Issue Archive

Feature: Home, In So Many Words

When our parents are alive, they keep hold of the past. After they die, we have to find a way to do it ourselves. One woman set out to save mame-loshn, “the linguistic homeland of a people without a home,” and find her own way home.

A soft rain was falling as a white-haired woman slowly made her way to the microphone in the courtyard of Vilnius University. “Tayere talmidim!” she began. “Dear students!” I leaned forward to catch her words through the pattering of drops on my umbrella. The old woman was a member of the tiny, aging Jewish community in the capital of Lithuania. Her name was Blume. “How fortunate I am,” she said in a quavering voice, “that I have lived long enough to see people coming to Vilnius to study Yiddish.”

Seventy-five of us huddled together on wooden benches under the heavy Baltic sky. We had come from all over the globe to spend a month at the Vilnius Yiddish Institute. Some were college students looking for credits; others, middle-aged like me, had arrived in the former Jerusalem of the North in search of something else.

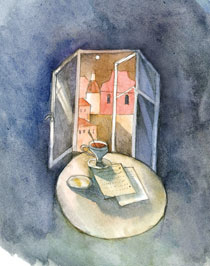

Years earlier, when my mother died, I’d developed a yearning for the language of my ancestors—the Jewish ones, that is (my gentile father’s family hails from Germany and Great Britain). My mother had used the old Jewish vernacular only sparingly, like a spice, but when she died I found myself missing the hints of the Old World that I used to hear in her pungent Yiddish expressions. At the window on a rainy day: “A pliukhe” (a downpour). In the kitchen: “Hand me that shisl” (hand me that bowl). On the telephone: “The woman’s a makhsheyfe” (the woman’s a witch).

When my mother was alive, I could count on her to keep hold of the past. Now that she was dead, not only had I lost her, but all those who had gone before seemed to be slipping out of reach, too. I hadn’t been able to save my mother from cancer, but maybe I could help save mame-loshn. Maybe Yiddish, which has been called “the linguistic homeland of a people without a home,” could offer me the comforting sense of continuity that had been ruptured by my mother’s death. In helping to keep that cultural homeland alive, perhaps I could find a way home myself.

I started with an elementary Yiddish phrase book, then tried an evening class at a nearby Jewish college. The Germanic sounds felt comfortable in my ears and mouth, and the Hebrew alphabet was daunting but not impossible. I listened to tapes, copied out grammar exercises and thumbed my dictionary till the binding broke. Bit by bit, I began to feel a connection to the language once common in lanes, meeting halls and market squares on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Now in Vilnius, or Vilna, the former capital of the Yiddish world, I hoped to deepen that connection. In my childhood, Lithuania had always seemed utterly inaccessible, as if it existed in another dimension, like Atlantis or Narnia. No one from my family who had made it across the Atlantic had ever been back there. Yet here I was, looking up into the same sky that had sheltered my great-grandmother Asne and her dairy farm and my great-grandfather Dovid and his study house. Under this sky, my grandfather Yankl had been a yeshive bokher and then a socialist before running to America to escape the draft. Here, during the Nazi era, my Uncle Velvl had been confined behind barbed wire in the Shavl ghetto. And here, after returning from Dachau, my Uncle Aron had been arrested and exiled to Siberia. As the rain continued to fall and the damp courtyard darkened, I shivered. It was a hard place, this land of my forebears—a country where Jews and their culture had been systematically exterminated—a curious place to come looking for a sense of belonging.

The next morning I hurried through the courtyard and up a steep stairway into a classroom that was crammed with four rows of battered wooden desks. The Yiddish instructor, a bearded scholar, did not actually carry a stick like a melamed—a teacher in the one-room Jewish schoolhouse of old—but his rules were strict. “Study the assigned texts with care,” he said. “Questions will be allowed only about words that do not appear in your dictionaries”—and having written one of the dictionaries himself, he knew exactly what was in them. “Not a word of English will be permitted,” he added.

As we took turns reading aloud, I kept a finger glued to the page. If my concentration faltered for a second, I was lost.

When the teacher spoke, whole paragraphs went by in a blur. For some reason, my hand kept flying into the air with questions and comments. The moment I opened my mouth, however, I realized I had no idea how to get to the end of a sentence. In this language that was not really my own, it was as if I were two people. One was an impractical idealist who set off with supreme confidence into the unknown, while the other was a benighted worker who ran ahead, frantically trying to build a road for the journey.

Outside the classroom, amid the pastel façades and crisp spires of 21st-century Vilnius, traces of the old Jewish world were few and far between. But the last Yiddish speakers of Vilnius led us on long walks that began on cobblestoned Zydu Gatve (Jewish Street). Blume returned with Fania and Rokhl—stumpy, tireless women. “Here,” said Fania after leading us into a vacant lot, “once stood the Great Synagogue, and there was the famous Strashun Library.” Back when she was young, she said, “schools and theaters used to crowd the narrow lanes and the streets resounded with Yiddish,” as learned rabbis brushed up against fish peddlers, and young people like my grandfather engaged in fierce debates over politics and religion. Then came the Nazi invasion and the ghetto. Some 70,000 Jews were jammed into the old Jewish quarter on this very spot where we were standing amid trash bins and dusty playground swings.

“One night,” Rokhl said, “I was awakened by the barking of dogs. Outside my window, the police were driving long columns of Jews. The people had their children by the hand and their belongings tied up in bed sheets, white sheets in the black night.”

More than 90 percent of Lithuania’s 240,000 Jews died during World War II. Some of our elderly guides had fled to safety before the massacre began; others, like Rokhl, had escaped from the ghetto and joined the Red Army in the forests. Now, sometimes weeping, sometimes radiant, they talked and talked—about the world that used to be, about the people who were no more, about their own miraculous survival.

The flat where I lived with my roommate, a retired teacher from California, was located within the former ghetto. In the evenings, we used an old-fashioned key to open the creaking wooden door into our courtyard and then climbed the stairs to our rooms. Bent over our books at the kitchen table, we did massive amounts of homework, whispering under our breath as we riffled through our dictionaries. Oy, those verbs, with the umge-this and the oysge-that, the aroysge-this and the farge-that! Every paragraph was an ordeal. On top of each sentence I penciled a spidery layer of interpretation, dividing the verbs and the compound nouns into their component parts, underlining words I didn’t know, numbering and rearranging the elements of especially convoluted expressions. As I grew tired, the letters swam before my eyes until the page of sinuous Hebrew characters resembled a sheet of matzo. At times I was near tears. Why couldn’t I understand? Why wouldn’t this comfortable mame-loshn reach out to embrace me?

In the mornings, I began to awaken with Yiddish words on my tongue, which I would savor with a slice of dense black bread topped with butter and cheese from Rokiskis—the very town where my great-grandmother had operated her dairy—and little knobby cucumbers. One week the market offered tiny apricots and the next, small purple plums. Here in the Old World, there was no abundance. Only the shabes tish—our weekly Friday night celebration at the Jewish community center—was lavish. The long tables spread with snowy cloths were loaded with candles and wine and platters of fruit and nuts, cheese and kasha and challa that tasted just right. Late into the night, we sang endless nigunim, wordless melodies full of joy and sorrow.

Day after day, our teachers guided us into the most intimate linguistic nooks and crannies. One morning we pondered the mysteries of verb aspects: the differences among “I kiss,” “I am kissing” and “I keep on kissing.” Another time we ran our tongues over long strings of adjectives formed from nouns: oaken door, woolen glove, golden ring, clay pot. On yet another day, our instructor informed us that “krenken is to get sick, but krenklen is to fall ill again and again in a less life-threatening way.” Later on, we were tickled by the playful variety of Yiddish diminutives: Blume, Blumele, Blumke, Blumkele.

More and more, I found words emerging suddenly from the mist, or whole sentences popping out of my mouth fully formed. At the end of every session, we sat back and listened as the instructor read from his favorite texts in a sonorous and elegiac voice. It’s a mekhaye—a great pleasure.

In the evenings, as I worked my way through my assignments, vivid scenes began to come into view. One story I read took place at the turn of the 20th century in the courtyard of the Great Synagogue—the very courtyard where Blume, Fania and Rokhl had told their tales. On the first page, thousands of Jews were gathered for the funeral of a famous Talmudist. Slowly, in an upper story high above the crowd, a window began to open, and as a curious boy leaned out to survey the scene, I leaned out with him.

Another text brought me to a dark corner of the Vilna Ghetto during World War II, where a writer sat scribbling, imagining himself to be a bell with somber tones that shattered the silence of the black ghetto night. How privileged I felt to be able to catch the tolling of that bell.

Halfway through the month, along with these literary characters, I began to sense another set of characters beside me as well: my mother with her love of a tasty turn of phrase; my grandfather with his devotion to Mark Twain and other giants of American literature; my great-grandfather Dovid, whose beard had quivered over the folios of the Talmud; and, finally, perhaps not a reader at all, my great-grandmother Asne, the dairywoman and mother of nine, who must have been possessed of a fearsome persistence. Even more than I had hoped, learning Yiddish had linked me to my ancestors and brought the past to life.

On weekends, I visited the grim headquarters of the Soviet secret police, now a museum, where Uncle Aron was imprisoned before being sent to the gulag, and the tumbledown alleys of the old Shavl ghetto, where Uncle Velvl had been confined. I traveled to the tiny hamlet where my grandfather grew up—not even a crossroads, really, just a stand of trees and a scattering of houses and barns and marigolds nodding in the sun.

In the town of Rokiskis, I walked down Synagogo Gatve, where three wooden study houses used to stand—the green one, the red one and my great-grandfather’s yellow one. On the outskirts of town, I stood in the green glade where the Jews of Rokiskis had been lined up and shot. As the wind stirred the leaves of the birch trees overhead, I listened, and in my head I answered: Ikh bin do, I am here.

Back in Vilnius, at the urging of my Rokiskis guide, I paid a call on Ida, an 83-year-old woman with strong features and penetrating eyes, who had grown up not far from the three colorful study houses. “Kumt arayn (come in),” she said, as she ushered me into her parlor, where a table was set with cream cakes dotted with red currants and cherries in a silver bowl. A visit from a Rokiskis landsman was clearly a special occasion.

Ida was one of only two in her entire family to survive the war, she told me in Yiddish as we sipped tea from delicate china cups. “Every September,” she said, “I travel to the forest near Rokiskis”—the same place I had just been—“to honor the memory of my loved ones.”

There was something she wanted from me, something I couldn’t figure out. Again she explained, and again I strained to understand. After a while her meaning became clear. She wanted to know if she had been visiting the right place all these years. Were the bones of her mother and father, her brothers and her aunts and uncles and cousins and grandparents, truly buried beneath the grassy tufts of this particular clearing? Or were they in fact lying in another killing field, in Obeliai, a few miles up the road? “Is there a list somewhere?” she asked.

I shook my head. “Neyn,” I said, I didn’t believe there was such a list. And no, I couldn’t answer her question. But what I could do, as her attempt to tend to the dead touched my heart, was hold her hand. I could hear her words, and respond, however haltingly, in soft syllables of mame-loshn.

As our month drew to a close, my roommate began to relax over her books at the kitchen table. She dreamed of her swing under the orange tree back in Los Angeles.

I kept going full steam, still wrestling with every line of every assigned text, still looking up every unfamiliar word in the dictionary, then walking for hours through the city, taking in the pink walls that glimmered in the last light, the squares where young people—the inheritors of this land with its huge and complicated history—sat in the outdoor cafés under the stars.

On the last day of class, we finished a story written after the Holocaust in which the narrator finds himself pulling a wagon piled high with dead bodies. So it is for all of us, I thought, as we go forward lugging our past behind us. It was our hardest story yet, a thicket of obscure words and fiendishly complex constructions, but I didn’t mind. I had come to feel that in Yiddishland, this place of love and of pain, it was the effort itself that mattered. Simply trying—to listen, to understand, to speak—brought a deep satisfaction and the sense of connection I had been seeking.

At the graduation ceremony, the sun shone in a blue sky, and there were flowers and herring and vodka. Alas, Blume was too ill to attend, but Fania and Rokhl were there to send us on our way. “Zayt gezunt,” they said—goodbye, be well. We gave a kiss, we kissed, we kept on kissing and crying. It was hard to leave.

Ellen Cassedy, a journalist living near Washington, D.C., is working on a book about her journey to Lithuania where, in addition to studying Yiddish, she explored how Lithuanians are engaging with the treasures and the tragedy of the Jewish past.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply