Arts

Exhibit

Theater

The Arts : Russian-Jewish Theater: Act I

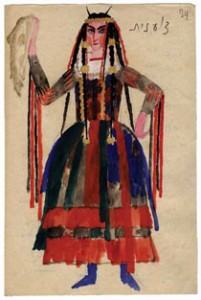

© 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

In the Soviet Union, plays and playhouses created by and for Jews thrived, and a traveling exhibition chronicles the artistry and the artists who sustained the dramas.

In October 1920, the Moscow State Yiddish Theater (known as GOSET, an acronym for its Russian name) opened an intimate new auditorium in a house on Bolshoi Chernyshevsky Lane, accommodating 90 spectators on benches. The walls, curtains and ceiling were theater in and of themselves, wrapping the audience in murals and paintings of upside-down acrobats, dancing actors, pirouetting directors, beheaded fiddlers, green cows, wedding couples and poetic muses, all set against vibrant geometric shapes and shafts of light and color.

The work was pure Marc Chagall—the celebrated artist had been commissioned to design sets and costumes for the inaugural production of three Sholem Aleichem works. However, he ventured radically beyond convention, and so the space came to be known as Chagall’s Box. New York’s Jewish Museum (212-423-3200;www.jewishmuseum.org) has re-created the experience in its exhibit, “Chagall and the Artists of the Russian Jewish Theater, 1919-1949,” which ran through March 22; the show will be on display at San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum (415-655-7800; www.thejcm.org) from April 25 through September 7.

The exhibition features more than 200 watercolors, oil paintings, drawings, posters, programs, costumes, set designs, musical scores, photographs and rare film footage from collections in Russia (primarily the A.A. Bakhrushin State Central Theater Museum in Moscow), France, Israel and the United States. Most have been hidden since 1949, when GOSET closed, and forgotten until glasnost in 1985.

According to the Jewish Museum’s senior curator, Susan Tumarkin Goodman, the artworks also serve as a window into Jewish experience under Soviet rule. Though Chagall left Russia in 1922 for Berlin and then France, his vision guided GOSET’s experimental, avant-garde approach, which blurred the boundaries between art and reality.

The centerpiece of the exhibition, Chagall’s 26-foot mural,Introduction to the Jewish Theater, depicts the artist’s perception of his own centrality: Chagall paints artistic director Abram Efros carrying him into the theater and introducing him to director Aleksei Granovsky. His palette is in his right hand and, as he gives his art to the world, the Ten Commandments emerge out of the left side of his head. The members of the company cavort across the canvas, which Chagall also filled with personal details: his family name on a pant leg; a portrait of his wife, Bella, and their child; his mother’s recent burial.

Four muses decorate the facing wall: Music—a green-faced fiddler on the proverbial roof, a boy floating above him; Dance—a buxom woman in a gray floral dress clapping her hands, with klezmer violin, trumpet and tambourine alongside her; Theater—a black-frockedbadhan, the wedding jester who mixed sorrow and joy in his entertaining, superimposed on a weeping bride and groom; andLiterature—a scribe ostensibly copying a Torah text, but the words read “once upon a time,” reflecting the importance of folklore over religion. A long frieze of a wedding feast stretches above the muses. The curtain design, Love on the Stage, is a Cubist swirl of dissolving clouds through which hints of a ballerina and her partner emerge: a lace tutu, a striped and stockinged leg.

While Chagall is undoubtedly the main course in this artistic feast, the exhibition integrates his work into the larger story of the Russian Jewish theater, its actors and artists. In fact, the show does not open with Chagall, though the mural, in an inner room, is immediately visible through three scrims. Instead, it begins with GOSET’s principal actor, Solomon Mikhoels. A portrait of Mikhoels by Natan Altman captures the energy and dynamism of the actor’s elastic yet simian face, and a one-minute video offers a foretaste of footage on display later in the exhibit—Mikhoels donning his crown for King Lear or sipping tea as the Sholem Aleichem character Reb Alter.

According to Goodman, the early days of the Russian Revolution not only allowed artistic expression but encouraged the Jewish theater. The Bolsheviks supported the efforts of minorities to establish cultural institutions defining their identities. The Jewish theater, which had its roots in Purimshpiels and was banned under the Czarist regime between 1883 and 1904, was reborn in two sharply different companies: the Yiddish-language GOSET, which focused on everyday reality, comedy, fantasy, even the grotesque, and successfully reached the Jewish masses; and the Hebrew-language Habima (“the stage”), which drew on folklore, tragedy and mystical tales and was committed to the Zionist dream. Together, they “represented the foremost expression of Jewish culture and identity in the Soviet Union,” Goodman writes in the accompanying catalog.

“Jews regarded [GOSET] as their home, their club, their synagogue, a place to [gather] and reminisce, a place to meet their friends…,” recalls Mikhoels’ daughter, Natalia Vovsi-Mikhoels.

“Habima sought in the mytho-poetic tales of the Bible a universal language that everyone, not only Jews, could understand,” writes Vladislav Ivanov, chairman of the theater department of the State Institute of the Arts in Moscow and author of two books on the Soviet Jewish theater. “GOSET, by contrast, was interested in precisely the disenfranchised shtetl existence that Habima was ashamed of and tried to forget.”

Artistically, the theaters revolutionized acting methods and theater design. The actors almost physically embodied the influences of Chagall, Altman, Robert Falk, Isaac Rabinovich, Aleksandr Tyshler and Ignaty Nivinsky, whose approaches included Expressionism (emphasizing emotion), Constructivism (focusing on form and structure) and Biomechanics (viewing the body as machine). Early-20th-century art critic Alfred Kerr noted that the actors “talk not only with their hands but almost with their hair, their soles, their calves, their toes.” The antinaturalist Chagall, who even put makeup on the actors, is famously said to have commented to Mikhoels: “Solomon, Solomon, if only you had no right eye I could make you up perfectly.”

Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, Moscow

The first galleries examine Habima’s two hits: The Dybbuk, S. An-ski’s story of Leah possessed by her betrothed, Chanan, to prevent her from marrying another; and The Golem, based on the legend of Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague who, to protect the Jews, created a powerful but destructive creature out of clay. From The Dybbuk, the white silk and cotton dress worn by actress Hanna Rovina, who played Leah, is displayed front and center. Behind it, a photograph shows Rovina in the same dress against the black-robed rabbinic court where Leah is taken to be freed of the spirit. Looped stills re-create the scene. Russian composer Joel Engel’s handwritten musical score for the “Beggars’ Song” is accompanied by the original soundtrack. Reinterpreted, the struggle of a soul against heaven and earth symbolized the social and cultural revolution against the old religious order.

Throughout the exhibition, Goodman ties together as many media as possible, pairing designs with photographs of their stage realizations. So Altman’s costume design for Freda, Leah’s nurse, with its orange-and-blue jacket and green skirt, contrasts with a black-and-white photograph of actress Tmima Yudelevitsch in a wide-hipped dress clutching a handkerchief. Altman’s geometric, kinetic and folk-inspired Cubo-Futuristic designs not only grace the walls; a photograph shows the very same drawings on the office wall of Habima founder Naum Tzemakh.

For The Golem, graphic artist Nivinsky let his imagination run wild. His fantastical preliminary sketches experiment with a bird golem in a tailed talit and black skullcap; a feminine fish golem with silvery scales; a robot-like frog golem; a nude, scarlet golem encircled by flames; and several hybrid golems, part animal, part human, part mechanical—one with a ram’s horn and black hat, another with a pink bird’s claw, a blue hoof and a blue tail poking out from a black robe. The only non-Jew who designed for the Jewish theater, Nivinsky revealed a profound knowledge of Jewish culture. Some of his work echoes drawings from the mystical 16th-century anthologySefer Raziel, reproduced in the popular Jewish Encyclopedia. An eerie set design of a ruined fortress where the Jews escape a pogrom combines Christian icons—a Madonna-like sculpture poses on a crescent moon—and Jewish symbols: a menora, lectern with an open siddur and Hebrew-lettered signs reading mizrah (east).

Though H. Leivick’s original script for The Golem describes a quest for the Messiah and what happens when an individual intervenes, Habima revised its symbolism as a metaphor for the Russian Revolution: a monster formed with the best of intentions. The allusion escaped the Russian censors, but not the Jewish audience.

In fact, while the Soviet government viewed the theater as an important propaganda tool, both Habima and GOSET often integrated illicit messages about the value of Jewish life, tradition and Zionism. However, Habima’s days were numbered: political and ideological clashes with the Bolshevik authorities caused the company to leave for Palestine in 1926. It eventually became Israel’s state theater.

GOSET was more adept at the political game. Its first production,An Evening of Sholem Aleichem, featured themes closely aligned with those of the revolution—bucking capitalism and religion as similar evils. Agents: A Joke in One Act, Mazel Tov and It’s a Lie!Dialogue in Galicia portray Sholem Aleichem’s recurring buffoon, Menachem Mendel, as he invests in foolish financial schemes. ForAgents, which takes place in a third-class train car, Chagall designed a white arch springing from the stage floor; a toy train chugs across it. His kitchen set for Mazel Tov incorporates familiar elements—a dreamy atmosphere, an upside-down goat. Hebrew letters on the fire screen spell out the beginning of the wordaleikhem.

Later, GOSET released a film version of four Menachem Mendel stories in Jewish Luck, a classic film with international distribution that satirized the dying traditions of shtetl life. A short video featuring four clips zeroes in on Mikhoels’s mischievous eyes and comedic antics; nearby hang Altman’s realistic pencil drawings, a poster advertisement and a cinema booklet borrowed from New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Goset did not shy away from productions that tested boundaries, adapting even the most outlandish themes to Soviet Realism. God of Vengeance, Sholem Asch’s explicit lesbian story, linked sinful behavior and capitalism in the antics of Yankel Tshaptshovitsh, a Jewish brothel owner, who tries to shield his daughter from immorality. Despite his efforts, she falls in love with a prostitute. Avrom Goldfadn’s The Sorceress: An Eccentric Jewish Playtransforms a melodrama thick with evil stepmothers, kidnapping, coincidences and magic into a critique of capitalism and early Yiddish theatrical tradition.

Rabinovich’s Constructivist stage design for The Sorceressfeatures a chaotic assemblage of platforms, steps, ropes and ladders that enabled the actors to perform wild acrobatics from level to level. The pure entertainment allowed audiences an escape from the restrictiveness and starvation that was the reality of 1920s Moscow.

With only a 1,000-word script, the entire effect of I.L. Peretz’s A Night in the Old Marketplace: A Tragic Carnival depended on the set, costumes and actors. The shtetl market turns into a graveyard as beggars, drunkards and prostitutes with their skirts split open are replaced by cadaverous counterparts who celebrate the wedding of a dead bride and groom. Mikhoels and Benjamin Zuskin play white-faced badhanim. Inspired by a visit to Moscow’s Institute of Forensic Medicine, Falk created zombie-like figures dripping flesh. A bony hand clutching the Hebrew letter pay, for “Peretz,” dangles ominously from the stage ceiling. The crumbling Old World pointedly raises the specter of the death of the shtetl.

The Travels of Benjamin the Third: Epos in Three Acts, based on a story by Mendele Mokher Seforim, continues GOSET’s critique of the shtetl and Zionism, although it secretly alludes to the benefits of living in the Land of Israel. A takeoff on Don Quixote, shtetlniksBenjamin and Senderl set out for the Promised Land only to wake up in the neighboring town: There is no place like their Soviet home. On the way, Benjamin has a dream filled with strange creatures and imagines himself married to the daughter of Alexander the Great. Falk’s costume and set designs throb with vivid eccentricity. In 1948, when Golda Meir attended a revival of the play during the first Israeli diplomatic mission to the Soviet Union, the government accused GOSET of a Zionist message.

Goodman uncovered some exciting finds for the exhibition. From the Russian State Documentary Films and Photographs Archives in Krasnogorsk she procured film footage of 200,000: A Musical Comedy, a 1923 GOSET production about Shimele, played by Mikhoels, a poor tailor who wins a lottery. A poster advertising The Tenth Commandment: A Pamphlet Operetta—the graphics, layout and Cyrillic fonts an art in themselves—is paired with a photo of GOSET members in front of the same poster, lent by Ala Zuskin-Perelman, daughter of Benjamin Zuskin.

GOSET’s success prompted the Soviet government to arrange a tour of Western Europe in 1928. In Paris, Chagall and Mikhoels met again, as documented in a photograph of the troupe at the artist’s villa. Granovsky defected to escape the repressive new Stalinist regime, and Mikhoels assumed the theater’s directorship, opting to perform “safe” classics such as Shakespeare. As Lear—probably Mikhoels’ greatest role—the actor channeled the egotistical and despotic king into a barely concealed depiction of Stalin tyrannizing his people; Zuskin played the Fool. Mikhoels’ wig and black robe are on display, as are Tyshler’s set design of a two-storied medieval castle and Expressionist watercolors. In a clip of the closing scene, as Lear lays dying next to Cordelia, he touches her forehead and kisses his fingers, replicating the gesture of kissing the mezuza. Mikhoels performed the role over 200 times in four years.

When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Mikhoels became the face of the Soviet war effort. The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee sent a fund-raising mission headed by Mikhoels to Jewish communities around the world. Photographs document his meeting with luminaries from Molly Picon to Albert Einstein to Paul Robeson; addressing 47,000 at New York’s Polo Grounds; and paying tribute at Sholem Aleichem’s grave in Brooklyn.

In 1948, after Mikhoels publicly voiced his support of a Jewish state, Stalin ordered his assassination—in the guise of a traffic accident. Thousands turned out in grief when his coffin reached the Moscow train station. The exhibition ends with the broken glasses found with his body (lent by his daughter).

Repressive Soviet violence almost obliterated the legacy of the Russian Jewish theater. In 1953, a suspicious fire damaged many drawings stored at the Bakhrushin museum. The charred borders of Rabinovich’s colorful designs for the Tshaptshovitsh apartment and the singed edges of a pencil drawing of Shloyme from God of Vengeance are even more potent because of their attempted destruction. Their survival—as well as that of the other artifacts in the exhibition—enable the dynamic canvas of the Russian Jewish theater to bustle with life once more. H

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply