Issue Archive

The Arts I: A Nation in Focus

A range of recent books and exhibitions showcases photography depicting intimate moments and iconic scenes from Israel’s history.

“Israel,” writes the country’s former prime minister and current president, Shimon Peres, “is a drama no less than a nation.” To reenact that drama with all its triumph, truth and tragedy, a number of exhibitions and books celebrating the state’s 60th anniversary focuses on images that depict, scene by scene, Israel’s inception and evolution. The resonating themes spell out the headlines of a continuing story of heroism and sacrifice, of pioneers and soldiers, immigrants and leaders and ordinary men, women and children.

Peres’s words are part of his foreword to David Rubinger’s memoir, Israel Through My Lens: Sixty Years as a Photojournalist(Abbeville Press). Winner of the Israel Prize for services to the media and a correspondent for Time Life, Rubinger, 83, emigrated from Vienna to British Mandate Palestine in 1939 and grew up along with the state. The book’s 129 photographs—most in black and white—offer an encyclopedic sweep that includes the iconic and the intimate. What could be more emblematic of Israel’s victorious spirit than Rubinger’s signature shot—three paratroopers gazing at the Wall they had just helped liberate during the Six-Day War—or reflective of its maturity, when Rubinger photographed the men 30 years later in the same pose?

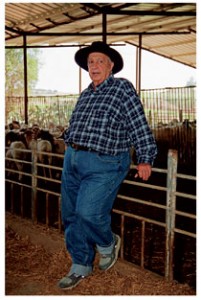

What could be more revealing than the quiet portraits of Golda Meir in a flowered apron from 1956; Menahem Begin helping his wife, Aliza, put on her shoe (1980); Yitzhak and Leah Rabin at breakfast (1994); or Ariel Sharon in plaid shirt and jeans at his Negev ranch (2000)? The tragedies Israel confronts with unbearable regularity are mirrored in the embrace a woman gives a child amid the rubble of a Syrian mortar attack (Kibbutz Gadot, 1967) and the tear-and-dirt- streaked face of a Palestinian girl standing near the bulldozed ruins of her house (1969).

Rubinger finds humor amid the somberness: In 1956, an Israeli officer, French commandant and three nuns from Jerusalem’s Notre Dame Hospital search no-man’s land intensely. Their goal? To find a patient’s dentures, which had fallen from the hospital window. Another picture shows Sister Augustine’s ecstatic face when she finds them.

But terrorism and war are just over the horizon. After a grenade attack on the Knesset in 1957, David Ben-Gurion is wheeled into the operating room at Ziv Hadassah Hospital; a nurse during the Yom Kippur War cares for a wounded soldier (1973); Palestinians throw stones at a helicopter (the first intifada, 1988).

Rubinger lays the whole story before us, private and public moments, in peace and at war. His photographs and commentary are also available as a documentary film—Eye Witness, David Rubinger, directed and written by Micha Shagrir (www.shipuz.com).

Yet this pictorial journey really starts a century earlier, when pioneering photographer and Anglican missionary James Graham and his protégé, Mendel Diness, a convert from Judaism, trained their cameras on 1850s Jerusalem. “Picturing Jerusalem, James Graham and Mendel Diness, Photographers” began as an exhibit at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, was then at the Yeshiva University Museum in New York and is scheduled to travel back to the Israel Museum (date uncertain). In this show, available in catalog format, the central characters are places rather than faces: the city’s exterior walls in silhouette; its rugged gates, domed mosques and monuments; the sparsely settled mountains and valleys that echo with biblical footsteps.

The photographers enveloped the city in a “sacred aura” and offer an insider’s authenticity, writes Nissan N. Perez, senior curator at the Israel Museum, in a catalog essay. Diness, a watchmaker by profession, was forced to learn a different trade when his Jewish clientele boycotted his shop after his conversion. The catalog presents his and Graham’s photographic visions side by side: Often, they shot the same view from the same angle and time of day.

“Diness displays a fresh, almost childlike perception rather than the sophistication that results from experience,” writes Perez. “In many cases the immediacy of his work is the result of moving in closer and focusing on the subjects he found most interesting, whereas Graham’s concern for composition led to more artistically balanced and therefore somewhat more distant images….”

It is almost impossible not to do a then-and-now comparison. The vibrant modern neighborhood of Mishkenot Sha’ananim, for instance, was once little more than a windmill. Vertical views of the Western Wall from Graham and Diness convey a timeless majesty, a lone supplicant leaning against its stones. Through Rubinger’s lens, 150 years later, Pope John Paul II is that lone supplicant, his head bowed.

New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage–A Living Memorial to the Holocaust highlights the years leading up to independence through the eyes of Rubinger’s older colleague in “‘To Return to the Land…’ Paul Goldman’s Photographs of the Birth of Israel,” on display through May 11. Goldman, a Hungarian-born photojournalist who immigrated to British Mandate Palestine in 1940 at the age of 40, died in 1986 virtually forgotten. In 2000, on a hunt for a photo of Ben-Gurion doing a headstand, Rubinger remembered the image was Goldman’s and uncovered 40,000 negatives in the attic of the Goldman family home in Kfar Saba. Rubinger helped arrange for philanthropist Spencer Partrich to purchase and preserve the collection; the museum chose 44 images for this exhibit (40 more appear at an audiovisual station).

The show’s title, drawn from the original words of “Hatikva,” deals with the varied valences of returning to the land, says Louis D. Levine, director of collections and exhibitions at the museum and the exhibit curator. A 1940s kibbutz series details the primitive huts erected in early settlements from the Negev to the Lebanese border. Life was hard: Workers irrigate vineyards barefoot, spreading manure in the fields, pitchforks outlined against the sky, the wheels of their mule-pulled carts encrusted with mud (Kibbutz Ramat Yohanan). Yogurt and date jam was a breakfast treat (corn harvesters at Kibbutz Ashdot Ya’akov), and at meals, each person was rationed half an egg. Yet the devotion to the land was unquestioned.

The photos are animated by fascinating quotes Levine gathered from memoirs and interviews. In one, Rubinger describes his worst kibbutz job: For a week he had to bring cow urine to the compost heap. “It was carried in big tins and covered with a sack, but it was in a mule-drawn cart on an uneven road. You can imagine, for that week no one wanted to sit near me at the dining hall.”

The land’s urban areas bore little resemblance to today’s bustling cities. Egged buses, Arabs on donkeys, vendors selling corn on the cob, Yemenite Jews and Orthodox women in sheitels mingle against Bauhaus architecture. On V-E Day, a sea of people celebrated on the streets and rooftops; Israeli journalist Didi Menussi recalls being “so insane with joy that we took the tables out of the café, made a bonfire out of them and danced the hora.”

Interestingly, there is no image of festivities on the 29th of November, when the United Nations voted to declare Israel a state, probably because that was the day Goldman’s daughter was born. At Ben-Gurion’s suggestion, he named her Medina (Hebrew for state).

But the land was also the scene of painful birth pangs, mostly in battles against the occupying British, as seen in images from 1946. The King David Hotel, which served as British military headquarters, is blown up by the Irgun, claiming 91 lives; British soldiers shoot and kill Irgun and Haganah members. In a stark contrast to today’s tanks, guns and military high tech, Jewish auxiliary policemen in fezzes and on horses patrol Arab villages.

And here, famously, is the climax we anticipate: The photo of Ben-Gurion standing below a portrait of Theodor Herzl (May 14, 1948). “The State of Israel has arisen!” he declared. “This meeting is over.”

The joy is tempered by reality: “I don’t think there were any celebrations,” recalls Moshe Dayan’s wife, Ruth. “So many were killed by May, all between 18 and 20 years old.” The new state was peopled by refugees, smuggled in by ship from Eastern Europe (“Jewish State,” 1947), airlifted from Yemen (1949) and brought from other Arab countries. Israel created its own refugees as well: Arabs expelled from their village snake across the fields (1945). The exhibit ends with a triptych of Ben-Gurion, a follower of the Feldenkrais Method, doing a headstand on Herzliya beach (1957)—the image Rubinger was searching for when he discovered Goldman’s photos.

“Israel: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow” at the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage in Cleveland picks up almost where Goldman ends. In 60 images for 60 years, the show salutes the work of photographers from the cooperative international Magnum photo agency; the exhibit runs through June 29. (Organized by art2art Circulating Exhibitions, the exhibit will next travel to Utah’s Temple Har Shalom in Park City; 435-649-2276;www.templeharshalom.com , through October 9; and from mid-October through the end of December at the Salt Lake City and County Building; for more information, contact Hava Gurevich, director of art2art, 914-725-1045; www.art2art.org .) Some images overlap naturally with Goldman’s and Rubinger’s: Robert Capa’s photo of Ben-Gurion declaring statehood; images of aliya and war. The immigration continues, expanding the country’s diverse profile: Thomas Hoepker captures an Ethiopian woman and a Hasid at a bus station (1964); Micha Bar Am photographs Russian Jews boarding a plane to Israel in darkness (1990).

Life assumes a normalcy with its secular and religious textures. An Auschwitz survivor in a talit katan carries a plank of wood on a moshav (Capa, 1949); a man exultantly holds up his newborn daughter swaddled in white, the first child born on the settlement of Alma (David Seymour, 1951). Girls in white pinafores sew and read patterns at a Hadassah-sponsored girls fashion school (Burt Glinn, 1957). Defense is part of everyday life: A woman prepares for sentry duty, a rifle slung over her shoulder (Seymour, 1951). At a 1952 wedding, guns and a pitchfork are improvised poles that hold up a huppa (Seymour). An Israeli family dons gas masks during the Gulf War (Bar Am, 1991).

The same stone buildings and domes from the time of Graham and Diness appear in these photos—but they are now under Israeli protection. The Kotel is transformed into a symbol of freedom. Only a soldier’s leg, hand and rifle are visible in Marc Riboud’s view of a guard post overlooking the Old City (1973).

Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion Museum in New York foregoes a panoramic overview of history to focus on one critical moment in “10.6.73– The Yom Kippur War: Photographs by Thomas Heyman.” The exhibit, through July 11, displays 200 black-and-white images of Hativa Sheva, the 7th Brigade of the Israel Defense Forces, which fought on the Syrian front. Unprepared and undermanned, their tenacity and courage won a military victory at a terrible cost.

Heyman, a New York-born photojournalist, immigrated to Israel in 1970 and was living in Safed with his wife, Uziela, when the war broke out. They turned their home into a relief center, and at age 45, Heyman was invited to join the brigade as its official photographer. “Every day I would photograph the soldiers in battle,” he recalls. “[I] tried to record the faces of young men growing old.”

On a wall of portraits almost like yearbook photographs, it is the men’s youth that stands out. There is a teenager with wavy blond hair and an Ethiopian boy next to him. Some wear sunglasses, wool hats or helmets; some smile; others are pensive and exhausted.

“In an instant,” says curator Laura Kruger, “you get their personalities. You feel their fear, fatigue, optimism, camaraderie….” And many perished in the war.

,p>Heyman donated his photographs and negatives to the IDF archives, which released them for the exhibit along with battle maps and a tattered brigade flag that Heyman had rescued.

“This is a microcosm of Israel’s vulnerability,” says Jean Bloch Rosensaft, senior director of public affairs at HUC-JIR. “Today we identify Israel as a bulwark of power and stability in the Middle East, but this exhibit evokes the fragility of Israel that was— and is—the reality of its existence.”

In a couple of poignant photos, faces are not even visible: Two tank drivers, their heads down, pick at pebbles despondently; and two soldiers, photographed from behind, link arms—buddies, brothers, comrades. A vertical line of stitches down the middle of the chest of a recovering soldier reflects the price of battle.

“There are moments of…reckoning and loss,” says Rosensaft. “There is no idealization, yet there is a sense of hopefulness and confidence. It gets at the heart of personal commitment that enabled Israel to reach 60 years.”

Little has changed, she notes. “The integrity and honesty of the photos,” Rosensaft adds, “can teach us about Israel’s unending search for security and peace; they can bring us back to who we are and what Israel means.”

In contrast, “Celestial Nights: Visions of an Ancient Land; Photographs by Neil Folberg” depicts magical landscapes detached from politics and war. At the Yeshiva University Museum until August 24 and available in book format (Abbeville Press), Folberg’s images open up vast skies and fathomless vistas (“Kanaf & Kineret”) and focus on fig trees, ancient ruins and cacti bathed in light. The darkness itself is tactile: In “Amudei Amram,” craggy mountains are almost indistinguishable against clouds giving way to sunrise. Folberg’s awe-inspiring world, devoid of human forms, summons the psalmist’s understanding of the grandeur of heaven and earth.

Folberg uses high-speed infrared film and digital imaging to reconstruct images. Though skies and landscapes are real, the result could be pure imagination, he writes in the companion book, adding that his work sometimes captures what he saw and photographed; sometimes what he saw but could not photograph because of technical limitations; and sometimes what he wished to have seen.

“Perhaps this is the metaphor of these photographs: the horizon between knowledge and imagination, between the present and eternity, between substance and spirit, certainty and doubt,” he writes.

Against the backdrop of the journalistic and historical exhibitions, Folberg’s work echoes images and evokes questions. Did the soldiers in the Yom Kippur War feel the breathy whisper of “Wind, Golan” in their tanks?

In Folberg’s “As a Dove,” the interplay of light and darkness casts a dove-like illumination on the landscape. Startling in its similarity is Bar Am’s 1977 “Peace Dove”; the photo shows a worker carrying a wooden bird to the site where the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty was to be signed.

Maybe it is not a coincidence that our prayer for Israel remains eternal and constant. Appropriately on Israel’s 60th anniversary, Folberg connects the land to its ancient promise—that Abraham’s descendants should be as numerous as the uncountable stars in the sky.

On Exhibit and in Print

- “10.6.73–The Yom Kippur War: Photographs by Thomas Heyman,” Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion Museum in New York, 212-824-2205;www.huc.edu/museums

- “Celestial Nights: Visions of an Ancient Land; Photographs by Neil Folberg,” Yeshiva University Museum in New York, 212-294-8330;www.yumuseum.org

- Israel Through My Lens: Sixty Years as a Photojournalist, by David Rubinger with Ruth Corman (Abbeville Press)

- “Israel: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow,” Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage in Cleveland, 216-593-0575;www.maltzjewishmuseum.org

- Picturing Jerusalem, James Graham and Mendel Diness, Photographers, by Nissan N. Perez (Israel Museum)

- “‘To Return to the Land…’ Paul Goldman’s Photographs of the Birth of Israel,” Museum of Jewish Heritage–A Living Memorial to the Holocaust in New York, 646-437-4200;www.mjhnyc.org

Also on Display

- “Israeli Women: A Portrait in Photographs” explores the evolving faces and roles of women in the Jewish state from before 1948 to modern times through 63 images from 18 photographers. At the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles through August 30; 310-440-4544; www.skirball.org

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply