Issue Archive

Chinese Jews: Reverence for Ancestors

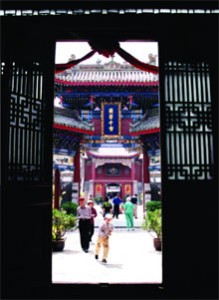

Gates of the Ancients Interior of a museum complex in Kaifeng that houses models and paintings of the historic city.

Heirs of the once-great Jewish community of Kaifeng are looking at their past and hoping, with help from Israel and Jews worldwide, to reclaim their heritage.

Judaism seems to have vanished from the city of Kaifeng, situated on the fabled Silk Road between China and the Mediterranean. Once, a small but thriving Jewish community existed here centuries before Marco Polo, the great Venetian explorer, traveled through China; a thousand years of assimilation into China has dimmed the Jewish light in the Far East. Yet some sparks remain. “I am a member of the Jewish people and I want to go back to my roots,” says 19-year-old Jin Jing in fluent English.

Though relatively tall by local standards, Jin looks like a typical Chinese teenager—city residents who are descendants of the Jewish community are generally indistinguishable from their neighbors. However, Jin’s cotton top is adorned with stylized Hebrew letters, and when asked about her knowledge of Hebrew, she replies shyly: “Ani lomedet Ivrit be’atzmi babayit.” (“I am learning Hebrew on my own at home.”)

An estimated 500 to 1,000 city dwellers claim Jewish ancestry, preserving some sense of their past through a mixture of loyalty and nostalgia. However, only 40 to 50 of them take part in Jewish activities. Whether more would join if it were clear they would not incur official displeasure is difficult to gauge in a country now just emerging from half a century of one of the most repressive dictatorships of the modern era. (Capitalism may be the economic order of the day in China, but religion is still under strict police surveillance. Roman Catholics are banned from contact with the Vatican, and forced-labor camps await active members of the Falun Gong, a Buddhist sect.)

With no official communal organization and a local synagogue that fell into rubble about 150 years ago, there is little to help those interested in Judaism become more involved. Those who actively affirm their identity do so discreetly, though they are extremely open with visiting Jews.

Nina Wang, another 19-year-old who speaks English, concedes the community knows little about Judaism. “But,” she insists, “I feel Jewish. My mother told me that I was Jewish and we keep some habits of the Jews such as respecting Shabbat.”

According to Wang, the community does not eat pork or mix meat and milk. Virtually all other manifestations of their Jewishness are recent imports gleaned from information brought to them by visitors.

Prayer books and Jewish instruction manuals in Chinese are sent from abroad and studied by a dozen adults and half a dozen children in sessions held about twice a week in private homes. This past year some 40 people gathered for a Passover Seder, complete with matza they had baked themselves. The Haggada was read in Chinese, since the only Hebrew prayers they have mastered are some blessings for Shabbat.

“We want to know more about Judaism because it is our culture and origin,” Wang explains.

Most members of the community live on or near Teaching the Scripture Lane, an ancient hu-tong (small city lane) named about a hundred years ago for the area where many Jews once lived.

The Zhao family resides in a simple two-room home on the hu-tong. They warmly receive visitors and offer for sale local-style papercuts adorned with Chinese letters, menoras and sometimes the words “I love Israel.”

The now-deceased family elder, Zhao Ping Yu, was the living memory of the community. He met with Western and Chinese researchers who trickled into Kaifeng after the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976. His 80-year-old widow, Cui Shu Ping, proudly shows visitors clippings about her husband from Western publications.

Before the Communist takeover of China in 1949, about 20 percent of the Kaifeng Jews were shopkeepers; the rest were craftsmen, shop assistants, teachers and blue-collar workers.

The revolution, however, eliminated ownership of private property, and today, like many city residents, most work in factories or as civil servants.

Canadian businessman David Adler was moved to tears when he spotted the familiar blue-and-white tzedaka box and a prayer book left by previous tourists in the home of another Kaifeng Jew.

“It was all they had, their only material connections with Judaism, and they displayed them with pride,” Adler said. “It just took my breath away… They were calling out to us to renew their ties with Yiddishkeit.”

There are numerous obstacles in the way of those seeking a return, the least of which are poverty and ignorance. The main difficulty is that the community had adopted Chinese patrilineal traditions; as far as Orthodox Judaism is concerned, they are no longer Jews.

“We know we will have to relearn many forgotten things and will have to convert,” says Jin. “But we are ready for all difficulties because we wish to be full Jews again.”

Jin’s father, Jin Guang Zhong, 45, says through an interpreter that he knows one Hebrew word, “Hadassah”—the name he and his wife gave their 8-month-old daughter.

The proud father is inspired by his brother Jin Guang Yuan. He and his wife, Zhan Yin Ling, were officially accepted as Jews under the names Shlomo and Dina by a religious court in Jerusalem last June and remarried in a religious ceremony in September.

Their conversion followed that of their 21-year-old daughter Jin Weng Jin, who was renamed Shalva.

“My uncle is trying to help us go to Israel,” says Jin Jing. “He also sends us prayers we can learn to help us in our return to Judaism.”

The Jins in Israel are the first Kaifeng Jews to return officially to Judaism, helped by the Jerusalem-based Shavei Israel organization, founded by Michael Freund, which reaches out to long-lost communities.

Kaifeng lies on the banks of the mighty Yellow River in Henan Province, nearly 700 miles southeast of Beijing. The bustling metropolis attracted Jewish merchants from Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) during the reign of the Song dynasty more than 10 centuries ago. Today, the streets are still busy but most residents are impoverished.

The Jews were officially allowed to settle in the city in 960 C.E., and in 1163, they built the large Purity and Truth Synagogue, whose replica in miniature can be seen at Beth Hatefutsoth, the Nahum Goldmann Museum of the Jewish Diaspora, in Tel Aviv.

But the subsequent moving of the capital to Beijing, and generations of wars, poverty and isolation from other Jews, caused the community to wither away after peaking at 5,000 people in the 17th century.

The Jews of China were “rediscovered” by the West in 1605 when, during a visit to Beijing, community leaders Ai Tian met Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci. Christianity was unknown in China, and Ai thought the missionary was a fellow Jew because they shared biblical references.

Ai wanted Ricci to come back to Kaifeng with him to become the community’s rabbi until he realized, horrified, that the Italian was seeking converts to another religion.

Over the ensuing centuries, the community resisted repeated conversion attempts by Jesuits and other missionaries fascinated by this small repository of Judaism. The city’s last rabbi died in the mid-19th century, leaving behind a community where religious practices had long been diluted by intermarriage. Even the post of rabbi had at that time become hereditary. The synagogue had also been destroyed for the 5th or 6th time in its history by floods that regularly ravaged the city and threw the entire population into long periods of poverty.

Their situation desperate, the Kaifeng Jews appealed to Western Jewry at the start of the 20th century, asking for teachers to help them renew their knowledge of Judaism and reconnect them with the Jewish world. A Society for the Rescue of Chinese Jews was formed in 1900 by the Sefardic community in Shanghai, but no action was taken.

When Communist forces took power, they imposed an atheistic regime. This should have spelled extinction for Jewish identity in Kaifeng, but with an inspiring tenacity, Kaifeng Jews managed to keep some knowledge of their past alive.

Today, the outlook for the community is more hopeful. Greater tolerance from China’s new rulers who are remaking the country into a leading economic power and the Kaifeng municipality’s attempt to remake their city into a popular tourist destination has allowed for more Jewish expression.

Chinese authorities welcome foreign Jews to Kaifeng, offering a tour of the city (see box for contact information). Tours start in the boiler room of Local Hospital No. 5, the former synagogue site, and a large engraved cover, the remains of a well. Said to be a last remnant from the synagogue courtyard, the well allowed Jews to refresh themselves before services.

Synagogue relics such as a massive stone water jar and a tall stone stele, both dating to 1489, are housed in the Kaifeng Municipal Museum. (Other artifacts, such as several Torah scrolls, prayer books and a memorial book, were sold and have been preserved in museums around the world, including the British Museum in London and the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada.)

The stele is one of several inscribed with the history of the local Jewish community that had been placed in the synagogue. It refers to Yi Tzu Leleyeh, a Chinese transliteration of Israel or Israelites. The term currently used for Jews in Chinese is Yo-tai, believed to come from the Dutch or German words for Jew (Jood and Jude) and introduced into the language around 1840 together with other Western influences.

The stele also describes how the Jewish families came to have Chinese patronymics. The surnames Ai, Gao, Jin, Li, Zhang, Shi and Zhao were conferred on the Jews by a Ming emperor who found Hebrew names confusing. The seven are typical Chinese surnames. Two, however, Shi and Jin, meaning stone and gold respectively, are also common among Western Jews.

Jewish visitors are also brought to the Riverside Scene Park of the Qingming Festival, a sprawling cultural theme area based on a Song dynasty painting with models of period streets and buildings. The park includes a small Jewish museum, open to foreigners only.

On display are a large model of the former synagogue and paintings by Chinese artists of what might have been the early history of the Jewish community, with Jews in biblical garb arriving on camels across the forbidding Gobi desert.

Officials at the municipal museum say Israeli ambassadors have visited the room where artifacts from the synagogue are shown. But the Kaifeng Jews relate that no Israeli diplomat has ever sought them out and that their efforts to enter the Israeli Embassy in Beijing have been rebuffed. Israeli officials claim the issue is complicated and prefer not to discuss it publicly.

Shalom Solomon Wald of the Jerusalem-based Jewish People Policy Planning Institute, a body with ties to Israeli authorities and headed by Dennis Ross, former United States special envoy to the Middle East, takes a tough attitude.

“Jews are often parochial and easy victims of exoticism,” explains Wald, who wrote China and the Jewish People: Old Civilizations in a New Era (Gefen), a study of the relationship between Israel and the emerging superpower.

“Why get excited about a little group in China when there are a million youths in America with Jewish mothers but no interest in being Jewish? That is a real existential danger for the Jewish people and Israel’s future,” he adds.

Wald also points out Beijing’s extreme touchiness about a religion with foreign ties. “It may seem coldhearted, but is it worth endangering Israel’s ties with an emerging superpower for the sake of a few hundred people?” he asks.

Michael Freund of Shavei Israel sees the situation differently. He is angry at the Israeli government, which, he says, “ignores” the Kaifeng Jews to ensure its economic and political ties with China are not disrupted.

A painting in the Qingming park Jewish museum shows the ceremony where, more than 10 centuries ago, Emperor Song Zhao Chuan Yin granted right of residence to arriving Jewish merchants, who prostrated themselves before him.

“You have come to our China but you may continue to respect and keep the traditions of your ancestors,” the emperor told them.

A thousand years later, some are trying to do just that.

“We failed the Kaifeng Jews 100 years ago,” asserts Freund. “Their continued tie with Judaism should inspire us and we should…maintain contact with them to show them they are not forgotten.”

Bernard Edinger, a New York-bred journalist, reported for Reuters for over three decades. He now lives in Paris.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Tiberiu Weisz says

All the info in this article is based on western perceptions but do they agree with Chinese sources? Not really. Here is what Chinese sources wrote about the Israelites:

1. The Kaifeng Stone Inscriptions (2006} a new translation of the stela from Chinese annotated in both biblical and Chinese history.

2. A History of the Kaifeng Israelites (2018). What is the Chinese words/characters for Jews in ancient Chinese literature. (NOT YOUTAI) . Who were the early Israelites who settled in china after the hurban? What did Confucius say about the Israelites? …. Translated from ancient Chinese literature.

Tony says

Hi I am Tony I am trying to contact the Kaifeng Jews in china or Israel can you give me a contact email or WhatsApp number to contact please