Arts

Personality

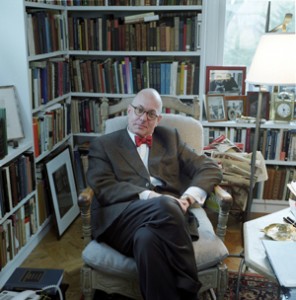

Profile: Leon Botstein

This college president and orchestra conductor has made waves both for his promotion of controversial educational experiences and for his resurrection through repertoire of ‘unfairly forgotten’ classical musicians.

In the president’s house at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, an idealized marble bust of Beethoven is festooned with hats. Both the bust and the headgear belong to Leon Botstein, who has headed the college since 1975 and wears several hats himself.

In addition to his academic career, which began at age 23 when he was chosen president of the now-defunct Franconia College (the youngest college president ever), Botstein is music director and principal conductor of both the American and Jerusalem Symphony Orchestras—he travels about 10 times a year to Israel—and a guest conductor with many others. He is also a historian, author, critic and leading advocate of progressive education.

Botstein (pronounced bot-stine) often performs works by composers most audiences have never heard of. It is precisely these composers who, unlike Beethoven, have been “unfairly forgotten” that Botstein is on a crusade to redeem. He berates the choice of repeatedly selected repertoires in concert performances as “ridiculous conservatism” and a “falsification of history, as if most rooms in a museum were closed,” or as if a reader’s only option were War and Peace. His thematic, unconventional and critically acclaimed programming places musical works in the historic, political and cultural contexts that nourished them.

“Growing up, I never identified with Clark Gable or Mozart,” explains Botstein. “The journey to oblivion is not always justified. It’s not that Puccini and Beethoven were not great composers, but they were not the only ones. I champion the underdog.” In March 2008, for instance, he presented the first American performance of German Jewish composer Ferdinand Hiller’s powerful 1840 oratorio, The Destruction of Jerusalem. “The piece holds its own with the oratorios of [Felix] Mendelssohn,” wrote music critic Anthony Tommasini in The New York Times.

At Bard’s SummerScape music festival, a peek of Botstein’s bald head and his crisp, forceful gestures rise from the orchestra pit as he conducts a rehearsal of Karol Szymanowski’s 1931 operatic dance, Harnasie. Considered the father of modern Polish classical music, Szymanowski was a friend and contemporary of Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev. Botstein’s conducting is not showy or balletic, and after Act I he reviews the trouble spots with the orchestra. The winds begin, joined by strings, then percussion. “Do not be lazy, come in together,” he admonishes. “There’s always some lone sheep wandering from its pasture.”

Composer and pianist Richard Wilson has known Botstein for almost 50 years, and the two have collaborated on many projects. “He’s full of so many ideas,” says Wilson, “that in phone conversations my hand gets numb from holding the receiver.” Once, says Wilson, Botstein described his work as “planting a flower in the desert.” To overcome the odds of short rehearsal times, one-shot performances and unfamiliar scores presented in a highly competitive New York concert environment (such as Lincoln Center and Symphony Space) “requires idealism, optimism, risk-taking and an elaborate support system,” Wilson adds.

In the educational field, Botstein is a risk-taker who expresses strong views, espouses cutting-edge solutions and doesn’t mind controversy. “People are afraid of being punished for taking positions, so they gravitate to the bland center,” he says. “The truth is not always in the middle. In a position of leadership, you’re obligated to take a stand on important issues.”

In his book Jefferson’s Children: Education and the Promise of American Culture(Doubleday), Botstein explores his pioneering educational ideas, arguing that high school should end after grade 10 in favor of early college admission. “School is only a platform for life,” says Botstein, who himself graduated at 16 from the High School of Music and Art in New York. Curiosity is a “lifelong obligation,” but American schools can often “beat [it] out of you” through poor teaching, especially in the maths and sciences.

In 2001, Bard and the New York City Board of Education created the Bard High School Early College, an alternative to a traditional high school that allows students to earn two-year college associate degrees; a second branch opened in Queens last fall. Bard also owns Bard College of Simons Rock: The Early College in Great Barrington, Massachusetts; though they function separately, the close relationship enables Bard to develop a strong curriculum for younger students. Colleges and universities “can’t pull the blinds down on the crumbling infrastructure of American education,” says Botstein. “They have…to work toward improving it.”

In collaboration with institutions abroad, Bard introduces liberal educational values to countries in transition in Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, South Africa and Central Asia. Its latest and most comprehensive partnership is with the Palestinian Al-Quds University in Jerusalem, focusing on three joint efforts: a four-year liberal arts honors college; a master’s of arts in teaching; and an experimental high school, scheduled to open in fall 2010. Initial financing is being donated by the George Soros Foundation.

The partnership has generated some controversy in the American Jewish community, but, says Botstein, it was brokered by Israeli academic colleagues and has not provoked conflict in Israel: “Nothing could be better for democracy, economic progress and peace in the Middle East than a good educational infrastructure…. If we are concerned about Palestinian attitudes towards Israel and towards Jews, there is no better antidote than serious education based on critical dialogue.” Botstein points out that Hadassah’s founder, Henrietta Szold, favored a binational state, and that Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, also has a partnership with Al-Quds, though it is far less elaborate than Bard’s.

Bard has long emphasized small classes, interdisciplinary studies and the arts—once considered experimental concepts. Botstein has helped shape it into a central body surrounded by satellites specializing in writing and thinking; environmental policy; economics; curatorial studies; globalization and international affairs; and teacher training. He has raised funds tirelessly, doubled the undergraduate student population to 1,600, established a graduate school that now has 800 students, attracted notable faculty such as artist Roy Lichtenstein and writer Cynthia Ozick and burnished its reputation as “a place to think,” not just to take pre-professional courses. Bard’s “most remarkable arena” for learning, says Botstein, is its Prison Initiative, which allows inmates at four New York State prisons to earn associate and bachelor’s degrees.

“When Leon began, it was not clear Bard would survive; it is now widely recognized as a great college and cultural institution,” says Anthony Marx, president of Amherst College in Massachusetts. “The kind of leadership and innovation that can make such a difference to an institution is rare.”

Botstein received his bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Chicago and his master’s and Ph.D. in European history from Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He began playing violin when he was 11—“already too late to compete successfully at the highest level,” he says—studied conducting in college, graduate school and privately. He is coeditor of Vienna: Jews and the City of Music, 1870-1938 (Princeton University Press); editor of The Compleat Brahms: A Guide to the Musical Works of Johannes (W.W. Norton); and author of two forthcoming books—The History of Listening: How Music Creates Meaning (Basic Books), an historical inquiry into the function of music, and Music and Modernism(Yale University Press), a collection of his essays on the history of music.

In an appearance on The Colbert Report in 2007, Botstein showed his capacity for humor, poking fun at himself as a “caricature of a pointy-headed intellectual,” with his shaved head, thick round glasses and signature bowties. “You are not an evil mastermind, are you?” Colbert asked. “You look like you might be the evil intellectual character from some comic book where guys with giant brains are taking over the world.” Colbert continued: “What’s so great about intellectuals? They just think all the time.”

“Intellectuals actually ask questions,” Botstein answered. “They’re not satisfied with what they think everybody knows.”

A true scholar, Botstein’s answers frequently run to essay length. His study and living area at Bard teem with books on history, literature, philosophy and music (he has a separate score library in the basement); lithographs and photographs of composers from Verdi to Copeland; and other items such as Johann Strauss’s personal invitation to Brahms’s funeral, views of Jerusalem and a silver hanukkiyaalso decorate the space. His favorite composer, he says, is the one whose music he is currently working on. “You have to be loyal to the piece you are on brink of performing,” he explains. “It would be unfair being with one partner and thinking of another.”

Yet it was not until tragedy struck—literally—that he focused his career on music. On October 6, 1981, his two children, Sarah and Abby, left their mother’s house to catch a school bus. (Botstein’s marriage to his first wife, Jill Lundquist, had broken up.) Abby forgot something and as she crossed a busy street to return home, she was hit by a car and killed—on the eve of her 8th birthday. “The suddenness and unimaginable shock and loss is without question the most important event of my life,” says Botstein. “Nothing remotely compares. My life was shattered.”

Six weeks after the funeral, friends put together a memorial concert for Abby, who had been a gifted violinist, and suggested Botstein conduct. “I still think of her when I conduct because I owe her,” says Botstein. “It was a wake-up call to what was really important.”

His parents, Anne and Charles, no strangers to loss, helped him move forward. As medical students in Switzerland, they were spared the brutality of the Holocaust themselves, but almost their entire families perished. Coincidentally, both his parents were born in Russia and grew up in Lodz, Poland. Botstein’s maternal grandparents immigrated to Mexico in 1946 and his mother’s younger brother, Samuel, married the righteous gentile who hid and saved him.

Perhaps it is his sensitivity to great loss that spurs Botstein to reclaim the legacies of others on the verge of disappearance. Born in Zurich at the end of 1946, the youngest of three, he is named for a maternal uncle who died in the Warsaw Ghetto. The family immigrated to the United States and settled in the Bronx when Botstein was 2. The Holocaust was always a major subject of his childhood, he recalls, and his parents’ home was “rescue central” for emigrés in need. His parents had tried earlier to save their own families by sending 21 Swiss watches for barter and bribery—all of which arrived and were traded for food and favors. His Uncle Samuel used the last watch to bribe a Russian soldier in 1945.

In commemoration, Botstein collects grandfather clocks, timepieces and pocket watches: He plans to bequeath 21 watches to each of his children: Sarah, now 35, a documentary film producer who works for Ken Burns; Clara, 22, who is interested in urban education, housing and public service; and Max, 16, who loves history, politics and medicine. Botstein has been married to Barbara Haskell since 1982, and his two younger children are with her; she is a curator of early-20th-century art at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Both of Botstein’s parents served on the faculty of the Einstein College of Medicine in New York—his mother specialized in polio research and his father was a pioneering oncologist. They credited their survival to being physicians and encouraged their children to follow. But only Botstein’s sister, Eva Griepp, did. She is a pediatric cardiologist; his brother, David, is a microbiologist who directs the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton University.

Botstein’s mother, now 96, was struck when she was in her early thirties with bilateral Ménière’s disease, a disorder of the inner ear that causes distortion and hearing loss. To communicate with her more efficiently, the family created a language they called Botsteinese, a mixture of Russian, German, Polish, Yiddish and English that distilled the essence of their ideas into a few words. Botstein still speaks German and Russian.

The language-switching and his family’s failed attempt to convert him from left- to right-handedness intensified a stutter that lasted into Botstein’s early twenties. Through concentration and discipline he corrected it himself, but says that to this day public speaking requires more planning. But in public appearances he seems at ease. “Like all performances,” he says, “what seems easy is extremely practiced.”

Botstein hails from a rich Jewish heritage and an ardently Zionist background. His parents were not observant but helped found the Conservative Synagogue of Riverdale, New York, where his mother is still a member (his father died in 1994). An agnostic, he pays his dues to the Conservative Synagogue of Kingston, New York, “out of principle and respect for communal life.” Botstein is a proud secular Jew not ambivalent or defensive about his identity. In I Am Jewish: Personal Reflections Inspired by the Last Words of Daniel Pearl (Jewish Lights), he writes: “In Judaism, learning is prayer, for it celebrates the human capacity for language and thought.” He waxes nostalgic for the days of “exceptional Jewry,” arguing that “Jews have entered the indistinguishable middle class…. We are no longer the people of the book; we are a people of ordinary vulgarity. The real tragedy of American Jewry—and Israel—is that we’ve used privilege to become absolutely ordinary.”

Botstein himself has risen far above the ordinary, but he is not content to rest. “I don’t believe in the distinction between work and play,” he says. “I’m not the kind of person to take a vacation. I have no hobbies. I don’t work to live. I live to work.” H

Rahel Musleah’s Web site is www.rahelsjewishindia.com.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply