Issue Archive

The Arts: Ingathering of Visions

Love of their Jewish homeland and concern for its people connect three artists whose works range from printmaking to landscapes to postmodern collage.

Like many who immigrated to Israel during the idealistic surge following the Six-Day War and the reuniting of Jerusalem in 1967, London-born printmaker Mordechai Beck sought inspiration in Zionism.

Today, rather than finding any idealized “universal” element in the present state of Zion, he bemoans the split between the religiously observant and those who are not. “Secular Israelis and the ultrareligious deny the universal element in their own tradition,” he says. It is such a paradox, Beck adds, that sometimes it takes an outsider to see what it’s all about.

Painter-poet Rifkah Goldberg, daughter of a London rabbi, has yearned since childhood “for a Jewish path that considers and includes the outside world.” Her decision to move to Israel in 1975, she claims, provided her with just that.

Born in a displaced persons camp in Italy and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, collagist and textile designer Chana Cromer came to Israel in 1972 after becoming involved in a progressive religious community that combines ideals of social justice and egalitarianism with religious observance. Most of the community moved to Israel and formed Jerusalem’s Kehillat Yedidya synagogue.

Working in three very different media, these olim have funneled a profound love of their adopted country and Jewish tradition into personal, often poignant, artistic statements about the society they live in.

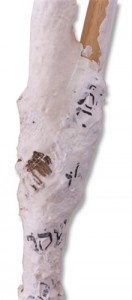

Cromer’s series “The Hollow of His Thigh,” which centers around Jacob’s struggle with an angel, was created while recuperating from falls in which she twice broke her hip; she acknowledges the experience made her more empathic with the prevalence of injury in her environment. (Her falls occurred when her two sons were in the Army. She says she “broke a hip for each one.”) Buttons, shells, nails and other “found” objects and sculptural textures make up part of her artistic arsenal. They form a kind of collage, or “garment,” for an examination of the human condition.

“I like the phrase [‘the hollow of his thigh’],” she confides. “The implication is of a wound deep within, a defenselessness in that area of the body. The touch of the hollow of the thigh does have sexual implications… The place of pain, that precisely is the area from which one can create and grow.”

Beck, who is also affiliated with Kehillat Yedidya, and Cromer are primarily inspired by biblical mythology. Both use protagonists such as Jonah and Samson, Jacob and Joseph to portray acute psychological struggles relevant to Israel’s present situation.

Beck studied at London’s Hornsey College of Art in the 1960’s, became a writer, then switched to printmaking after attending the Jerusalem School of Printmakers in 1988. He has recently created his most impressive works: three limited-edition small books, livres des artistes, that combine text and art: Song of Songs with calligrapher Izzy Pludwnski; an Ushpizin booklet comprised of seven invitations to each of the holy Sukkot guests who attend meals on each succeeding night of the festival; and the 16-pageMaftir Yonah with calligrapher David Moss. His books are at Yale University’s Sterling Memorial Library in New Haven, the Library of Congress in Washington and the Museum of Modern Art in New York (to see more of his work, visit www.mordechaibeck.com).

Beck sees his entire life and work informed by an inner tension that, he says wryly, “probably comes from the Jewish gene pool” and connects him to all the excitement and neuroses of “our crazy, mixed-up people.”

Full of tremendous energy, yet with a delicacy of line, Beck’s linocut of a heaving Big Fish facing a small human vessel on a tumultuous ocean in Maftir Yonah is expressive of Jonah’s inner conflict. Similarly, his two-toned Nineveh animals, in the same book, show a blurring of animal and human. Jacob, part of Ushpizin, shows the protagonist’s dreamscape. While Jacob himself lies flat on deeply pitted earth with only his head visible, behind him, in soft pastels, a toy orange ladder and yellow crescent moon hint at the celestial connection.

Cromer has a master’s degree in education from Boston College. She studied at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem and the Pratt Institute in New York. Her recent series “Covering Uncovering: Textiles in the Story of Joseph” looks at the biblical Joseph’s trauma. It was exhibited at Yale University’s Joseph Slifka Center for Jewish Life in 2004, funded by a Jewish Memorial Foundation fellowship, and there are plans for it to be shown again in the United States in 2006. The series relates not only to the persecution Jews have been subjected to throughout history, but to the plight of all underdogs, from foreign workers to Palestinians. A child of Holocaust survivors, the artist’s greatest fear is not of Jews becoming victims again. “I don’t want our society to do it to others,” she says.

While much of israeli art has tended toward the abstract, Rifkah Goldberg feels she must start with realities she sees before transforming them into “visions.” Goldberg’s subject is the changing landscapes, buildings and people of Jerusalem; they are her milieu and inspiration. Part of the pleasure of her expressive paintings is that many are of recognizable sites important to local history. Rather than the tourists’ Jerusalem, Goldberg focuses on buildings and neighborhoods in the process of demolition, emphasizing the struggle and pain of transformation. One study depicts what had once been a factory where ice was made for distribution to Old Katamon before people had refrigerators. Two others, Death of a Shop I and Death of a Shop II, portray stores that have given way to the light rail on Jaffa Road.

“The first time I got the idea to paint a building when it was being torn down was one Shabbat afternoon when I knew my marriage was breaking up,” she recalls. “I walked around the area of Mamilla, which used to be on the border between the old and new cities…. I saw a building with a roof half taken down. I decided to come back with a canvas the next day.”

For Goldberg, this was the start of a year spent painting houses being demolished to make way for the development of David’s Citadel, an exclusive residential area in the city. Theodor Herzl stayed in one of the houses that was eventually destroyed. The building’s stones were numbered for reassembly as a historic landmark, but sadly, she says, “this has not yet happened.”

Goldberg started painting flowers at Cambridge University (where she got a Ph.D. in biochemistry), moved to Israel and attended People’s University and Bezalel. She has amassed an oeuvre of over 300 paintings in her tiny apartment and frequently trundles off to various Jerusalem sites with easel, canvas and brushes. Citing among her influences Vincent Van Gogh for color and the British artist L.S. Lowry for eccentricity and character, Goldberg professes to find her mission in life in transmitting “the consolation of color.” However, what she does best is convey the sheer personality of man-made objects at the very moment of disintegration: trees and wild grass growing out of buildings; doors and windows leading nowhere; rusty, out-of-place objects such as chairs exiled from their original setting but stamped with the character of their owner. One especially dramatic work portrays the old Shaare Zedek Hospital complex. (Due to the main building’s historic status, it was refurbished and now houses the Israel Broadcasting Authority.)

She is currently working on a series called “At the Beit Frankforter Center for the Aged,” focusing on elderly people at the center. (Goldberg’s pieces are on view at the Artists’ house Gallery in Jerusalem and at www.israelartguide.co.il/rifkahgoldberg.)

While Goldberg finds transcendence in the particulars of her landscapes, Cromer sees it in more personal terms. She regards what she does “as a resource and source of strength that is beyond the fray—apolitical.” Cromer feels her art pieces “come from a different place, one of a deep involvement in the wonderful personal narratives in the Torah and their potential for telling us something about ourselves, our surroundings.”

Her passion for art and Torah led her to establish in 1992 the visual arts department of Israel’s first religious arts high school, Jerusalem’s Torah Arts Academy.

Cromer (www.chana-cromer.com) works in a variety of media—textiles, etching, appliqué, assemblage and painting. Her palette is at times colorful, at times monochromatic, always gorgeous. In “Covering Uncovering,” she uses layers of metallic pigment with gold, silver and bronze embellishment and transparent fabrics to capture light and express the multifaceted quality of spiritual realities.

Before beginning the project, Cromer recalls wondering if Joseph’s pit clothes should be ugly or beautiful.

“Joseph stripped of his coat of many colors presumably was cast into the pit naked,” she explains. “But perhaps there is a sense in which he was naked even before, that the coat was made up, according to mystical tradition, of seven veils of translucent light. Or does this allusion to his nakedness indicate his vulnerability?

“What is the pit but a prison?” she asks. “Joseph was stripped and flung into a prison twice, the second time at the instigation of Potiphar’s wife. How does that repetition of being victimized, for a man so powerful, make one feel? The pit represents a return. We’ve all been there, sooner or later. The pit is a place we all relate to.”

And creating work that people can relate to, that resonates with meaning inside and outside of Israel, is a goal that motivates all three artists.

Freema Gottlieb, Ph.D., is an author, freelance writer and teacher living in New York.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply