Israeli Scene

Feature

Feature: Home Away From Home

Ismail Ahmed is one of the lucky ones.

He works 13 hours a day, 7 days a week, in his shop in Tel Aviv. Many of the people who provide him with most of his meager livelihood—private, English-language students—were just expelled from Tel Aviv by immigration police. And he pines for a home he doubts he will see again.

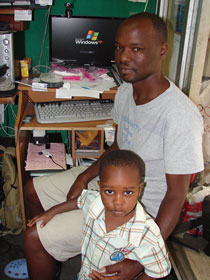

Ahmed (at right, with his son Kandar) can point to one stroke of luck, however, that makes all these worries trivial. “I am alive,” he says.

Many of the men from his village in western Darfur are not.

“Here we are together for the last time,” says the slim 43-year-old, pointing to a photograph of about 100 young smiling men and women lined up against a background of gentle green hills. “Only three or four of the men are still alive,” he adds, rattling off the causes of death: starvation, shooting, burning, torture.

The photo is displayed prominently on the wall of Ahmed’s shop in Neve Sha’anan, a rundown south Tel Aviv neighborhood where many Darfur refugees gravitated. Here, Ahmed runs his several-months-old computer repair and retail store and a night school where he teaches fellow refugees English and basic computer skills.

Ahmed is one of the unofficial leaders of his community. He is a cofounder of the Sons of Darfur, an organization that works with local and international bodies to assist refugees and draw attention to the situation in Sudan. As the group’s current vice president in charge of personnel, it is his job to interview and report on those in the community who need assistance with housing, education or health benefits; he is also in the middle of developing a Web site for the organization.

“The work he does is very valuable,” says Adam Abdullah, 43, general secretary of the Sons of Darfur. “If anyone in the community has a problem, they come to him.”

After working at odd jobs, Ahmed opened a business because it offered a degree of independence, a place for his children to hang out after school and, above all, a chance to help members of his community. “They can’t make anything of themselves if they don’t know English and computers,” explains Ahmed, who picked up fluent English and computer skills at church-run organizations in Khartoum and Cairo.

The shop became a one-stop support center for Darfur refugees, with Ahmed helping them find jobs and fill out refugee application forms. “He spends more time helping his people than he does doing business,” notes an American-born neighbor who works, for free, with Ahmed. “He’s a decent man—too good for his own good.”

Ahmed never imagined he would end up in Israel. His idyllic life in his village, growing sugar cane, mangos and guavas, was interrupted in the late 1990s when the Janjaweed, encouraged by government officials to grab land, swarmed down on his and other Darfur villages, burning Ahmed’s father alive, and jailing and torturing him.

Ahmed fled Sudan in 2003 with his wife and children, sneaking into Egypt, a country of fellow Muslims where he was sure he would be welcome. Instead, he encountered racism—“people in the street would call me ‘bushman,’” he recalls—and harassment. Buoyed by stories of a better life in Israel, he slipped his family across the Sinai border in June 2007. An Israeli Army patrol caught him, but released him in Beersheba.

Six months later, he became one of about 600 Darfur refugees given temporary residency, which entitles him and his family to health care, education, even a bank loan. “In Israel,” he says, “I have been treated kindly.”

He lives in a dilapidated two-room apartment with his wife, Alima, who works as a hotel cleaning woman, and children Amal, 17; Fatma, 6; Amin, 4; and Kandar, 2, who all attend local schools and kindergartens. (His oldest daughter is married and lives outside of Israel.)

Ahmed fears he may never return to the home and life he once had. “Maybe we will be like the Jews,” he says, “who never forgot their homeland and were able to go back only after centuries.” H

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply