Issue Archive

E-mail from Virtual Russia: Music Without Borders

Today’s musical transformation in the Former Soviet Union has Jewish roots and it is being led by Russian Jewish artists who once fled the country.

A young street tough swaggers down an alleyway, an accordion slung across his chest. The camera pans back to a parking complex where a group is rapping in Russian about being urban Cossacks from a lousy neighborhood. A heavy-set, bearded gentleman enters the scene. His gravelly yet melodic voice interposes itself between rap lyrics with a simple folk arrangement about male camaraderie on the steppes.

The two styles clash in a duel of tunes and genres to create a harmony of contrast in this music video.

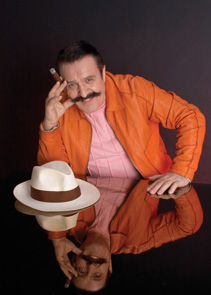

The video, Women Are the Last Thing, and the song of the same name are the work of Russian hip-hop artist Sheff and Russia’s current “King of Shanson,” Mikhail Shufutinsky. Though a tongue-in-cheek lark about male bonding, it also illustrates the dynamic music scene in the Former Soviet Union, which merges the new and foreign with the classic and local. Ironically, Sheff is the local and Shufutinsky is an American. A Jewish former Muscovite, Shufutinsky and his Russian folk music have gone from near oblivion to the top of Moscow’s charts through the detour of American immigration.

Shufutinsky’s journey is echoed in the experiences of a number of Russian Jewish musicians who fled the FSU. And as artists such as Shufutinsky, Isaak Loberan and others return, they are helping transform the music of the culture they once abandoned.

Loberan, who grew up in Moldova and today makes his home in Austria, is bringing klezmer back to East European regions that in the early 20th century comprised the Pale of Settlement. He dedicated himself to Jewish music in 1996 after a trip to Krakow. “Seeing the destruction of Jewish society—there had been 80,000 people there [before the Holocaust], now there are 200 and most are from elsewhere—I had a need to keep Yiddish songs alive,” he says. He and the Ensemble Scholem Alejchem, the folk band he founded, draw a mostly non-Jewish audience to their klezmer and Yiddish music concerts. The locals seem to realize that something inherent is gone and needs to be recaptured, Loberan adds.

The troupe also tours throughout Europe and the West and has put out a number of CD’s; one of his most ambitious is an overview of Jewish diaspora music, From Spain to Chernovitz, which includes haunting Ladino love songs as well as klezmer.

“Often we will do a free concert, perhaps at a festival,” says Loberan of his experience in Ukraine, Moldova and the Czech Republic, “and the next [year] we will draw a sell-out crowd.” But that was only the start. “I realized that most everything we did was from American Yiddish recordings made between 1907 and 1940,” he explains.

With a grant from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Austria in 1998, Loberan undertook a four-year project to collect and study Jewish music from the Pale of Settlement. He found it had been preserved in non-Jewish folk music; for example, the melody “Mitzva Gedola” was adopted unchanged into Moldavian dances, and 19th-century notes on “Hatikva” show a Moldavian folk tune was based on the Hebrew song. Loberan has teased these layers apart and now brings the re-created music to appreciative audiences.

Klezmer may be the more well-known genre in the United States, but in Russia it is shanson—the name, not the style, is adopted from the French chanson—that is bringing Jewish sounds to popular music. Developed in the intimate atmosphere of smoky bars and private parties, shanson encompasses a variety of folk music including blatnoi (criminal ballads); bardic (sentimental songs about politics and social issues); and a light-hearted song just called shanson. Vladimir Vysotsky—who died in 1980 and whose father was Jewish—remains the country’s most famous singer and master of the genre.

According to Loberan, the klezmer-shanson interplay began when klezmer musicians in the 19th century came to the thriving port city of Odessa and created an urban music for the new breed of city Jews. Some of those klezmer-blatnoi hybrids are performed today virtually as they were in the past—for example, the Yiddish satire “Mein Yihus” (“my elder bother is a card shark, my mother is a prostitute”).

Shanson was largely underground through the end of Soviet rule. Today, however, Alexander Rozenbaum, a deputy in the Duma, is a Jewish shanson singer-songwriter who writes Jewish-themed songs. He has characterized his music as “amateur night from Sing-Sing.”

Shufutinsky and another émigré musician, Villi Tokarev, have brought shanson to the forefront of the Russian music scene, both in America and the FSU. The popular Shufutinsky does not shy away from Jewish-themed melodies, among them Rozenbaum’s soulful “Song of the Jewish Tailor,” blatnoi ballads filled with names like Benny and Moishe, and songs of Odessa.

When asked if he had lived in Odessa, he often quips, “I have to say: Not all of us can be so lucky.” A typical song is “The Romance of Izya Schneerson,” about the illegitimate son of Uncle Monya the tailor. Schneerson was “as beautiful as Yehoshua Navi” and “at cards wiser than Solomon” but lost his girlfriend in a card game and committed suicide.

The up-tempo clarinet, horns and accordion, and tragicomic sensibility of the stories, all illustrate the connection between the klezmer tunes collected by Loberan and the vast swath of shanson, whether obviously Jewish or not, performed by Shufutinsky.

Tokarev’s music has a more modern feel. With strong, biting humor, he has moved Jewish blatnoi from Odessa to New York, with ballads of pickpockets and tax cheats. The composer-singer himself is an oddity: He is a Kuban Cossack (of the same tribe that was the terror of 19th-century Russian Jew). Classically trained in a Soviet music academy, he immigrated to the United States in the mid-1970’s. He built his career in the Brooklyn nightclubs of Brighton Beach, and his songs betray an intimate knowledge of and affection for his audience: “Why Are the Jews Leaving?” is a soulful examination of the dynamic of immigration; “Happy New Year, Aunt Chaya” is a rude ditty about shady business in Brighton Beach. In 2006, he toured to promote Hello Israel, his second Jewish-themed collection, performing at the Moscow Jewish Community Center and sold-out concerts in Israel.

Loberan and Shufutinsky also had classic Soviet music training. Loberan played for the Moldavian Opera Theater. Shufutinsky was more of a rebel. “I fell asleep and woke to the Voice of America,” he says, and he participated in illicit jazz jams.

It was a desire for a better life and greater creative freedom that motivated the musicians to leave their countries and careers. “There was no overt anti-Semitism,” recalls Shufutinsky, who left the FSU in 1981, “but…they would not allow me on foreign tours….” For Loberan, however, it was the fear of post-Soviet turmoil that caused him to flee. While on a train returning from a European tour in 1991, he heard the radio announce a coup at home and decided to get off at the Austrian border “with nothing but a small valise and the bow of my contrabass,” he says. “It would take a year of adventures before I got the contrabass back.”

Shufutinsky, originally an instrumentalist, took the immigrant scene by storm as a vocalist on his first album with renditions of the works of the already immortal Vysotsky and the then unknown Rozenbaum. Soon, the songs he performed in the Little Russias of New York and Los Angeles made their way back to the FSU. In 1990, he accepted an invitation to visit Russia and sang at 75 packed stadium concerts. He now spends most of his time in Moscow, while regularly performing in Israel and America, where he has a home in San Diego.

Loberan’s path was less gradual. “I gave 22 years to classical music and wanted to focus on Jewish music,” he recalls deciding after his eye-opening trip to Krakow. He wrote a book on his research, Klezmermusik From Moldavia and the Ukraine (published in German, Russian and English by Varwe Musica Publication, Austria), and the Austrian ministry is producing his new Jewish music CD.

There is a second, younger generation of Jewish Russian returnees whose music is influenced by American rock rather than Russian folk. Among these groups, which includes the rock band B-2, are the Sisters Rose—Dina and Ella—twins who left the FSU as children. The duo performs pop, Russian and Jewish favorites, including an 1980’s-inspired English remix of “Hava Nagila” called “Let’s Dance,” which intersperses the familiar hora tune with a dance beat and lyrics that encourage listeners to “Come on and join the fun….” Though today they perform mostly in Russia, on rare occasions they appear in Brighton Beach nightclubs. Ironically, their repertoire includes that streetwise ode to their Odessa forbears—“Mein Yihus.”

Where to Find Shanson

- RBC: 718-769-8605; www.bukinist.com (a mostly Russian site)

- Isaak Loberan’s book and CD’s are available from the Center for Jewish History book store in New York: 917-606-8220.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply