Issue Archive

The Arts: Memory Gets a New Home

Yad Vashem has built an ambitious history museum to try to explain the Holocaust to a world that will one day be without living survivors.

When renowned architect Moshe Safdie designed the new Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum, his stated intention was to take visitors on a journey from darkness to light, from descent to elevation.

And that is precisely the inevitable way to experience a walk through this structure, an elongated prism-like building that begins above-ground, then tunnels through the earth of Jerusalem before emerging again. As Safdie explains, it bursts “out toward the north, a volcanic eruption of light and life.”

Standing outside the new building, at the outdoor approach to the entrance in the structure’s side, the absence of Jerusalem stone is striking. The municipality requires all buildings be surfaced with the light amber-colored rock. But as a special dispensation from the City of Gold, Safdie turned to what he terms “naked concrete,” a gray unfinished surface suggesting a fate gone wrong.

Visitors, who enter the museum’s long, triangular main hallway via a bridge from the Avenue of the Righteous Among the Nations, immediately observe both ends of this marvelous prism. From the dimly lit start, the bright finish—a massive three-sided window framing the rolling hills and pine forests of the capital of the Jewish state—awaits like an enormous surreal projection. In between is an unfolding history of World War II, part of Yad Vashem’s attempt to understand the Shoah and interpret its meaning.

That task has always been monumental. the vast 45-acre Yad Vashem complex atop the Mount of Remembrance in Jerusalem already includes the International School for Holocaust Studies, the International Institute for Holocaust Research, archives, a library and a host of museums and memorials.

However, to help visitors comprehend the Holocaust in a world that will one day contain no living survivors, Yad Vashem decided to create an ambitious new home for the largest Shoah-related collection worldwide. At a cost of over $40 million and 10 years in the making, the museum houses over 2,500 artifacts, testimonies, photographs, film clips, works of art and music. Israeli researchers have been amassing these items since 1953, when the Knesset formally established the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority.

The objects, spread across 45,200 square feet, are wide- ranging. Many are simply astounding in their banality: Nazi Monopoly-like board games reward players for catching the most Jews, and anti-Semitic bric-a-brac including miniature beer steins portray Der Sturmer-inspired caricatures of Jewish men. At the other extreme, there are truly horrific items: calipers used to measure skulls according to Nazi racist theories, a stark wooden bunk where rows of starving death camp inmates shared a thin blanket for the night, soiled striped uniforms marked with triangles to represent the nature of one’s internment—Jewish, political, gay.

Laden with these objects, the path through the museum’s central corridor, which runs through the entire building, appears direct. However, horizontal barriers, filled with images, objects and video screens, create an unusual sort of obstacle course. Like exaggerated cracks in the sidewalk, these recessed channels, which Safdie calls “seizures,” bisect the corridor. They block a linear progression down the hallway, instead creating a serpentine path that guides visitors into nine adjacent galleries.

A 10-minute video installation by artist Michal Rovner is the first object in the corridor. Entitled Living Landscape, it depicts Jewish life before the Holocaust captured by visitors to Europe. “I took different film clips and blended them into one background,” Rovner explains, “just as the Jews blended into the fabric of life in the countries where they lived.”

Ahead, in both the hallway and the galleries, nearly 100 video screens await, displaying footage shot before and during the war, as well as new survivor testimonies and short documentaries produced for the museum. Among the last of them is the story of Shoshana Roshkowski, who survived the war only to plead for an abortion when a doctor told her she was pregnant.

“I can’t hear a baby crying,” she recalls telling the doctor. “I heard the babies screaming in Auschwitz. I don’t want it.” She had no money for an abortion, so when she returned home, she laid a wet towel across her stomach and pressed a hot iron against it. She lifted heavy objects, anything to cause the baby to miscarry. Nothing worked and she delivered the baby.

“When they brought him to me and I saw him alive, I thought of how I had wanted to kill him and prayed that God would let me keep him,” she says. As the days passed, she took him to a mass grave and told him, “Moshe, when you grow up, Mommy will tell you so many things. How many times your mother stood in the selections. How many times your mother jumped from row to row in order to stay alive. I’ll tell you everything.” But, she continues, “when he grew up, I didn’t talk to him about it at all. We, the Holocaust survivors, didn’t tell our children.” The hallway floor reaches its lowest point at an extensive miniature model that shows a cross-section of the gas chambers at Auschwitz. Like battalions of bleached toy soldiers, a sea of tiny victims stand alert, awaiting their fate. In adjacent structures, another group, the Sonderkommando, operate the crematoria until their murder is scheduled. The entire scene is stark white, suggesting the angelic innocence of the victims.

The self-contained galleries, designed by artist Dorit Harel, are filled with multimedia presentations that detail the Holocaust chronologically. They buttress the museum’s central corridor from either side, and the experience of repeatedly moving back and forth from the long hallway and through these galleries mimics the motion of sewing or weaving. As visitors proceed, they symbolically thread themselves into the spine of the museum. The detours then become as vital as the main route, allowing travel through the many chapters of the Holocaust. And yet, visitors must repeatedly pause to form their own impressions each time they cross the corridor to enter another gallery. Each gallery focuses on particular historical events. The first, entitled “The World That Was,” details the rise of the Nazi regime in 1933, anti-Semitism in Europe, persecution and ultimate displacement of Jews as social outcasts. The second gallery focuses on the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, anti-Jewish policies instituted in occupied Poland, forced labor and the plundering of Jewish property. The next gallery takes the uninitiated into the world of the Nazi ghettos—Lodz, Warsaw, Theresienstadt (Terezin in Czech) and Kovno, as well as occupied Western Europe and North Africa.

The Terezin section is filled with tragic examples of the loss of young life and resilience in the face of grave conditions. Visitors can see the artwork of Petr Ginz, who, at 14, was deported to the ghetto, where he edited the youth paper Vedem. A short biography explains Ginz’s dream of becoming a scientist or an artist. Alone for two years, his sister Eva eventually joined him in the ghetto; both their pictures are displayed here. Months after their reunion, in September 1944, Ginz was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, and he died there. In the many stories, poems, articles and paintings he left behind, Ginz expressed a rich inner world. When Israeli astronaut Ilan Ramon took his fatal flight aboard the space shuttle Columbia in 2003, he brought along a facsimile of Ginz’s drawing Moon Landscape, which unfortunately is not exhibited here.

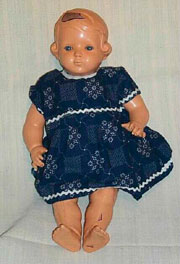

A doll belonging to 9-year-old Vera Bader is displayed with a brooch and a talit. She was deported to Terezin in 1943; the only thing she wanted to carry was the doll, which angered her brother, Jiri. He snatched the toy and threw it to the ground, breaking its head. Jiri, whose bar mitzva was celebrated in the ghetto, was murdered in Auschwitz along with his father. But Bader’s mother succeeded in hiding her daughter. When they were liberated, Bader and her mother took with them the broken doll, a brooch given to Bader by a good friend as a keepsake and Jiri’s bar mitzva talit.

Displayed near these objects is a Monopoly game made in the Terezin graphics workshop as part of the ghetto’s underground activity. It entertained children and taught them about life behind locked gates.

Subsequent galleries depict the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 and other critical turning points in the war, including the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, the Nazi implementation of the Final Solution in all of Europe and North Africa and the deportations to the extermination camps. The formation of the Jewish underground of resistance, Jewish partisans, Righteous Gentiles and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising stand in stark contrast to the silence, indifference and hostility of the free world.

In latter galleries, visitors learn of the inhumane conditions of the camps, the notorious death marches near the war’s end and survivors’ struggles to return to normal life postwar, in displaced persons camps, Israel and other countries. At the end of the museum’s long corridor is the Hall of Names. It is among the most poignant interpretations of the verse from Isaiah 56:5 that inspired the institution’s establishment: “And I will give them in my house and within my walls a memorial and a name (yad vashem)…that shall not be cut off.”

The Hall of Names is a circular room capped by a dome lined with photos and names of nearly 600 victims. In the center, these images reflect into a pool of water hewn into the bedrock below. Along the circumference of the room, shelves support binders containing Pages of Testimony, documents with the names of survivors and some biographical details.

Because nearly half of the Shoah’s six million victims remain anonymous, great lengths of shelves remain empty. With nothing to hold, this void calls out for the names of the unknown. A valuable public service, Pages of Testimony can be submitted online (see box at right).

To make room for the new edifice, the old history museum has been partially torn down, though some parts are used for storage and office space.

Aside from its visual magnificence and greater exhibition space, the element that distinguishes this latest addition to the Yad Vashem campus is the voice of the individual. Most Holocaust-era documents and film footage stem from official German sources and portray victims through the eyes of the murderer. These materials depict Jews “as vile and humiliated subhuman creatures,” explains museum curator Yehudit Inbar. “The way Jews experienced these events cannot possibly be understood using these materials alone. We decided to use these photographs and film clips [not only] as the framework narrative of what happened, but to search for ways to tell the Jewish story.”

As a result, some 90 accounts of specific individuals are integrated into the museum’s narrative through the display and description of personal belongings. Even something as seemingly benign as a button or a broken toy takes on meaning as each complements photographs, audio and video testimonies, drawings and quotes from diaries and letters.

The exhibits portray murder victims and survivors, children and adults, partisans and righteous gentiles, displaced persons and refugees. The museum gives names, faces and voices to the absent. It preserves evidence of these horrors to refute revisionism in future generations that won’t ever have the opportunity to meet Holocaust survivors and hear their stories firsthand.

“It is impossible to understand the Holocaust and absorb its meaning without learning about those who were most directly affected: the victims and the survivors,” says chief curator Avner Shalev, who also serves as chairman of the Yad Vashem directorate.

Yad Vashem’s stated aim is to “meaningfully impart the legacy of the Shoah for generations to come.” If measured by foot traffic alone, the new museum is already achieving its goals to educate, memorialize and underscore the need for a Jewish safe haven. In its first six months of operation, from March to September 2005, more than 600,000 people visited. At Yad Vashem, just as during World War II, secular and ultra-Orthodox visitors, and every variation in between, are bound together in a shared past.

The exit from the history Museum leads to the Holocaust Art Museum, one of a number of new buildings designed by Safdie that are part of the redesign of the entire Yad Vashem memorial complex. The art museum contains the world’s largest collection of art created in ghettos, camps, hiding places and any other place where artistic expression was nearly impossible. It is also home to the first computerized archive and information center on Shoah art and artists.

In addition, there is a new entrance to Yad Vashem, a beautiful, airy Visitors’ Center and an Exhibitions Pavilion, which has rotating displays of art and sculpture.

The new Visual Center, funded by Daniella and Daniel Steinmetz and Steven Spielberg’s Righteous Person Foundation, offers film screenings; it plans to become the world’s most comprehensive resource center of film related to the Holocaust. A Learning Center allows visitors to explore Shoah themes and related moral dilemmas through directed and independent learning, and an elegant, functional synagogue showcases beautiful ritual items rescued from destroyed synagogues in Europe.

One of the final pieces in the history museum is a video-art installation by artist Uri Tzaig, String, displayed in the “Facing the Loss” gallery. A series of inspirational quotes are projected onto a wall, such as this one from Warsaw Ghetto poet Wladyslaw Szlengel: “Sometimes the journey takes five and three quarter hours; sometimes the same journey lasts a lifetime, until death.” The work suggests the human spirit endures despite the tragedy of war.

Tzaig gleaned this material from original manuscripts, diaries, letters, notes and memoirs written by Jews during the Holocaust period and afterward by survivors.

In one part of the piece, a “virtual” album with turning pages displays the manuscripts in their original handwriting. Another wall shows floating letters that occasionally combine to form words and sentences, thoughts and reflections. The letters seem to dart through a moving spotlight, which echoes the spotlights used in the camps.

“This work symbolizes the human spirit that survived even in the inferno,” says Tzaig. As one anonymous quote states, “Even though my written Hebrew is broken and questionable, I cannot but write in Hebrew, the language of the future, because I will use Hebrew as a Jew standing proud in the Land of Israel!”

Throughout a visit to Yad Vashem, but perhaps most of all from the new history museum, we emerge with a tangible realization of a Jewish homeland. The triangle-shaped window at the hall’s end reaches up to the sky, revealing a breathtaking view of the Jerusalem horizon—a powerful image of hope.

On departing this memorial of the Jewish people, we not only leave with an awareness of our individual relationship to this devastating event, but also with a unique sense of the place that welcomes Jews from every corner of the earth.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply