Issue Archive

Profile: Adin Steinsaltz

Whether describing his inspiring belief in the Jewish people or his bleak vision of their future, this rabbi, writer and education activist embraces knowledge as a route to Judaism.

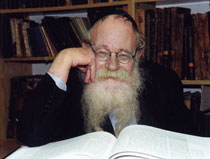

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz doesn’t look much like an adventurer. An untrimmed snowy beard sprouts below his fair cheeks; glasses, twinkly eyes, a black kippa and pipe complete his grandfatherly countenance and, despite his crisp blue shirt, there is something rumply and comfortably sedentary about him.

But the territory he has set his sights on conquering is one of the deepest, stormiest and most difficult to navigate: the “Sea of the Talmud,” the apt traditional description for the vast realm of what Steinsaltz calls “holy intellectualism.”

Since 1965, when Steinsaltz founded the Israel Institute for Talmudic Publications, he and his staff have been translating and reinterpreting the Talmud into accessible Hebrew: 38 volumes have been completed, with the last 5 tractates scheduled over the next two to four years. The Hebrew has so far been translated into 22 volumes in English, 15 in French, 4 in Russian and 2 forthcoming in Spanish. His interest in the Talmud stems from a scientific quest that places knowledge above all. Indeed, the credo he has popularized, “Let My People Know,” embraces knowledge as the route to Judaism and the root of Jewish passion and experience. In 1988, Steinsaltz received the Israel Prize, the country’s most prestigious award, for his translation and commentary on the Talmud.

His ardent belief in the inherent glory of the Jewish people has been his inspiration. “There is a very short sentence: ‘I am a Jew,’” says Steinsaltz. “This short sentence has two possible melodies. One melody is: I have hemophilia, it’s not my fault, but I got it. I’m surely not proud of it; in fact, I’d do whatever I could to get rid of it. The second melody is: I am a royal prince. I inherited it. It’s not my fault, but I’m rather proud of it and I won’t marry a commoner if I can avoid it. What I’m trying to do all my life is just to change the [first] melody, because the words can hardly be changed.”

Among his 60 books on topics from social criticism to mysticism are his two newest: We Jews: Who We Are and What Should We Do? addresses contemporary sociological issues from the perspective of a Jewish family; and Learning From the Tanya is the second volume of a commentary on the kabbalistic work that is a primary text of Chabad hasidism (both from Jossey Bass). This fall, Perseus Books is releasing editions with new material of his classics, The Thirteen-Petalled Rose: A Discourse on the Essence of Jewish Existence and Belief and The Essential Talmud.

Beyond books, he has founded a track of Mekor Haim schools in Israel that include an elementary school, high school and post-high school hesder yeshiva that blend Jewish learning with an open-minded curiosity about the world. (A hesder yeshiva is a five-year program combining Israeli Army service with Jewish study.)

“He has taken Jewish texts that were unreachable, untouchable, unteachable and opened them to the public,” says his 31-year-old son, Rabbi Meni Even-Israel, educational director at the Steinsaltz Center in Jerusalem, which houses Steinsaltz’s offices, library, archives, research institutes, educational initiatives and lecture space.

Built in 2003, the center in nahlaot rises above winding residential streets, hanging laundry and unavoidable mewling cats. Seated behind his desk, a computer and an assortment of texts in front of him, Steinsaltz downplays Time magazine’s description of him as a “once-in-a-millennium scholar,” portraying himself instead as “one of the less interesting members” of an extended family of colorful second and third cousins that includes a C.I.A. agent, a general at the Pentagon and a representative of the Communist Party in the Brazilian Parliament. His own family, he suggests, mirrors the diversity of the Jewish people. His voice is low, almost whispery, his English heavily inflected with Hebrew and Yiddish (his first languages), his tangential stories spinning responses as circuitous as a Talmudic argument.

“My children used to ask, ‘What are you doing at work?’” he says. “It’s a terribly boring thing. I sit with a number of papers in front of me—clean papers—and I dirty them, again and again and again.” But, he admits later, “in so many ways I’m going for very long journeys throughout time and space, enormous journeys. There are pieces of the past, present and… future…pieces of geography and history…. In that sense, I live in a very fascinating world.”

He has taken great physical journeys as well. He has “little wanderlust,” he says, to leave his native Jerusalem (he was born there in 1937 and has written about it poetically and prolifically); but to expand the boundaries of Jewish knowledge he has traveled to Jewish communities from Australia to Siberia. In 1989, he opened a Russian branch of Mekor Haim, the first Jewish institution to receive official recognition in the former Soviet Union, and later established teacher-training seminars and leadership institutes there. In the United States, Britain, Israel and the former Soviet Union, the Aleph Society helps propagate his teachings.

“He is an extraordinary human being with a complex, wise and subtle message,” says Margy-Ruth Davis, executive director of the Aleph Society in New York, who has worked with him since 1988. “People are attracted to him because they sense he is a window to something else. Others see him as holy.” She recalls an incident in which a Russian portraitist unveiled a sketch of Steinsaltz, only to hear from the rabbi, “That picture is not me. I don’t think of myself in that way.”

“He had depicted holiness,” says Davis. “The rabbi thought of himself as a more lively, active person.”

“He models a kind of scholarship that is seriously Jewish and in conversation with the world,” says Jay Michaelson, a doctoral student at Hebrew University of Jerusalem researching Chabad and the chief editor of Zeek: A Jewish Journal of Thought and Culture. “Even if you don’t embrace his traditional viewpoint, a lot of his teachings are timeless.”

Steinsaltz is not without his critics. In How Adin Steinsaltz Misrepresents the Talmud (University of South Florida), Jacob Neusner, professor of religion and theology at Bard College, disparages Steinsaltz’s view of the Talmud as a stream-of-consciousness dialogue instead of a highly organized presentation. The right-wing Orthodox, who have criticized the editions for not following the page format of the Vilna Talmud, are threatened by some of his progressive perspectives and even mounted a massive campaign against him when they perceived him as a “stand-in” for the Lubavitcher Rebbe, says Davis.

Steinsaltz’s bleak vision of the Jewish future can be alienating—or a spur to action. He talks about singles who sacrifice family for career and low birthrates that make for disastrous demography. The global state of the Jewish people, he says, is like a “high-level Roman suicide. People went into a warm bath and slit their wrists and lay there quietly, nicely, and the blood is dripping, and it is not painful. They become drowsy and just die.”

Jews in the diaspora have to either give up or rebuild Jewish life, a massive endeavor: “People would have to put their souls where their money is,” he writes in We Jews. “It doesn’t mean there is no hope,” he says. “That’s why I’m fighting. That’s why I have no time to write nice novels, which I would like to do. I have practically no time for hobbies.” He is still a fast and voracious reader, but his sculpting, drawing and carving (“I was one of those arty people”) have all been abandoned.

Steinsaltz’s father, a mason who dabbled in politics, came to Palestine as a pioneer in 1924 from a town along the Poland-Lithuania border; his mother, who worked as a seamstress, came from a similar background. Raised in a secular but proud Jewish home, Steinsaltz decided in his early teens to pursue a religious life. “I am a skeptic,” he explains. “I was skeptical about nonbelief.”

He studied science at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem before receiving rabbinical ordination. Unafraid to try the unorthodox, Steinsaltz established experimental educational institutions and became the youngest school principal in Israel at age 24. More recently, he was named head of the controversial, newly reconvened Sanhedrin, the 71-member ancient court of Jewish law, which hopes to examine issues from agunot (women refused a divorce by their husbands) to the reestablishment of the Temple. “If I have to, I will be alone,” Steinsaltz declares. “I’m not afraid to be the ‘other.’”

His wife of 40 years, Sarah, a psychologist, was born in Samarkand to a family that fled the Nazis. Esti, their oldest child, directs shelters for religious women who are victims of domestic abuse; Meni is the middle child; and Amehaye (an acronym of his four names), the youngest, teaches Jewish studies. The Steinsaltzes have 10 grandchildren. His own name, Adin (gentle in Hebrew), taught him to be anything but, creating a fierce passion that others might not realize masks his compassion, says Davis.

Steinsaltz has always had a deep connection to the Lubavitcher Rebbe. In 1991, the Rebbe asked Steinsaltz (meaning salt stone) to change his name using the Hebrew even (rock or stone). After Meni was diagnosed with acute leukemia at age 15, and following the custom of changing a name to protect the sick, Steinsaltz chose Even-Israel, Rock of Israel, from Jacob’s blessing to his sons: “Archers bitterly assailed him…. Yet his bow stayed taut, and his arms were made firm by…the Shepherd, Rock of Israel (Genesis 49:23-24).” Steinsaltz remains the “trademark” name.

Meni remembers his father’s vigil at the hospital: “He was there with me almost every night for three months. Seeing him in the middle of the night in the nurse’s room, smoking his pipe and writing notes, on one side showed the ultimate care for a child, on the other side, reflected how immersed he is in the intellectual.

“We had the pure freedom to choose our own religious and spiritual life,” he continues. “My grandfather used to say being an apikorus, a heretic, was better than being an am ha’aretz, an ignoramus.” Emphasizing the intellect comes at a price, he adds, describing his father as “reserved and disciplined” and recalling that he was almost never home.

Steinsaltz’s own health problems have contributed to the intensity of his work. He has Gaucher Disease, an enzyme-deficiency disorder. “He does more because every moment might be his last,” says Meni. Like most of us, he says, his father is a beinoni, the in-between man described in the Tanya, a Jewish spiritual text, who struggles to balance good and evil: “The Tanya says never give up. There’s no end to your ability to fix and be better. That’s what he’s trying to do.” —Rahel Musleah

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply