be more than a hobby. It could be a life…. He helped me create a very personal relationship with music but he did not teach me to play every note…. He became the grandfather I didn’t have.”

The Bell family moved from New York to a 20-acre former farm with a 1830s log house in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1967. Bell’s father, psychoanalyst Alan Bell, took a job as research psychologist in the area of human sexuality at the Kinsey Institute, on the campus of Indiana University; his mother, Shirley, has degrees in counseling. Though the Bells were both musical, they had no idea that Indiana had a renowned music school with faculty members like Gingold. But Bell’s relationship with Gingold almost didn’t happen. The day before his first major solo recital at the university at age 12, Bell sliced his chin open while tossing a boomerang. “The ER doctor stitched me up,” recalls Bell. Two inches to the left and I couldn’t have held my violin. But I played, wounded. Someone convinced Gingold to come to the recital. He liked what he heard.”

Despite his prodigious talent, Bell’s parents encouraged a normal childhood. Gifted in many areas, he played sports, computer and video games. Because he learned quickly and easily, he didn’t spend too much time practicing violin. Gingold’s philosophy was equally relaxed: When Bell’s mother told him her son had spent all day playing video games instead of practicing, he was “secretly pleased,” according to Bell.

Nonetheless, Bell won a national talent competition that earned him a solo debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra when he was 14 and catapulted him to fame. He made his Carnegie Hall debut in 1985, his first classical recording at 18. After Bell moved to New York at the age of 21, he didn’t see Gingold as much as he would have liked. He visited him on New Years Day 1995, bringing a photograph to autograph. “In his hand he had one last gift for me—a rare picture of Niccolo Paganini, the crown jewel of his studio collection,” writes Bell. “The next day he had a stroke. He died two weeks later.”

Bell’s 2-year-old son, Josef, with former girlfriend Lisa Matricardi, is named after Gingold. He and Matricardi are still close friends and the two are expecting twins in March. Marriage would be a challenge, Bell says candidly, noting that he is on the road 250 days a year. “It’s not easy to have a Leave It to Beaver family.” He recently brought Josef to a dress rehearsal with the New York Philharmonic. “In the middle of the rehearsal, I heard, ‘Dada!'” Bell says and laughs. “I won’t push him into the music world—well, maybe I will push him a little. I want him to have music in his life whether or not he becomes a musician. He will no doubt experience how much joy I get out of music.”

“Josh loves to master his environment,” says his mother, Shirley Bell. “Everything becomes a challenge: That’s what he looks for in life.” A natural athlete with “consistency, focus and determination,” in his mother’s words, he placed fourth in a national tennis championship at age 10—without a lesson—among other accomplishments.

While already a soloist and performer with the local symphony as a child, he declared in a radio interview that he wanted to be either a scientist or detective. He took great interest in physics and technology, surprising his parents when he settled on music. His résumé highlights his world championship title for the computer pinball game, Crystal Caliburn, in which the Knights of the Round Table pursue the Holy Grail, and his work on a Massachusetts Institute of Technology project to develop a computer-enhanced “hyperviolin,” a high-tech electronic instrument played with an electronic bow.

“I want to do everything,” says Bell. “I want to try everything. Travel everywhere I can. You only get one shot at life so you should live every day like it may be your last. It’s clichéd but not everyone lives by that.” He is self-admittedly passionate—”obsessive by nature”—these days about food. He has been an avid golfer and now “lives for” Sunday football. His fun-loving nature is evident when he drives his deep purple Porsche. From his father, he absorbed an intense work ethic; from his mother, an attraction to risk and, he says, a “slight gambling addiction.” To be a musician, he notes, “you have to think like a youthful person and not lose your sense of curiosity and exploration.”

Probably his most well-known adventure was the social experiment he participated in at the request of Washington Postcolumnist Gene Weingarten on January 12, 2007. For 43 minutes, in the middle of the morning rush hour, Bell played six classical pieces at the D.C. Metro L’Enfant Plaza station. Of the 1,097 people who passed by, only 7 stopped to listen and 27 donated money, earning Bell a grand total of $32.17. Weingarten’s subsequent story, “Pearls Before Breakfast,” garnered a Pulitzer Prize. Bell says he learned that when he plays for ticket-holders, he is already validated; in the subway he was without a frame: “Performances need to be in a specific context to be fully appreciated,” he notes.

Bell’s musical risk-taking doesn’t exactly make him Evel Knievel, he says self-deprecatingly. He is skilled at improvising cadenzas, embellishing and adding ornaments to freshen and enliven the familiar. His collaborations are adventures of a sort, too, he says: “There’s a misconception about other kinds of music. I thought I had good rhythm until I played with Edgar Meyer. His precision made me sharpen my whole sense of time. I can bring that back to classical music.” It’s good to remember, he says, “that the essence of music is not necessarily the dotted i’s and crossed t’s.” He stops, “I don’t want to reinforce the stereotype of classical music as rigid and stuffy. We get bogged down in details and playing with other musicians is freeing.”

His latest adventure, besides parenting, is teaching, as a faculty member at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music. Starting with small doses, he foresees playing a new role in the future: that of mentor. “It’s like having good parents and wanting to be a parent yourself,” he says. “I want to pass on the musical values I’ve inherited.” H

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply