Issue Archive

The Arts: From the Creative Depths

Musician Idan Raichel and his band have distilled the sounds of Israel’s disparate cultures into unique music with an international appeal.

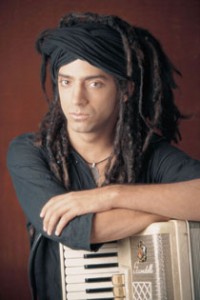

It is just before show time and Israeli musician Idan Raichel bends slightly and peers into a full-length mirror. He gathers long, stray dreadlocks in each hand, ties them behind his head and walks toward the stage.

Since his spectacular rise to success over the past four years, Raichel and his band, The Idan Raichel Project, have won over audiences of tens of thousands in New York, London, Paris, the Far East and Africa. Tonight, however, they are performing at an upscale bat mitzva party in Israel, in Herzliya.

On stage, Raichel, as usual, sits off to the side with his keyboards, giving center stage to his three singers. Two of them are Ethiopian—Cabra Casay and Wagderass (Avi) Vese—and all are barefoot and dressed in black.

They launch into one song after another, as the 12-year-olds sing along, between screams, and their parents sway in the background.

The energy of the music and the performers permeates the room, creating the same kind of magic felt at Raichel’s bigger shows. Between sets, he connects with the kids, telling them how embarrassed he was when he had to play the accordion—an instrument he started playing when he was 9—at his own bar mitzva.

The idan raichel project is an innovative work-in-progress that incorporates the talents of 70 musicians in recordings that represent the vast ethnic tapestry of Israel today. The Project is a celebration of the Jewish diaspora come home, a blending of the gutturals of Morocco with the gentle repetitive consonants of Ethiopia, biblical poetry and modern street Hebrew.

Among the scores of contributors are young artists such as Sergio Braams, who brings Caribbean sounds to the Tel Aviv music scene, and Israeli Arab performer Miri Anwar Awad. Raichel, who composes and writes the band’s music, has also included icons of Israeli music in his work, such as the late beloved Yemenite singer and actress Shoshanna Damari.

The Project’s music hit Israel at the end of 2002, inundating the airwaves with its funky, contemporary dance beats and synthesized sounds.

The first album, The Idan Raichel Project, went triple platinum (150,000 copies sold) and had four No. 1 singles, such as the Ethiopian-inspired “Bo’ee” (“Come with Me”). Something in these songs dug right down into the hearts of Israeli listeners and made them want more.

Americans—both Jewish and other—were not far behind; the Project was the first Israeli band to perform at the famed Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York. Fans pack concert halls and form long lines for autographs after shows of the band’s American tours.

“The Idan Raichel Project is one-of-a-kind,” says Or Celkovnik, chief music editor of Galgalatz, Israel’s premier pop music radio station. “It became an Israeli classic the moment it was released.”

The Project’s follow-up album, Mi’Ma’amakim (Out of the Depths), released in 2005, made gold two days after its debut. Damari, who passed away in 2006, sings on two of the album’s cuts, both written by Raichel; they are her final recordings. The album’s title song, taken from Psalms, is a modern day Song of Songs combined with excerpts from a traditional Ethiopian chant, “Nanu Nanu Ney.” Its haunting groove combines lyrics about love with images of nature, though Raichel replaces deer and vineyards with rivers, fields, the sky and the sun:

Who’ll lend his hand to build you a home/ Who’ll lay his life down under your footsteps/ Who like the earth at your feet shall live on/ Who’ll love you better than all of your lovers/ Who’ll save you from the rage of the storm/ Out of the depths. In November 2006, the Project released its first international album, also called The Idan Raichel Project, on the Cumbancha label, a division of Putumayo (see review, page 46). The New York Times chose the CD as one of seven top world music releases for 2007.

Raichel, 30, is simultaneously energetic and mellow. With his dreadlocks, head scarf and big blue eyes, he looks like a cross between a Rastafarian and an Afghani tribesman. He is excited about the Project’s first international release and speaks in the third person plural when referring to the band.

“It’s a big challenge for us to perform to a worldwide audience,” he says. “But after these four years, we are becoming a picture of the Israeli melting pot that we can be proud to present all over the world.

“I’m very proud that we cooperate with singers such as Mira Anwar Awad. She’s got her opinion about the Israeli-Arab conflict, but it doesn’t matter because at the end of the day, we are making music.”

Raichel’s music is heart-stoppingly beautiful and the words sheer but accessible poetry. In his shows, Raichel plays keyboards and sings. Seven other band members accompany him with vocals and on guitars, drums, bass, oud and percussion. His first hit single, “Bo’ee,” which everyone in Israel has been singing since 2003, has, like most of his songs, simple but moving lyrics:

Come with me/ Take my hand and let’s go/ Don’t ask me where to/ Don’t ask me about bliss/ Maybe it will also come/ When it comes,/ it will pour down on us like rain.

The lyrics came to Raichel as he was lying on a mattress in his studio just after he had broken up with a girlfriend. Before and after each verse, there is a compelling and mysterious chorus in Amharic:

Hear me, my Homeland/ In the night, in the mud/ Hear me, my Homeland/ When you fall off the horse/ Hear me, my Homeland/ My brother, don’t get angry/ Hear me, my Homeland/ No one has seen you/ Hear me, my Homeland/ Better be careful/ Hear me, my Homeland/ May all your days be good….

Band member Rony Iwryn, a percussionist who immigrated to Israel from Uruguay 23 years ago at the age of 18, has been playing with Raichel for a year and a half. He seems to speak for the entire band when he says, “I’m really enjoying myself. I love the music Idan writes and the room he gives [us] musicians to express ourselves in the performances. As a percussionist, that is very important.”

Raichel’s talents are prodigious. His blend of the musical traditions of Israel has created a modern Israeli aesthetic that appeals to people around the globe.

“Idan Raichel is Israel’s No. 1 music export in the United States right now,” says David Brinn, music critic for The Jerusalem Post. “He’s managed to combine Western pop with a Middle Eastern style. It’s very tribal. Very danceable. Also, the visual aspect of beautiful Ethiopian singers and his Afghani look is very exotic.”

“I know people who don’t know Hebrew, who are non-Jews and not Israeli, who heard it and felt something and wanted to hear more,” says Celkovnik.

Chicago filmmaker Jay Shefsky and his wife, physician Liz Feldman, heard The Idan Raichel Project live. “Our 17-year-old daughter, Hannah, introduced us to him,” says Shefsky. “We went to his concert in Chicago, and it was amazing. He is the perfect intersection of Hannah’s love of Israel, her interest in world music—and her fondness for dreadlocks.” Israelis like not only his music, but Raichel himself.

“He seems nice. Modest. Not so full of himself like other famous singers,” says Naomi Rottman, a young medical secretary in Israel.

Raichel often performs at benefit concerts and recently returned from a trip to Africa with the Israeli medical nongovernmental organization, Save the Heart of a Child, which brings third-world children in need of life-saving heart surgery to Israel for the procedure.

Still, Raichel works to not let the success go to his head. “You just have to fix it in your mind that if people come to you and say they love you, you know you have to not get drunk from love because it’s obvious that it’s something very temporary which can come and go,” he says. “I had…luck that people find themselves close to my music at this time, but you know, there are many examples of great artists who didn’t have the luck to be beloved in their own lifetime. So it’s good to keep it in proportion.”

And he doesn’t take all the credit. In the liner notes of his first CD, Raichel’s first thank you is to “God who has blessed me.”

He adds, “I think that God maybe sees [my music] in this time as an important message.”

A third-generation sabra of east european descent, Raichel grew up in Kfar Saba, near the center of the country and displayed an interest in world music from a young age. During his Army service, he joined the Army rock band, which toured military bases performing covers of pop hits. He was introduced to Ethiopian sounds while working as music director in a boarding school with many Ethiopian students. He began exploring the music in Ethiopian clubs, bars, synagogues and weddings. Raichel brought Ethiopian musicians into the studio he set up in his parents’ basement, blended their words, chants, tunes and instruments into his own songs and put together a demo tape, thinking it would help him get producing jobs.

As soon as Gadi Gidor of Helicon Records, one of Israel’s biggest record labels, heard the tape, he knew he had a hit on his hands. “All of a sudden there was a light put on [Ethiopian] culture, this small wonderful culture living among us, which not many people in Israel had come across. It had social and artistic significance,” he said in an interview printed in the San Francisco Chronicle. Helicon decided to release the demo as an album.

Raichel says he didn’t expect the huge, instant success: “It was a big surprise for me to get such a big hug from the Israeli radio.”

Raichel and his band have toured the globe, drawing 7,000 (another 3,000 couldn’t get in) to the SummerStage Festival in New York’s Central Park in June 2006 and more than 10,000 to the 70-year-old Stern Grove Festival in San Francisco a week later. Thus far in 2007, the band has performed in Mexico, India, the United Kingdom, Spain, Germany, the Czech Republic and, of course, Israel. Often, the audience gets up and dances at the concerts and long lines form to buy his CDs.

Around a year and a half ago, the band performed in Addis Ababa as part of a roots tour of Ethiopia filmed by Israel’s Channel 2 for a documentary due out this month. The film focuses on Cabra Casay and Avi Vese’s return to their country of birth and to the villages they had left as children.

“It was a very moving journey for everyone,” says the Project’s spokesperson, Shai Shoham.

Coming up in November is an American tour that will include New York, Miami, San Francisco and Los Angeles; a three-week Australian tour in December follows; and one in Europe in February (see www.idanraichel project.com for more information). The band will also perform in celebrations of Israel’s 60th birthday in the United States and Europe in 2008.

The huge commercial success of The Idan Raichel Project stands in sharp contrast to the immense social and economic difficulties—and racism—many Ethiopians face in Israel. The music shines a spotlight on their culture, but many Ethiopian families may not be able to afford Raichel’s CDs—and there is the fact that he is a white man famous for making African music.

Raichel gets visibly annoyed when asked about his perceived interest in Ethiopian Jews. (Nine of eleven songs on the first CD and four of thirteen on the second have Amharic lyrics.)

“I’m not connected with Ethiopians,” he says. “I’m connected with my friends who are Israeli by definition and some of them emigrated from Iraq and some emigrated from Ethiopia. I don’t see them as Ethiopians in the same way they don’t see me as Russian. The Ethiopian element is just one element in our music. People may see it as dominant because it’s the newest, most unfamiliar sound for them.”

All in all, what he is doing is good,” says Shula Mola, chair of the Israel Association for Ethiopian Jews, an advocacy group. “He exposed Amharic music to the general public, and people are happy about that. But there is also anger because he used people’s talents and abilities and authenticity and in the end, it is he who enjoys the fruits.

“Everyone else is anonymous. The amazing success is his, but he could not have done it without all those anonymous people. It’s part of a bigger feeling in the [community] that in every contact—be it with academia, with NGOs—someone benefits, and it’s not the community.”

But not all Israeli Ethiopians agree. “His work is praiseworthy,” says Nigist Mengesha, head of the Ethiopian National Project, a collaboration between the American Jewish community and Israel to advance the Ethiopian population in Israel. “It does me a lot of good when I hear his music on every regular radio station.”

Casay, 24, well known in her own right, has been singing with Raichel for four years. She sees her participation in The Idan Raichel Project as an honor and believes the music has benefited the community.

“It arouses people’s curiosity about our community,” she says. “If there is an Ethiopian kid in class, [his classmates] will ask him, ‘What are they saying in that song?’ Music can connect populations that cannot be connected in other ways.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply