Issue Archive

Family Matters: Room on the Farm

During world war II, Catholic Charities USA brought young Polish Catholic women to America for refuge. They placed them with Catholic families, and the young women usually became maids or nannies.

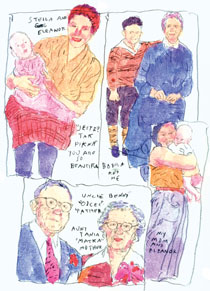

Sixteen-year-old Stella was obviously pregnant when she arrived. Her parents were dead, and she was unmarried. She cut an imposing figure, the sort of girl boys notice immediately.

Stella was supposed to have been placed with the Britchkas, who lived behind their family-owned gas station. But the Britchkas would have nothing to do with her. Catholic Charities tried other Polish Catholic families, but none would accept her.

Stella was taken to live in a cramped room in the basement of St. Hedwig Catholic Church, where she was berated and mistreated by the nuns who told her she was lost to God forever. Once, she ran away in the middle of the night and the police found her sleeping between empty milk crates behind a nearby dairy. She was frightened and confused, and when they sent her back to St. Hedwig, she screamed and cringed after the nuns took her hand. The director of Catholic Charities was completely frustrated and bewildered as to what to do with Stella, other then put her on a ship back to Poland.

At a meeting with other religious leaders in the local YMCA, the director sat next to Rabbi Eisenberg and mentioned Stella to Rabbi Eisenberg and the absolute bind Catholic Charities found themselves in. Rabbi Eisenberg said, “Let me think about it.” That afternoon, the rabbi got into his ’38 Plymouth and drove to Uncle Benny’s farm. Uncle Benny, who was active in the shul and a great friend of the rabbi, met him in the driveway.

Uncle Benny was funny, unsparing, sharp and fundamentally good spirited. Aunt Tania made strawberry jam tea and cut up her raisin cake and, along with my bobba, they all sat at the kitchen table under a fake Tiffany lamp, and the rabbi spoke of the difficulties engulfing Stella. “Would it be possible for her to come to the farm for a short while until accommodations could be made for her?” he asked.

For a moment no one said anything. “Rabbi, we have no children, what do we know about babies?” Uncle Benny asked. “What would we do with her? What do we know about Catholic girls? What do we know about a girl with a baby?”

Aunt Tania said, “Don’t be foolish, Ben. Frances has two children, Harry has three children, and Sarah has two girls. It will be fine.”

My 80-year-old bobba sat straight up in her chair and said in Yiddish, “Bring the child here. She’ll go back to Poland over my dead body.”

Aunt Reba had died a few years earlier, and they spruced up her room for Stella. Uncle Benny went out with a shopping list filled with suggestions from everybody in the family and bought a crib, a bassinet, a rocking chair, a baby carriage and balls and jacks and jump ropes. My bobba made the baby new clothes as she had done for me when I was born. Aunt Tania made new curtains, and they bought a new mattress for the bed.

Stella blossomed and found family, home and safety on the farm.

Benny and tania and bobba spoke to Stella in a patois of Russian and Polish, which was close enough to make sense to all of them.

Stella became an integral part of the family, and when Eleanor was born a few months later, it was an astonishing event in the lives of three elderly Jews and a Polish teenager. When Stella’s water broke, Uncle Benny rushed her to the hospital with my bobba comforting and reassuring the very frightened girl in the back seat. “Babcia, Babcia,” she said. My bobba was holding her very close and said in Yiddish, “Shah, shah, kleine.” (Sh, sh, little one.) After Stella gave birth and held the baby, she cried along with Uncle Benny and Aunt Tania and bobba. “Jeste? Tak pikna,” Stella said. “You are so beautiful.”

At the hospital, we all showed up, aunts and uncles and cousins. Stella had a family. When the attending nurse asked for the next of kin, Uncle Benny said, “Benjamin H. Bloom.”

When they brought Stella home, there was a party and the aunts and uncles and cousins and the neighbors came. Mr. Gold played “Shein vi di Levone” on his violin. The director from Catholic Charities came with the rabbi and his wife. My cousin Ruthy hung up streamers. Stella called Uncle Benny “ojciec,” father, and Aunt Tania “matka,” mother.

Eleanor was my baby sister. I pulled her in a red wagon, and we picked Uncle Benny’s strawberries together and Aunt Tania made jam. We sat on the bank at the front of the lawn and waved to the cars and trolleys passing by. We watched the dragonflies and grasshoppers and caught lightning bugs and built cities out of grass clippings.

When Eleanor was 4 or 5, Stella met a young man, Paul, at church and fell in love. The church would not marry them so Rabbi Eisenberg made some adjustments and performed the ceremony under a sickle pear tree in the backyard. The aunts and uncles and cousins were all there. Uncle Benny gave Stella away and my bobba cried under the makeshift chuppa, the pear tree.

Paul smashed a glass, and all the cousins and aunts and uncles shouted mazel tov. Mr. Gold played “Shein vi di Levone” again on his violin, and the rabbi danced with bobba, and the director of Catholic Charities danced with Stella, and everybody drank schnapps and ate and it was a sweet wonderful day. Truly a simcha.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply