Israeli Scene

Feature

Letter from Tel Aviv: Sacred Night in a Secular Place

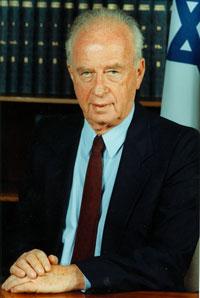

One day every year, Israelis—mostly secular—take time to mourn, celebrate and remember fallen Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and the era of hope that he symbolized.

One day every year, Israelis—mostly secular—take time to mourn, celebrate and remember fallen Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and the era of hope that he symbolized.

On November 4th, as darkness falls, people begin to arrive by the thousands at Rabin Square in Tel Aviv. Some come on foot, walking in loose columns through the city’s streets and boulevards, the long nighttime shadows of jacaranda and ficus trees falling alongside their own; others travel by car or buses from outside the city.

They converge, as they have every year since a Jewish extremist shot Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on that November day here, in the city’s largest square. They have come to mourn their fallen leader and the hopes for peace and a different Middle East that he symbolized.

It has been 14 years since Yigal Amir, then a 25-year-old religious, right-wing law student, fired three bullets into Rabin’s back at the end of a mass peace rally. Amir said he acted to stop the peace process with the Palestinians. In bitter tones, some Israelis agree: He has succeeded.

The week after the assassination, a record 250,000 to 300,000 people gathered in the square, about five percent of the entire population of Israel. Today, the event can draw as many as 100,000.

The streets surrounding the square are blocked to all traffic and, at moments, there is a festive air amid the more sober reflections. Israeli flags ring the square, and the fall breeze stirs up the helium-filled balloons, many marked with the logo of Peace Now. Using cellular phones, friends and relatives locate each other and greet with long embraces. Shoulder to shoulder, men, women and children sing songs and listen to speeches. Young couples push infants in strollers; white-bearded grandfathers hoist grandchildren on their shoulders and teenage members of left-leaning youth movements hold up handwritten signs in magic marker calling for peace.

“I go because I feel it’s important to stand and be counted,” said Michal Levy, 28, “but also because I want to feel I am part of something larger on that day, like part of a group that [feels] the same things.” Levy was 14 the year of the assassination. She was among the teenagers who gathered in the square in the weeks that followed, covering it with yortzeit candles and singing peace songs; her generation, which came of age in the shadow of Rabin’s murder, became known as the “Children of the Candles.” The residue of dark wax stains is still visible on the paving stones in the northern tip of the square where many youth sat and grieved.

“We go to remember something that opened up a great chasm in Israeli society,” said Dahlia Scheindlin, 37, a political pollster. “We go…to remind each other we should never again turn on one another.” Scheindlin made aliya shortly before the second anniversary of the assassination and has been to many of the memorial gatherings. She recalled the shock and grief that hung over the crowd in the early years and has watched as the event has formalized and the feelings of raw emotions evolved.

According to Vered Vinitzky-Seroussi, a sociologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the gathering has become “a new annual social ritual: a memorial demonstration.”

Most participants are members of the country’s peace camp, and many of them still blame the country’s religious right wing for the atmosphere of incitement against Rabin. Beyond the political aspect, she writes in her forthcoming book, Yitzhak Rabin’s Assassination and the Dilemmas of Commemoration (SUNY Press), the ceremony has become a central event “for a secular group with no synagogue that needs a place to mourn.”

“The November memorial has become like a tribal gathering around the fire,” said Eitan Haber, Rabin’s chief of staff and for years his closest confidante.

It was the grief-dazed Haber who stood outside the entrance of Tel Aviv’s Ichilov Hospital, where Rabin was taken, and spoke words that Israel is still trying to absorb: “The government of Israel announces, with astonishment, that Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin has been shot, killed by a Jewish assassin.” A video clip of that searing announcement is broadcast across the square on giant screens at each gathering.

Excerpts from Rabin’s final speech are also replayed. His low, gravely voice booms through the square with the haunting lines: “Violence is gnawing away at Israel’s democratic foundation. It must be condemned, denounced and isolated. This is not the way of the State of Israel.”

Haber is among the small circle of organizers headed by Dalia Rabin-Pelosoff, the prime minister’s daughter, who plan the memorial under the unofficial auspices of the Rabin Center, the institute founded in his memory. They select speakers—authors, politicians and civic leaders—as well as popular singers.

“Every year we think that not many people will still come,” Haber said, “and every year, with no explanation, people come with their kids and grandchildren, including those who were not even alive when Rabin was murdered.”

“[Preparing the program line-up] is always a very complicated process because we do not want to be too political,” noted Rabin-Pelosoff. “On the other hand, the assassination was a political assassination.”

In addition to the video, every rally includes a number of core components: Classic Israeli songs, from Rabin’s favorite, “The Song of Comradeship” (dating to his days in the elite prestate Palmah, it recounts the glory of fallen soldiers) to “It Will Be Good,” with its perfunctory line about withdrawing from the Palestinian territories; a moment of silence at the exact time of the assassination (9:40 P.M.); and a film clip of Rabin’s life including his famous handshake with Jordan’s King Hussein and shots from his funeral with the tune of “Shalom, Friend” playing in the background. There is always a speech by a member of Rabin’s family against a large red, black and white backdrop with Rabin’s photo next to the number of the anniversary year and a rupture line running across the width of the entire poster.

“The Song of Peace,” the peace camp’s unofficial anthem, is sung by folksinger Miri Aloni, who performed at that fateful rally 14 years ago, and brings the ceremony to a close. And, like at any Israeli ceremony, the grace note is “Hatikva,” the national anthem.

There is a feeling that the past is not only being reenacted, but almost preserved.

Despite its organizers’ protests that it is not a political event, those from the Israeli right wing and the National Religious camp tend to stay away, a reflection of ongoing schisms.

Compounding the divisions, there are even different days to memorialize Rabin: November 4th, the anniversary of his death according to the Gregorian calender; and the 12th of the Hebrew month of Heshvan, this year October 30, officially mandated as national Rabin Memorial Day. It is when schools hold memorial assemblies, the Knesset has a special session and a ceremony takes place at the state military cemetery on Mount Herzl.

“I think the memory of Rabin needs to be preserved for the entire nation without relation to which political or religious camp a person might come from,” Haber said. “The man himself is no longer with us and his vision for peace is for us to follow through on.”

But Rabin’s vision for peace is still a matter of intense dispute, and politicians and activists on the left claim the Israeli right never underwent a heshbon ha-nefesh, spiritual accounting, for their role in the volatile atmosphere in the weeks before of the assassination.

Every year, the Rabin Center sends out educational materials to schools and Army bases with suggestions for memorial ceremonies based on themes such as leadership, civil society and democracy. However, many of the packages sent to state religious schools are returned, unopened.

Although schools must observe the anniversary of Rabin’s death, said Vinitzky-Seroussi, state religious schools in the ideological West Bank settlements usually do not. Some feel that observing Rabin Memorial Day implies agreement with his politics.

“I think the day needs to be marked, so we put his photo at the entrance to the school along with a timeline of his life,” said Hagit Selah, principal of a state religious elementary school in the West Bank settlement of Ofra. However, she added, she does not run a school-wide ceremony, something she used to do when she worked at a Jerusalem school. “Here there is so much division of opinion on the subject, so instead we hold discussions in the classroom [which include] lessons on Rabin and tolerance. I think one has to emphasize to the children that this was a terrible thing, a Jew killing a Jew over a difference of opinion.”

Yossi Sarid, former head of the left-wing Meretz Party, who authored the Knesset bill creating Rabin Memorial Day, now regrets the legislation: “Something like this needs to speak to the heart of the public and not come out sounding like a decree. It’s not worth having a memorial day if there are segments of society that do not voluntarily observe it or do so only out of politeness.”

Zevulen Orlev, a veteran politician and member of the Ha-bayit Ha-yehudi (Jewish Home) Party, attends all official state ceremonies marking Rabin Memorial Day, but he has never gone to the gathering at Rabin Square.

“We in the Zionist religious camp are full partners in the national mourning,” he said. “For a citizen to take the law into his own hands and assassinate a prime minister is something we condemn in all possible ways. But unfortunately the day is being used by political players to try to advance their own agendas, and I think that’s a great mistake…. It diminishes the overall sense of national mourning.”

Indeed, over the years the gathering has reflected current political reality—and people’s grievances with it. Israeli author David Grossman, for example, chose the 2006 gathering as his first public address following the death of his son in the Second Lebanon War the previous summer.

“The annual memorial ceremony for Yitzhak Rabin is the moment when we pause for a while to remember Rabin the man, the leader,” said Grossman to the crowd. “And we also take a look at ourselves, at Israeli society, its leadership, the national mood, the state of the peace process, at ourselves as individuals in the face of national events.”

Daniel Robinson, 45, a travel writer and a regular memorial-goer, has an apartment that overlooks Rabin Square. He was among the crowd at the 1995 peace rally. “I think people go to the memorial gatherings feeling it’s a duty to go, both for Rabin and for their children,” he said. “It’s a way of having a sense that Rabin’s dream of peace is still possible.”

On a corner of Rabin Square near city hall, a modest memorial sculpture stands at the exact spot where Rabin was killed: Every year, in the days leading up to November 4th, it is piled high with wreaths of flowers tied with black sashes. Yortzeit candles are lit around its edges. The memorial itself is fashioned from large square blocks of rough-hewn basalt stone that emerge from the ground to symbolize the “earthquake” of this killing.

In the days following Rabin’s assassination, the outer walls of city hall near that spot were covered in a graffiti montage of public grief. People scribbled notes along with slogans such as “The World Shall Never Forget” and the ubiquitous “Shalom, Friend.” The graffiti was eventually covered up, but a large photographic reproduction of one of the walls as it was is on display nearby. It is dominated by large, blue Hebrew letters that form the word “Seliha,” forgiveness—or, perhaps, forgive us. H

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply