Books

Books: Compassion, Speculation and Love

Fiction

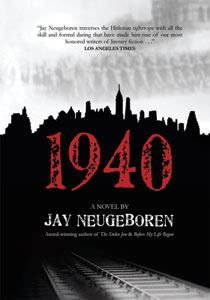

1940

1940

by Jay Neugeboren. (Two Dollar Radio, 274 pp. $15)

In his new novel, his first in over two decades, Jay Neugeboren has performed an astounding feat of literary alchemy, effortlessly blending science, history, religion, art, biography and psychiatry into a haunting tale that is at once a love story and a suspense novel. The narrative is based on an actual historical personage, Dr. Eduard Bloch, the Austrian Jewish physician who tended to Adolf Hitler’s family and was rewarded by the Nazi leader with an exit visa; his daughter and son-in-law had left for the United States some time before him. The story takes place in America, where the doctor remembers his past involvement with the Fuehrer’s relatives as he develops a complicated relationship with Elisabeth Rofman, a medical illustrator based at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

Much of the story is told in Bloch’s voice, through both his journals and his revelations to the talented and tenderhearted Elisabeth and her mentally disturbed son, Daniel. Elisabeth is caught up in a vortex of loss and anxiety; she came to New York to visit her aged father and discovered he has disappeared from his modest apartment in the Bronx.

She is also battling her Orthodox ex-husband, who is determined to have Daniel castrated. Her casual meeting with Bloch for medical reasons morphs into a complicity as they work in concert to help Daniel and support each other emotionally. That mutual support eventually translates into compassionate love.

Bloch, who initially faces condemnation for accepting favors from Hitler—and questions whether his actions were dishonorable—describes the care he gave to Hitler’s gentle mother during her horrific struggle with cancer and how Hitler changed from a devoted son and caring brother to his mentally disturbed sister into an embittered mass murderer.

It is a tribute to Neugeboren’s skill that he manages to humanize the dictator without minimizing the horrendous evil of his intent.

In 1940—the year that gives this insightful novel its title—the world was inching toward a disastrous war that would test civilization itself. Elisabeth, artist, fiercely protective mother and sensual lover, and Eduard, intuitive intellectual, friend and companion, are exemplars of cultivated civilization, of uncompromising humanity. The history that threatens to overtake their lives will not defeat them.

At book’s end, they prepare to celebrate the approaching Sabbath together with “candles, challah and a bottle of wine…hopeful that when it begins, in a few hours, at sundown, peace will descend upon [them].”

—Gloria Goldreich

Light Fell

by Evan Fallenberg. (Soho Press, 229 pp. $22)

The title of this novel has at least two meanings: One is a talmudic reference, quoted with a homoerotic interpretation by one of the characters. The second refers to the predicament of the protagonist Joseph Licht, whose last name means “light.” Joseph, an Orthodox, married Israeli and struggling academic, falls in love—and disgrace—at once. The object of his passion is a man, a famous rabbi, no less. His indignant community shows him no forgiveness, and he is banished from his home, leaving a heartbroken wife and five young sons.

We meet Joseph 20 years later, now living in a luxury Tel Aviv high-rise, cooking a gourmet meal in anticipation of the arrival of his children for his fiftieth birthday party. As he waits anxiously, still aching for their acceptance, Joseph thinks back to the ill-fated affair that was both the most sublime, liberating and soul-affirming experience of his life, and a disaster for many others.

In this debut novel, Fallenberg, who has translated the works of some of Israel’s leading authors from Hebrew into English, gives us a taste of his own elegant prose. With his sensitive ear he contributes to an emerging body of English-language fiction from Israel, deftly conveying the flavor of the country’s ambiance, culture and even language. In the tradition of American Jewish writers, such as Lev Raphael and Aryeh Lev Stollman, Fallenberg explores the painful tension between religious observance and unsanctioned sexual desire. He offers the English reader a rare glimpse into contemporary Israeli life through engaging characters.

Although this novel takes on one of Orthodoxy’s biggest taboos, it is mostly a personal odyssey focusing on the anguish of an individual whose longings are at odds with social norms and religious doctrine. The protagonist and those touched by his life wrestle with their conflicting loyalties, struggling to find meaning and dignity in a complex world.

—Shoshana London Sappir

Dropped From Heaven: Stories

by Sophie Judah. (Schocken Books, 256 pp. $23)

Sophie Judah has used the “write what you know” guideline to interesting effect in her debut work of fiction. A member of the Bene Israel—the 2,500-year-old Indian Jewish community discovered by Iraqi Jewish traders in the 18th century—Judah has based her 19 short stories, which take place from 1890 to the present, in India’s mythical Jwalanagar region.

Thus, Dropped From Heaven is automatically of historical and sociological interest. The fascination with an exotic Jewish culture whose roots are unclear initially sweeps the reader along. But that interest takes us only so far. The stories have charm, and many move or amuse us. But Judah’s writing is dry, even awkward, at times resembling journalism or spontaneous storytelling (without self-editing) more than fiction. Judah may develop the literary devices for effective fiction, but she doesn’t have them yet.

Where the writer succeeds is in finding the universal in the particular. There’s more that binds us to the Bene Israel than common rituals or ancient history. In Jwalanagar, parents quarrel with children, young people fall in love—not always according to the rules—and women fight for freedom from tradition. We may not know the kind of violent religious conflict that existed between the Muslims and Hindus in prestate India, but we can understand the region’s early history.

While the lives of the Bene Israel were blessedly free of persecution and anti-Semitism, they have been beset more recently with political-religious upheaval brought about by modernity and the rise of the State of Israel. Once 20,000 strong, the Bene Israel community “lost” three-quarters of its numbers to aliya—the author and her family among them.

All these forces—especially the clash of modernity with tradition and intergenerational conflict—find expression in Judah’s stories. In “My Son, Jude Paul,” a priest who raised a Jewish boy is pleased by the child’s devotion to Christianity but troubled that the young man lacks respect for his biological father. In “Hannah and Benjamin,” a young woman’s parents object to her boyfriend because his position as lecturer at a Hindi college seems too lowly; what they don’t bank on is her stubbornness in defending him.

In the heartbreaking “Her Three Soldiers,” a mother who has lost all her sons finds solace in insanity—and a myth of heroism. A different kind of motherly love underlies the humorous title story.

A few of the stories, including “The Courtship of Naomi Samuel,” involve young Israelis of Bene Israel background who return to India. These tales capture the love of Zion contrasted with the sadness of a dwindling community.

Judah has plenty of material. One hopes her next book will focus more on style.

—Barbara Trainin Blank

Nonfiction

Operation Exodus: The Inside Story of American Jews in the Greatest Rescues of Our Time

by Gerald S. Nagel. (Contemporary History Press, 274 pp. $36)

Israel’s heroic beginning, which saw gradual resettlement by several pioneering generations and a triumphal entrance on the international stage as an independent Jewish nation, is long over. In the past two decades, both on the field of battle and in the arenas of regional and international diplomacy, the country’s record has been, well, spotty. In contrast, Israelis look on the arrival and absorption of over one million Jews from the former Soviet Union since 1989 together with the rescue of over 40,000 Ethiopian coreligionists in 1980s and early 1990s (Operation Solomon) as shining hours that not only burnished a tarnished self-image but rekindled the country’s founding mandate as a Jewish state.

When Israelis think of the role of the diaspora in connection with these exploits of Jewish liberation—which is not very often—they tend to relegate it to auxiliary status. Nevertheless, when Israelis confront the diaspora, the accompanying tone of condescension is not only gratuitous and unhelpful but regrettable. As author Gerald Nagel demonstrates in Operation Exodus, the response of American Jewry to appeals for funds to carry out these missions was immediate and generous. This book provides an insider account of the truly substantial part played by American Jewry in what Nagel calls, with considerable justice, the “greatest rescues of our time.”

Nagel, who died last year, served for a dozen years as the chief communications officer of the United Jewish Appeal. In such capacity, he was the point man in choreographing the abundant love and cash from America to Israel. Without these, the operations simply could not have been executed nearly so smoothly.

Nagel’s narrative focuses primarily on celebratory scenes such as “The Breakfast of Champions” at New York’s Hotel Regency, which he dreamed up in 1990. Over lox and bagels, Jewish millionaires such as Laurence Tisch and Marvin Lender, together with 57 others, contributed $1 million or more a plate to the cause of liberating Russian Jewry. Indeed, Nagel relishes recounting personal stories about these and other philanthropists whose generosity exceeded all precedent both in New York and at similar functions from Miami and Baltimore to Chicago and San Francisco.

Equally important, however, Nagel does not neglect to point out that Jewish millionaires weren’t the only ones who responded to the moment. Over a period of four years, “1.2 million Americans, overwhelmingly Jews but not only Jews, contributed $882.9 million.”

If Operation Exodus is not elegantly written, it nevertheless offers a valuable trove of raw data about how the diaspora rose splendidly to assist Israel in meeting its obligation to Jews in distress. Fund-raising may not strike one as a heroic profession, but at his chosen calling Nagel was not only a brilliant tactician but demonstrated passionate support for the State of Israel. Especially for Israelis, Operation Exodus could serve as a useful corrective to self-absorption.

With Nagel’s passing, Israel mourns a Jewish soul whose contribution to its welfare was both massive and timely.

—Haim Chertok

Lost Communities

A Goldmine of Culture and History

The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe,

edited by Gershon David Hundert. Two volumes. (Yale University Press, 2,448 pp. $400)

Only after the Iron Curtain was lifted about 20 years ago, giving access to archives and libraries as well as population records in the former Soviet bloc, was it possible to research and finally publish this unprecedented reference work on the history and culture of East European Jewry—including today’s Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Poland, the Baltic States and Finland, Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus and Russia.

With 1,800 entries, over 1,000 illustrations (57 in color) and 55 maps, this huge work covers everything from art, literature, folklore and architecture to music and theater. Topics include amulets and angels; the emergence of anti-Semitic parties and movements in the second half of the 19th century; assimilation; Hasidic dynasties; and lists of Web sites for general and national archives.

Some of the 450 contributing experts are Elisheva Carlebach on Shimon Abeles, a youth in Prague whose father was accused of his murder because he had expressed interest in converting to Christianity in 1694; Dan Miron on Mendele Moykher-Sforim, father of modern Hebrew and Yiddish prose (1835-1911), born in Belorussia; Dan Laor on Shmuel Yosef Agnon (1888-1970), Galician-born Nobel laureate in literature who lived in Jerusalem; Steven J. Zipperstein on Zionist thinker Ahad Ha-am (1856-1927), born Asher Ginzberg in Ukraine; and Arthur Green on Elimelekh of Lizhensk (1717-1786), Hasidic founder in Galicia and Poland.

This treasure trove of information gives new life to bygone worlds.

—Zelda Shluker

Top Ten Jewish Best Sellers Editor’s Note: Jewish readers purchase books for enjoyment and enlightenment, to reinforce their viewpoints or to see what the opposition is saying. The Top Ten Jewish Best Sellers list reflects only sales and does not imply approval by Hadassah Magazine—or the people buying the books. Courtesy of www.MyJewishBooks. com; titles selected based on sales.

Top Ten Jewish Best Sellers

FICTION

1. Moscow Rules, , by Daniel Silva. (Putnam, $26.95)

2.The Yiddish Policemen’s Union: A Novel, by Michael Chabon.(HarperCollins, $26.95)

3. Certain Girls: A Novel, by Jennifer Weiner. (Atria, $26.95)

4. People of the Book, by Geraldine Brooks. (Viking, $25.95)

5. City of Thieves, by David Benioff. (Viking, $24.95)

NONFICTION

1. The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible, by A.J. Jacobs. (Simon & Schuster, $25)

2. The Zookeeper’s Wife: A War Story, by Diane Ackerman. (W.W. Norton, $23.95)

3. Night, , by Elie Wiesel. (Hill and Wang, $9, paper)

4. When a Crocodile Eats the Sun: A Memoir of Africa, by Peter Godwin.(Back Bay Books, $14.99)

5. Getting Our Groove Back: How to Energize American Jewry,by Scott A. Shay.(Devorah, $24.95)

Editor’s Note: Jewish readers purchase books for enjoyment and enlightenment, to reinforce their viewpoints or to see what the opposition is saying. The Top Ten Jewish Best Sellers list reflects only sales and does not imply approval by Hadassah Magazine—or the people buying the books.

Courtesy of www.MyJewishBooks.com; titles selected based on sales.

Books in Brief

Undiscovered,

by Debra Winger. ((Simon & Schuster, 188 pp. $23))

Debra Winger largely disappeared from Hollywood in recent years to raise her two sons and ponder the future. Her most detailed expositions explore her Jewish identity, including her relationship with a strictly observant grandmother, pride and anxiety about her oldest son’s bar mitzva and apprehension about visiting Germany.

—Adam Dickter

Jewish Sisters in Sobriety: Jewish Women’s Untold Stories of Alcoholism, Drug Addiction, Co-Dependence and Recovery,(JACS/Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, 191 pp. $15)

The stories compiled by JACS are unlike any other collection of Jewish women’s experiences. The bad news: Jewish women, strictly religious or secular, single or married, are just as likely to be addicts as men or non-Jews. These stunning stories (and resource list) not only reveal shattered women’s lives, but also give hope for healing.

—Susan Adler

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply