Issue Archive

The Arts: Photo Treasure in the Attic

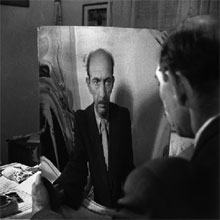

Press photographer Paul Goldman captured early Israel in his work. A traveling exhibit shows his portraits of a nation in the making.

It’s not your usual picture of a head of state: A white-haired, bare-chested, 71-year-old man in somewhat skimpy black bathing trunks doing a headstand on the beach. But that is the iconic image photojournalist Paul Goldman took of David Ben-Gurion in 1957. A triptych of photographs shows Israel’s prime minister balancing on his elbows, letting go and positioning his legs into the air at a right angle. A follower of the Feldenkrais Method (a system of movement, functioning and awareness), Ben-Gurion is said to have given a tongue-in-cheek reply to the question of his unusual stance: “I have to stand on my head so the State of Israel can stand on its feet.”

How the state got to its feet comprises the visual text of Goldman’s images, a hundred of which are on display at the Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion Museum in New York through January 20, 2006. Infused with an everyday heroism and pioneering spirit that define our perception of Israel, they tell the story of the state’s creation, from the British Mandate to the War of Independence, from the poignant arrival of Holocaust survivors and the trial of Adolf Eichmann to exclusive photos of Yemenite Jews in Aden. The images were originally displayed at the Eretz Israel Museum in Tel Aviv last year and will travel to the Sony Ericssohn Proud Galleries in London in February.

The exhibit unfolds like an old family picture album—its images enlarged and displayed by proud parents, only the family is the state and people of Israel. The black-and-white scenes are sorted by category: Refugees/Immigrants, War of Independence, Formative Events, Agriculture, Tel Aviv and Portraits. One after another, they assault the memory—or, for younger viewers, create it. Dancing the hora, laying a water pipeline in the Negev; ploughing fields, mining sand for construction—with camels, hoisting the Israeli flag. These were “tremendous national undertakings, done with so much pride,” says Time-Life photographer and Israel Prize winner David Rubinger. Rubinger’s own most famous image is arguably that of paratroopers at the Kotel during the Six-Day War.

Just starting out himself in the 1950’s, Rubinger admired Goldman’s ability to be everywhere. Goldman photographed formative military and diplomatic events presided over by Israel’s leaders, striking in their youthfulness: Ariel Sharon and Moshe Dayan with soldiers; Golda Meir watching a soccer match between Israel and the Soviet Union in 1956; Menahem Begin, arm outstretched, addressing a political convention; Moshe Sharett (Israel’s second prime minister) signing the Declaration of Independence.

Goldman “stood with his camera by the cradle of the state-in-the-making,” writes curator Shlomo Arad in the exhibition catalog. “The situations he recorded, the contexts and choices he made—are the threads of the elusive web that constitutes the collective memory of this nation. This is how we were. This is how we looked.”

Goldman worked in an era when crediting photographers was the exception rather than the rule. Born in Budapest in 1900, he came to Israel (then Palestine) in 1940 with his wife, Dina. They were interned as “illegal immigrants” in Atlit, near Haifa (one of the photographs in the exhibit shows a little boy in a too-big overcoat sitting on a duffel bag after disembarking from a train in Atlit in 1945). After serving in the British Army, Goldman struggled to find work; he was older than his colleagues and spoke poor Hebrew. He freelanced for international press agencies between 1943 and 1965 and was a close friend of fellow Jewish Hungarian Robert Capa (born Andre Friedman), one of the fathers of modern photojournalism. Goldman died destitute and almost blind in 1986, and his work was mostly forgotten.

Almost as fascinating as the images themselves is the story of how they came to be unearthed. In 2000, Time wanted the photograph of Ben-Gurion on his head for its millennium issue and asked Rubinger to track it down. Remembering that it might have been a Goldman shot, he contacted Goldman’s daughter, Medina Goldman Ortsman. In the attic above her kitchen in the apartment she shared with her mother in Kfar Saba were old shoe boxes with 40,000 moldering negatives, most taken between 1943 and 1965. Only a tiny percent had ever been published. Ortsman showed Rubinger a book her father had kept, meticulously listing each photograph in beautiful calligraphy in his native Hungarian. “I sat down with Goldman’s 93-year-old wife, and whenever I saw ‘Ben-Gurion’ I’d ask in German, ‘Was ist das?’ until I found the photo,” recalls Rubinger.

Several years later, a Michigan real estate developer and art collector named Spencer M. Partrich was looking to buy a photographic archive. A mutual friend knew about Rubinger’s find and brought the two together. Partrich bought the collection from Ortsman sight unseen. “I knew this was irreplaceable,” Partrich says. “Israel is a small country. We are a small people. This is truly a mirror of the moment. I felt very strongly it needed to be conserved.”

A Jerusalem firm is now restoring the photos, but 20 percent are unsalvageable, and 30 percent of the negatives will have to be peeled apart carefully. About a thousand pictures have been scanned so far and “we have not scratched the value of the archive,” says Rubinger. After the restoration began, the Eretz Israel Museum contacted Partrich to put together an exhibit from the collection in 2004, and Goldman’s remarkable account of early Israel has been on display since.

The images reflect the access Goldman had to Ben-Gurion in public and private settings. Paula Ben-Gurion allowed him to photograph her sweeping the floor of their home. On an even more personal level, when Goldman’s daughter was born he was at Ben-Gurion’s side. It was November 29, 1947, the day the United Nations voted to establish Jewish and Palestinian states. Goldman, who was covering Ben-Gurion, asked the leader what he should name his daughter. “Medina [state, in Hebrew], of course,” Ben-Gurion replied, “for they were born together.”

Goldman was more a journalist than a path-breaking artist, says Yeshayahu Nir, a professor in the department of communications and journalism at Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “He did not aspire to leave his personal mark or to be present in his photographs,” Nir writes in the exhibition catalog. “He saw the world with everyman’s eyes. It is this quality that made him the paradigmatic press photographer. He simply photographed what he saw, at eye level.”

That doesn’t make his work less sensitive or touching. His image of a little boy standing at attention, a “Buchenwald” patch sewn on his jacket, grabs at the heart. (The child is thought to be Israel Lau, now chief Ashkenazic rabbi of Israel.) An image of an Auschwitz survivor revealing the words “Feld-Hure” (literally, field whore, meaning the woman was forced into a military brothel) tattooed on her chest is no less shocking because of the wedding ring on her finger.

As many other photojournalists did, Goldman photographed the Syrian tank that penetrated Kibbutz Degania Bet during the War of Independence. But he also caught the kibbutz members in the trenches at a lighter moment, chatting amiably but ready to defend themselves. In fact, the tank became a symbol of the war because the kibbutzniks forced the Syrians back.

Goldman took a factual approach to the “essential dilemma of press photography,” as Nir describes it: deciding whether to “give preference to an emotional, shocking or moving image, or to a straightforward, informative one.”

“Photojournalists don’t aim to create impressions,” notes Rubinger. “They concentrate on recording the events…. You don’t think of political implications.”

But, he adds, “you can’t be a good photojournalist if you don’t have empathy…. The way you choose your position, angle, lens—all reflect your attitude.”

Not afraid to swim against the stream, Goldman captured Arab villagers being expelled from their homes in 1948, snaking in a long line across a field, showing what the new nation wanted to suppress. The Israeli newspaper Devar Hashavua published the image but captioned it, “Arab women with their children were returned to Arab territory.” Another image depicts Arab men behind a barbed-wire fence after Ramle’s occupation, crouching, stretching their hands out to receive water from Israeli solders. Operation Magic Carpet is remembered in Israeli folklore as a secret operation, says Nir, but in Goldman’s photos, British uniformed soldiers or policemen watch as Yemenite Jews board trucks peacefully in Aden.

Goldman’s photos mirror the essence of an era long gone, when helmeted British and Arabs in fezes watched camels parade by the King David Hotel in celebration of Jordanian King Abdullah’s 65th birthday. The only thing left today, Rubinger points out, are the stones of the King David. “That’s what makes photojournalism so great,” he says. “It captures a moment in time.”

“These old photographs,” says Nir, “invite us to assemble them, to remember, to try and reconstruct from them an entire picture, much like the reconstruction of ancient clay fragments into a whole jar.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] Rahel. “The Arts: Photo Treasure in the Attic.” Hadassah Magazine Dec. […]