Issue Archive

The Arts: Defiance and Dignity

Contrary to popular belief, Holocaust victims were far from passive in the face of Nazi abuse, and a new exhibit details how and where they fought back.

Between 1941 and 1943, Tema Schneiderman carried out 20 clandestine missions for the Zionist youth movement Dror (Freedom), shuttling between Vilna, Bialystok and Warsaw with news of mass executions and ammunition for revolt. a In a letter, Tzippora Birman, a member of Dror in the Bialystok Ghetto, wrote about Schneiderman and another courier: “They looked like two charming shikses. Their faces radiated cheerfulness as they brought us new hope, news and regards from other parts of the Movement…. They inspired all of us….”

On January 17, 1943, the 26-year-old Schneiderman was caught and deported to Treblinka, where she was murdered.

Schneiderman’s is but one of innumerable stories of courage, resistance and dignity in a profoundly moving new exhibition at New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage– A Living Memorial to the Holocaust (646- 437-4200; www.mjhnyc.org). “Daring to Resist: Jewish Defiance in the Holocaust” shatters the image of Jews as passive victims, highlighting instead a pantheon of heroes. The show also focuses on cultural, spiritual and political activities that, if discovered, often carried the penalty of death. Presented in association with the Ghetto Fighters’ House in Israel, the exhibit will run through July 2008.

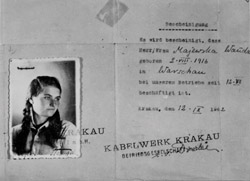

Schneiderman’s forged work document—her alias was Wanda Majewska—is among the 250 artifacts, 150 photographs and images from over 100 individual and institutional donors in 12 countries. Birman’s letter, excerpted in the companion volume to the show, was found in the Bialystok Ghetto archives, which were smuggled out before the ghetto was liquidated in August 1943.

“Jews under German domination are often depicted as… faceless extras in the drama of their own destruction,” writes Israel-based exhibition curator Yitzchak Mais in the companion book. “A more complete perspective will reveal that Jews were…active agents who responded with a wide range of resourceful actions.” The public, adds museum director David Marwell, has confused powerlessness with passivity.

The exhibit opens with an unforgettable image: a hanukkiya in a window, in stark relief against a Nazi flag on a building across the street. Rachel Posner, wife of the last rabbi of prewar Kiel, Germany, took the photograph from their home in 1932. On the back she wrote: “‘Death to Judah,’ the flag says. ‘Judah will live forever,’ the light answers.” The family immigrated to Palestine in 1934.

“We give suggestions in response to the question, What was Jewish resistance?” says museum senior historian Igor Kotler, “but the answer is up to the visitor.” There are the obvious symbols of defiance, such as the fist about to crush a swastika made of snakes on the cover of the underground Warsaw Ghetto newspaper Yugnt Shtime (The Voice of Youth). Other responses were more nuanced: Wooden candlesticks that Victor Elias made in the Gurs internment camp as an anniversary gift for his wife; or soap and scissors from Auschwitz (cleanliness helped maintain a sense of humanity).

The exhibit paints resistance in broad brushstrokes, equalizing well-known names such as that of Janusz Korczak, who refused to abandon the 200 orphans in his care when they were deported to Treblinka, with those of the nearly forgotten, such as Stanislaw Szmajzner, a rifle-toting teenager who had participated in the Sobibor concentration camp uprising and then became a partisan. Instead of singling out individuals, it provides a choir of voices—a collective testament to the audacious ways in which Jews fought back.

Visitors follow the trail of history through the rise of Nazism, occupation, deportation and mass murder. Because the Jewish perspective is presented here, in contrast to the Nazi view, museumgoers must suspend their historical hindsight, says Mais. “The unprecedented nature of the murderous anti-Jewish policies made it nearly impossible for Jews to understand their impending destruction” and influenced their decisions, he writes.

Initially, Jews attempted to lead normal lives, thinking Nazi persecution a “brutal but temporary” situation, according to Mais. They created an official umbrella group— Reich Representation of German Jews—led by Rabbi Leo Baeck that provided relief, education and emigration assistance. Alternative organizations compensated for the cultural, educational, social and professional activities from which Jews were excluded. Suse Flörsheim’s pink relief card authorized her to receive financial aid, while Herbert Grishman’s Maccabi sash established him as a wrestling champion in 1934.

The clash of identities—Am I German or Jewish?— forced many to confront wrenching dilemmas: To stay or go? Where and how? An open steamer trunk owned by the Heim family, among the 60 percent of German Jews who left, reveals objects both poignant and practical belonging to other émigrés: a talit, travel iron, portable typewriter— even a teddy bear that belonged to a young Hans Joachim Hellman.

When 30,000 men were arrested during Kristallnacht, they were told they would be released if they could prove they were leaving Germany soon—a task left to wives and mothers. Regina Berman arranged a student visa and admission to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for her husband, Walter, allowing him to leave Dachau in 1939. Photos recall the familiar stories of the St. Louis, turned back from Cuba, and the Kindertransports that sent 18,000 Jewish children to Great Britain.

One fascinating, little-known story of early political resistance centers on the Bernheim Petition, which protested the loss of Jewish rights in former areas of Poland annexed by Germany. With the backing of Jewish organizations, Franz Bernheim filed a legal complaint against the German government at the League of Nations in 1933. The league forced the restoration of rights in Upper Silesia until 1937. The Jewish community also mobilized against anti-Semitic propaganda, emphasizing their dedication to their homeland. A poster depicts a Jewish mother mourning the 12,000 Jewish soldiers who fell defending Germany during World War I.

Individually, Jews tried to maintain their observances and took their most precious heirlooms with them when they left. Paul Lenger saved his family Torah from a burning synagogue on Kristallnacht, hid it in a drawer under the couch in his home and shipped it to the United States with his furniture shortly afterward. An inscription accompanying a drawing of a Dresden synagogue from a yearbook urges students to take holiness with them wherever they went.

As Germany occupied various countries between 1939 and 1944, ghettos became a fact of life. Believing they would outlive the persecution, Jews in ghettos re-created organized society. Jewish councils provided housing allocations, food distribution, employment, sanitation, health services, shelters, schools, religious services and opened Jewish camps and courts. From the Vilna Ghetto, hospital charts detail numbers of beds and patients; a library chart counts a circulation of 100,000 books. Though no ghettos were set up in Western Europe, the French social service group Rue Amelot provided 26,000 meals at reduced price, 4,000 free meals and 800 free medical exams in one month.

A stage set from Lodz and Jakob Halpern’s violin from Krakow reflect the cultural activities that helped boost morale and self-expression. From Warsaw, a child’s handwritten schedule of classes includes Hebrew, math, Polish, drawing and singing; a color illustration of a Shabbat table follows Friday. The Warsaw Ghetto even ran a clandestine medical school. “We had schools for children in the [Vilna] Ghetto. We had a choir. We had theater. We had discussions. We wrote poems and songs,” recalls Zenia Malecki in her oral history. “Can you imagine? The mothers were called to special discussions. I’ll never forget what they said: ‘Now we are in a cage, but we have to do everything possible that when the children come out of the cage, they should be able to fly.’”

Because the Nazis his the truth fiercely, neither the world at large nor the Jewish communities under the Nazis knew much about worsening conditions. Underground newspapers prepared on manual typewriters— one machine from Belgium has Hebrew keys— disseminated vital information. Their names alone—The Free Word (Warsaw); Fighting Pioneer (Krakow); Youth Fights (France)—reverberate with the liberation they sought. Two of the few radios that enabled communication are also exhibited.

Couriers like Tema Schneiderman helped break the silence. The majority in Eastern Europe were blond, blueeyed blueeyed women who spoke flawless Polish. They accepted dangerous missions “without a murmur or a moment’s hesitation,” in the words of Emanuel Ringelblum, who assembled the archives of the Warsaw Ghetto that were ironically titled Oyneg Shabbes (Joy of Sabbath). Ringelblum’s journal entries describe ghetto conditions.

Determined not to vanish, Jews throughout Europe created records on paper, cloth, cardboard boxes, burlap bags—even remnants of flour sacks. These testaments were often buried or hidden and retrieved after the war.

Two Jewish photographers, Henryk Ross and Mendel Grosman, documented the visual history of the Lodz Ghetto. Grosman hid his camera in his coat, where he had cut holes in the lining to take images unseen. Ross disguised himself as a cleaner to get into the train station open only to German workers to photograph a transport to Auschwitz. In the Kovno Ghetto, George Kadish photographed the Yiddish words Yidden, nekama! (Jews, revenge!) that a dying neighbor scrawled on the wall in his own blood. When the Nazis photographed the massacre of almost the entire population of Faye Lazebnik’s hometown of Lenin, Poland, they gave Lazebnik the task of developing the film—and she secretly made copies for herself.

Amazingly, religious observance and life-cycle events continued. In the Kovno Ghetto, Rabbi Ephraim Oshry was asked whether blowing a cracked shofar in the absence of any other was permitted. Oshry’s shofar is on display, as is the pillowcase that Rivka Gotz gave as a gift to a Lithuanian woman who agreed to protect Gotz’s newborn son, Ben. Because of the prohibition against childbirth, he was smuggled out of the Shavli Ghetto in a suitcase with holes in it.

Below illustrations of Adam and Eve and Noah’s ark, drawn by a father in Bergen-Belsen to teach his son biblical stories, visitors can read David “Dudi” Bergman’s recollection of the cattle train ride from Auschwitz to Plaszow Concentration Camp in 1944: “We got on the [deportation] train and my father said that today is my bar mitzvah. Risking his life, he had secretly hidden a bottle of wine. He took it out. He passed it around to everyone and everyone had a little sip and a toast. And that’s how I celebrated my bar mitzvah.”

The indomitable spirit of women is an especially electrifying aspect of the exhibit. Women fought alongside men, took religious initiative and secretly defied their tormenters. Golda Finkler’s handwritten siddur and Dina Kraus’s handwritten Haggada were used for hidden services in the barracks.

Jews who were put on cattle cars did not know their destinations; Rachel Boehm meticulously recorded the stops on her transport. As arranged beforehand, she then hid her note between the logs of the train compartment so it could be found when the car returned empty:

I list the stations: Basznice, Wrenczyca (it is 5 A.M.), Tarnowitz (7:30), Gross Dombrowka, Krowlewska- Huta (9:30). We keep singing our songs. Auschwitz, 10:30. It is 12:00. Large barracks. I don’t know the name of the station. Men and women are separated. Children are here, too. Old people, too. NILI [Netzah Yisrael lo yishaker: the Eternal of Israel is not false]. Be strong and brave, Rachel.

Gusta “Justyna” Davidson Draenger recorded her story of the Krakow resistance on scraps of paper, between interrogations in prison. “We want to survive as a generation of avengers…,” she wrote. “Will anyone ever be able to comprehend how this group of idealistic dreamers took up arms, in spite of being deprived of the right to live as human beings and as Jews?”

As Nazi destruction escalated, Jews everywhere confronted “choiceless choices,” writes Mais, “impossible dilemmas and obstacles without being certain the course of action they chose would save their lives. Yet, even in this context, they acted.”

Abba Kovner’s manifesto to revolt in 1942 Vilna sounded the call that “our people should not go helplessly like sheep to the slaughter…. If we die—then we die with honor.”

In 1941, when the Nazis occupied the town of Novogrudok in the Soviet Union and killed all but 1,240 of its residents, Dr. Jacob Kagan planned an uprising. He organized the digging of an 820-foot tunnel, depicted in a diorama. Though many were killed, 233 escaped; more than 100 survived and joined the partisans.

Another diorama re-creates a partisan bunker. Tuvia Bielski’s memoir and artifacts from the camp he and his three brothers set up in the woods near Novogrudok tell a story of intrepid leadership. The Bielski Family Camp—the largest Jewish partisan group in the forests—grew to 1,200 members; all but 50 survived. The brothers emigrated to Israel and later, in 1955, settled in Brooklyn.

In fact, close to 100 ghettos organized armed groups. Three of the six death camps—Treblinka, Sobibor and Auschwitz-Birkenau— carried out revolts. In Auschwitz, Roza Robota, 23, enlisted a group of women who worked in the gunpowder room and munitions factory to smuggle tiny amounts of gunpowder in their clothing and in matchboxes between their breasts. Along with three others, Robota was caught and hanged. She sang “Hatikva” before she was executed.

Saving lives, especially those of children, was also a priority for resistance groups. They hid thousands in Belgium, Holland, Italy, France and Germany, often with the help of non- Jews. A photo of teenagers climbing the Pyrenees captures the efforts of the French Jewish Scouts. Even in Berlin, nearly 1,400 Jews survived in hiding. Gisi Fleischmann, a leader of the Slovak Jewish underground Working Group, used transliterated Hebrew words as codes within her letters, otherwise written in German.

In short films interspersed throughout the exhibit, survivors tell their own stories: Artist Alice Lok Cahana revisits Auschwitz and remembers a secret Shabbat celebration. “We started to sing ‘Shalom aleikhem malakhei ha-shalom,’” she recounts. “And as we sang the melody, other children came around us and they started to sing with us. Somebody was from Poland; somebody was from Germany; somebody was from Hungary…all thrown together…and suddenly the Hebrew songs and prayers, the Shabbat, united us in the latrines of Auschwitz.”

With testimony like that, it is almost impossible to leave the exhibit without a renewed sense of respect, even awe, at the fire that leaps from the stories, artifacts, voices and faces of the survivors and victims, many of whom were, ironically, consumed by a different and dark kind of fire.

As Mais concludes, “The question is not, as some would pose it, Why did Jews fail to mount cohesive and effective resistance to the Nazis? but rather, How was it possible that so many Jews resisted at all?”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply