Issue Archive

2006 Harold U. Ribalow Prize: The Genizah at the House of Shepher

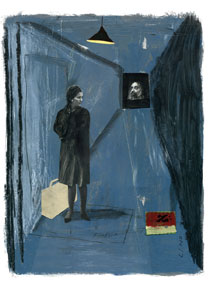

Shulamit, a biblical scholar from England—and the central figure in Tamar Yellin’s novel The Genizah at the House of Shepher—returns to her grandparents’ home in Jerusalem after an absence of many years. While visiting aunts and uncles she becomes embroiled in a family feud over possession of the “Shepher Codex,” a mysterious manuscript discovered in the attic of the family home. In researching the origins of the Codex she uncovers her family’s history, which includes a mission her great-grandfather undertook to discover the lost tribes, and she befriends a stranger in a caftan who has an intense interest in the manuscript. This lyrical excerpt, describing Shulamit’s arrival in the Holy City, provides a taste of why Yellin’s book won her the 2006 Harold U. Ribalow Prize.

I came to Jerusalem at night, in darkness, after a long absence, rain streaking the windows of the taxi as we rode from the plain to the hills. Outside, at first, there were bright signs, a golden egg, a drive-thru takeaway, a giant smile surrounded by flashing lights. We might have been in America. We might have been anywhere. Then we were on the highway. We were nowhere. Darkness, hunched trees. A change in the air. A whiff of petrol and bitumen, a hint of the sea or the desert. Strangeness. Rain.

Then as we began to climb I closed my eyes and thought I recognised the old route, its rises and turns inscribed on my memory. But the road had changed. It had flattened, uncoiled and stretched itself into something unfamiliar. And when I opened my eyes, instead of the darkness of the hills there were masses of lights, strings and clusters of lights as far as the eye could see.

“What’s that?” I asked.

The driver answered: “That’s Jerusalem.”

The engine strained and the windscreen was flooded with rain. And then we were on the road I recognised: a steep curve, a petrol station, ruins, and, hanging from the edge of the deep valley, a shanty which had clung there, perhaps, for more than a hundred years and still not fallen off. Of all the cities of the world Jerusalem has one of the shabbiest gates of arrival, and coming or going one is greeted by graves.

My driver had the address: Kiriat Shoshan; and sliding from lane to lane he rushed the lights, pulled up at the next red, crackled his radio. Did I know this stretch? I was already lost again, in a labyrinth of traffic and asphalt and hotels and shopping malls, at sea in a changed city. Yet this road I did remember, as we turned into a quiet boulevard lined with apartment blocks, a long straight road with a regiment of trees, opening at its far end into a small square containing a children’s playground, a sandbox and a synagogue. And there on the corner of the square was the house itself, older than ever, more worn and weather-beaten, with one of its shutters hanging half off and, darker and denser than I recalled, the line of five cypresses my father planted.

Thin clouds blew over; a toenail of moon hung in a ragged sky. I stood with my suitcase on a well-known patch of ground, as if on a small disc in the middle of a strange universe.

And sitting in the window was my Uncle Saul, just as I had imagined him, hunched at the kitchen table in my grandfather’s caftan, huddled over the paraffin heater, listening to the radio. He rose to his feet and peered at me through his round glasses.

“Hello Saul,” I said. “It’s me, Shulamit.”

Twenty years had not made much difference to him. He was old before and he was older now. His hair was silver then and it was silver still. He walked as he always had, with a shuffling stoop, hampered now by the folds of my grandfather’s caftan, which hung on him limply, tattered by moth and wear, and gave off a morbid, rotten odour. God knows where he had dug it up. From the bottom drawer of the pot-bellied walnut dresser, maybe, or the camphor-smelling wardrobe in the back bedroom. He wore it, I suppose, because it was warm, and possibly also for another reason: imagining, perhaps, that by some act of transubstantiation he had become my grandfather.

He was as I remembered him, a man of few phrases and a few very pungent gestures, able to express with one eyebrow the whole significance of twenty years’ silence and absence punctuated only by a cheap New Year card. “Shulamit,” he said. And he welcomed me into the house with a reverent motion, like the curator of a museum which was soon to close.

I dropped my bag and stepped forward, to take in the full squalor of that house which had once been the living heart of the family and was now a slum. Furniture stood piled in obscure corners. There were towers of boxes and stacks of bed linen, fragile pyramids of kitchenware; domestic rubble swept into untidy heaps. Torn strings of tatting decorated the windows. The walls were bare, but a dusty mobile of blue-green Hebron glass still hung from the doorframe where I remembered it.

I turned to my uncle, who gazed across the sea of memory with the same inward stare, magnified by the lenses of his ancient spectacles; and who looked up at me now as though I were nothing more than a ghost, come back to haunt his already haunted solitude. I managed a smile.

“I’ve come for a visit,” I said.

Someone appeared to have been mixing concrete in the bath. In the middle of the bathroom floor a zinc bucket stood like an abandoned child: It seemed to contain underpants, and a scientific bloom of grey-blue water mould.

I splashed myself quickly under the rusted cold water tap—armpits, face and neck—and dried myself with a towel which smelt all too sweetly of home. Emerging, I bumped clumsily into Saul.

“Oh—Ouf—!”

This was our morning’s greeting.

In the semi-abandoned kitchen an ancient kettle stood on the primus stove and a disembowelled loaf of bread lay on the table in a pool of crumbs, where my uncle, listening to his radio, had sat pulling fistfuls of it for his supper without bothering to wield a knife. Among the crumbs lay a number of dead matches he had used to light the fire and, later, to pick his ears.

The refrigerator was empty and streaked with yellow dirt.

Thirty years ago this had been the living heart of the house: a pulsing centre of nourishment and talk, boiling, beating, baking and conversation. Here my aunt, Batsheva, had walked back and forth, pounding matzo meal in a brass mortar; here at the kitchen table my grandmother had rolled and cut noodles for the Sabbath soup. Here we hungry children had come to raid the fridge, whose shelves had groaned under the weight of apples and grapes, plums and peaches from the Machane Yehuda market, blocks of white salt cheese, trays of honey cake and halva and stuffed monkey.

Now it had reverted to a primitive state: cramped, minimalist, resembling an army mess with its rusted taps and primus stove. The brown tile, added sometime in the fifties, and the rough-and-ready units knocked up by an enthusiastic cousin, were coming away from the walls; behind them lay bare stone, cobwebs—the lurking evidence of a more basic past.

But the house had always been primitive, cavelike, wearing its stones naturally, its walls bare; it had always had the air of a temporary dwelling. Even as children we had known its days were numbered, that every visit we made drew on a finite store: like an old and sick relative one visits and takes leave of, never knowing if this time might be the last.

“And where is your brother, Reuben?” Saul had demanded last night, as though he expected us to arrive in tandem as we always did, one trailing at the other’s heels, the long and the short of it, the redhead and the dark, even though we had been young adults when he last saw us: still children after twenty years.

“Mike, now,” I had corrected him. “He calls himself Mike.”

I could not tell him that Reuben was not interested, that Reuben had tried to forget; that Reuben did not want to come.

It was Uncle Cobby’s letter which had brought me here; a fragile scrawl in trembling schoolboy script which was an event in itself, for only a landmark moment in the family history could have inspired him sufficiently to write to me. Aunt Batsheva was dead; the house had reverted to its proper owners; time had run out for its hallowed walls. By summer it would be gone: a five-storey apartment block would take its place. If I wanted to see it again I must come immediately.

I could hardly say, even now, what maelstrom of feelings rushed in and took hold of me: what vortex of nostalgia, grief, regret I was suddenly sucked into when I read his letter. For years now I had existed in a state of numbness, the kind of deep calm which succeeds a violent storm. I hadn’t believed myself capable of strong feeling any more. I lived an orderly life; I lived alone; the past and my heart were buried and forgotten. And now this sudden resurgence, this impulsive rush into everything I had escaped from, subdued and shrouded in forgetfulness.

I called up my brother and asked if he wanted to come.

“You must be joking!” he snapped. “Why the hell would I ever want to go back there?” And he added: “You shouldn’t go either. You’ll only upset yourself.”

But I wanted to go; I wanted to be upset. I wanted to feel something after all this barrenness. So at the first opportunity I booked my lone ticket and packed my single bag. I returned on the wings of eagles in a jumbo jet, and rising high above the busy glittering world, I looked down on the tiny distant pinprick which was my former life.

I pushed open the stiff back door with its nine panes of variegated glass and stepped outside. The morning was warm and soft; no longer damp, but with a blue sky of indefinite depth and a whiff of spring in the air, though at this time of year the squally latter rains could fall at any moment. The square was as it had always been, bordered with pepper trees and ringed by apartment blocks: greyer now, and scarred with leprous patches, but hidden in rising skirts of cypress and oleander. The house had changed however: its shutters broken, its garden awash with litter, decorated with a smashed perambulator which sat atop the rubbish like a strange cherry on a very ugly cake. The wall at the corner of the plot had fallen, and the cactus plants stood shrivelled, half-dead, their black limbs strewn like snakes across the broken path.

I rounded the path and climbed the few steps to the verandah, where in a tide of dead leaves two broken chairs sat turned towards each other, like a long-abandoned conversation. The square was quiet: A young mother wheeled a stroller past the synagogue and a religious Jew in caftan and sidelocks lingered opposite, under a pepper tree.

I remembered how once the house had been filled with people, how I, a visiting child, pale and alien in my English skin, had touched the spines of the unfamiliar plants and felt a fear of scorpions. Or sitting in the shade of the cypresses, how I had watched the patient ants, hour after hour, pursuing their labouring trails in an ecstasy of idleness. The house was empty now but here I was again, still English and pale, still afraid of scorpions, despite the fact that in all those years I had never laid eyes on a single one; though one evening, returning from an excursion, I had seen my father, with a practised hand, remove a black snake from the heart of the oleander.

But that sort of thing was to be expected: my father retreating to his earliest self, instinctive and at ease, like a captured animal released into the wild; climbing trees to collect carob pods, brushing a three-inch cockroach indifferently from his shoulder. He was a native restored to the tribe, comfortable as we had never known him; while we the outsiders, Reuben, my mother and I, struggled with sunburn and mosquito bites, strange customs, stomach upsets and a foreign language. Summer after summer my mother would spend her days lying in the darkened guest room lined with family photographs, a cologne-soaked handkerchief covering her eyes; fearing perhaps not scorpions but something more feral and terrifying: my father’s absence, her own abandonment.

“You won’t recognise the Plotsky house.”

I started. Saul’s face had popped up at the French windows like a pale marionette’s. The next moment the window itself sprang open. The wood had swollen, and the frame scraped across the tiled floor with a wrenching splitting sound.

“The Plotsky house is gone. And the Plotsky garden. All apartment blocks. They sold it for three million.”

“And Avram?”

“Avram went to America. Avinoam Plotsky killed himself.” Saul shuffled across the verandah, his slippers nosing their way through leaves and dust, his eyes blinking like some burrowing creature’s unaccustomed to the sunlight. “Terrible to kill yourself with three million.” He peered across the square as though looking for something.

“Terrible to kill yourself in any case,” I said.

I was flooded by sudden guilt: guilt at the years of painful procrastination, guilt at having stayed away too long. As if by returning more often I could have slowed the pace of change, arrested progress; saved poor Plotsky even, in whose tropical garden I had played games of jungle exploration as a nine-year-old. All those years in which I had kept away I had never once thought of him, and now he was dead.

Now Saul began absentmindedly to explore his right ear with his little finger, waggling it back and forth, examining the excavated contents, meanwhile staring out across the square. His gaze seemed to meet the gaze of the caftanned stranger, though what they were to each other I couldn’t begin to imagine. Perhaps he was merely remembering. He used to like to stand here when I was a little girl and watch me playing on the leapfrog tires; when I returned indoors he would pat my head and call me the Queen of England.

He smacked his lips—I could hear the false teeth clacking—and breathed deeply. “So tell me, Shula. Are you still teaching?”

“Lecturing,” I corrected. “In biblical studies.”

“And singing?”

“Oh, no. I gave up singing long ago.”

“A pity. You were such a lovely singer.”

Saul himself had missed his own vocation. He was ten years retired now from his teaching post, living in an apartment of legendary squalor beside the Sea of Galilee, whose calm waters had held him mesmerised for more than half a century. And yet of all the family it was he, perhaps, who had loved this house the most. Now he had ridden down like a white knight from the north, to stand guard over its benighted walls.

“We all become teachers,” he remarked cryptically. “None of us do the thing we’re meant to do. Anyway,” he added, with a sharp turn of voice which startled me, “I know why you’ve come.”

“Oh—and why is that?”

“It’s because of the Codex,” he said, and turning away, began shuffling back indoors. I made after him; he seemed to have abdicated from some kind of standoff, and when I glanced across the square again, the sidelocked stranger was no longer there.

Reproduced with the permission of The Toby Press.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply