Arts

Feature

Arts: Art From Everything (Incl. the Kitchen Sink)

In one of Maira Kalman’s self-portraits, a lopsided pair of blue eyes peers out of a penciled face cradled by a fur-collared coat. Black galoshes ground her in the midst of walking. a The off-center vision reflects Kalman’s idiosyncratic perspective on the world, one that reveals itself in the heady parade of contemporary life she depicts, the family narrative she draws on and the boxes, rubber bands, tags and other seemingly mundane objects she both collects and illustrates.

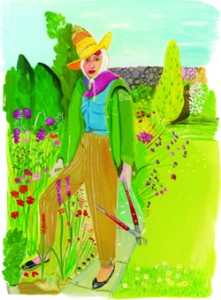

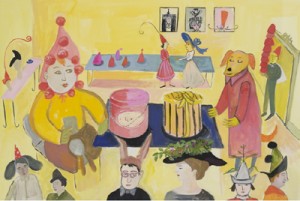

The self-portrait (I Saw Her) and two others—one a sketch in a brown Isaac Mizrahi jacket and the other a gouache painting with her dog, Pete, a sketchbook and pencil on her desk—open the exhibition of 100 illustrations entitled “Maira Kalman: Various Illuminations (of a Crazy World)” that runs through June 6 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia (215-898-5911;www.icaphila.org). The show then travels to the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco (415-655-7800; www.thejcm.org; July 1 to October 26); the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles (310-440-4500;www.skirball.org; November 16 to February 13, 2011); and the Jewish Museum, New York (212-423-3200;www.thejewishmuseum.org; March 11 to July 31, 2011). In this first major museum exhibition of her work, the illustrations wrap around a central installation of items that Kalman culled from her New York studio and home—ladders, suitcases, chairs, linens, an empty box collection. There are also tables filled with objects, including a display of 4 of her 12 children’s books and 2 adult books: an illustrated version of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style and a series of picture essays, The Principles of Uncertainty, based on an online New York Times column. She describes the objects as “tangible evidence of history, memory, longing, delight” in Principles. Other media are also represented: embroidery, photography, textile and performance, with four short films. Her December 2001 New Yorker cover, New Yorkistan, has probably brought Kalman the most name recognition. The cartoon map divides the boroughs into tribes: Pashmina on the Upper East Side; Taxistan, Irate and Irant in Queens; and other areas from Fattushis and Kvetchnya to Lubavistan and Botoxia. In the aftermath of 9/11, this collaboration with writer and illustrator Rick Meyerowitz provided much-needed laughter. “Kalman’s narrative art comes from her everyday observation of ordinary things…and profound events,” writes senior curator Ingrid Schaffner in introductory notes to the exhibition. For Kalman, a simple pink package tied with string beckons because of its strong boxy shape, alluring color and unpretentious utilitarian task that merge with a family memory: It holds bangles Kalman purchased on a trip to India for her daughter, Lulu. The box is both ordinary as well as a receptacle invested with emotion, meaning and mystery that endures beyond the fleeting moment. The original pink package is on display, with an index card that reads, “The box from India that may not be opened.” Kalman falls in love with things: She depicts the empty kitchen sink from the home of modern architect Le Corbusier, choosing not to show his studio but the porcelain fixture in which he washed his hands. “This light touch is typical of the humor that gives Kalman’s work its vitality and charm,” Schaffner writes in the show’s catalog. “Paradoxically, its lightness is also what gives her work the capacity to be so profoundly moving.” Thematically organized and following Kalman’s journalistic bent, the exhibition moves from the self-portraits to her mother; her children—Lulu Bodoni (named for a typeface she and her late designer-husband Tibor Kalman liked) and Alex Onomatopoeia (one of several middle names); and fictional and real dogs Max Stravinsky and Pete, respectively. The works drift to maps and places—New York, Tel Aviv, Paris, India—to dreams and portraits of people, including Tibor, who died in 1999 after a four-year battle with cancer. “What happens in my life is interpreted in my work,” Kalman says. “There is very little separation.” A sense of urgency permeates—the need to share a joke, a poignant moment—mirrored in the opening lines of Principles: “How can I Tell you Everything that is in My Heart. Impossible to Begin. Enough. No. Begin.” Schaffner has hung the illustrations in a linear band, hugging the perimeter of the rectangular exhibit space. The frames almost touch, flowing like a picture book, the works linked by narrative, color, form or image. A pink floor in A Dream in Venice connects to an embroidered pink dress and then to an illustration of a pink designer dress (Viktor & Rolf) at a Paris fashion show.  In a mural for the library of PS 47 in the Bronx (shown in a video installation), the letters of the alphabet are transformed into a commentary on language; for example, President Lincoln materializes in his black stovepipe hat a few feet away from H is for Hat. Flowers in the garden tended by Lady Birley (a famous gardener and wife of portrait painter Oswald Birley) reappear as the subject of a still life (Aalto Vase with Poppies), then recur in a portrait of German Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin and in a lavish table in The Herring and Philosophy Club. “One thing leads to another,” Kalman writes in Principles. “Flowers lead to books, which lead to thinking, then more flowers and music, music. Then many more flowers and many more books.” When Schaffner offered the exhibit for travel, she was surprised that three Jewish museums immediately accepted, since Kalman’s work is not intrinsically Jewish. Kalman memorializes her beloved mother, whose family fled pogroms in Russia and settled in Palestine. A blue, blob-shaped map shows her mother’s view of the world, collapsing it into a few randomly placed American states, Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and a fictional Lenin on the bottom, Canada a gray band at the top. Most of the remaining area is dismissed in a few words: “Sorry the rest unknown. Thank you.” Ladders, which she says appeal to her “emotionally, architecturally and playfully,” are scattered around. A pie safe labeled with the names of her grandmother, mother and sister holds 100 linens from around the world that Kalman has starched, ironed and folded (a favorite pastime), a loving symbol of domesticity. Kalman invites viewers to imagine the process by placing chairs in front of the chest. Two vitrines painted blue that Alex crafted when he was 13 encase 10 onion rings as well as 3 watches created by Tibor’s design company, M&Co (M for Maira). A framed onion ring hangs in the background of Kalman’s 1998 portrait of Tibor. Of M&Cos’ timepieces, one was inspired by a sketch Tibor spotted in Maira’s notebook, jauntily sporting only a few random numbers. Other cases hold spools of green embroidery thread, twine, language books (Teach Yourself Gujarati; Tulugu Without Tutor), a list of antidepressants, bobby pins, shoes and rubber bands. Kalman even cofounded a Rubber Band Society. Though it was based on “something silly and fleeting,” she recalls, it grew to hundreds of members. “It shows the nature of people to need connection,” she explains. The group, she adds, has since disbanded. She is adept at capturing the color and chaos of life. Couples kiss, men in fedoras scowl, people run with handbags in New York, Grand Central Station. “What did you expect?” and “I feel rotten” read placards and buttons in Annual Misery Day Parade; even dogs suffer from malaise. “What’s the point?” asks a pooch’s sweater.  Food and fashion divert Kalman endlessly, from American snacks like Snickers bars to jaunty hat wearers. There is English author and poet Vita Sackville-West (Virginia Woolf’s lover) in a black-rimmed hat above hooded eyes and a long nose. Another English poet, Edith Sitwell, sports a topknot hairdo. In Panache, an illustration from a forthcoming book called 13 Words (HarperCollins) with children’s author Lemony Snicket, customers in a hat store run by a baby try on black Elsa Schiapparelli shoe hats; rabbit ears; pointy red party hats; blue bonnets and a fez. A hatless dog waits on customers—or waits his turn.

Kalman travels with her camera and sketchbooks and documents everything she finds “tragic, enriching or compelling,” then uses the photographs as studies. The exhibit matches three picture bands with the final paintings. Above Museum Guard with Bow hangs a photograph of the same woman, a black bow in her white hair. To further introduce viewers to the process of the artist at work and as a reminder that the drawings were created for publication, several include erasures, Scotch-taped additions and notes to printers in margins. “My dream is to walk around the world,” Kalman writes in Principles. “A smallish backpack, all essentials neatly in place. A camera. A notebook. A traveling paint set. A hat. Good shoes. A nice pleated skirt (green?) for the occasional seaside hotel afternoon dance… Kalman has already traveled far—on assignment forThe New York Times and other publications or to visit family in Israel (she owns an apartment in Tel Aviv). A discarded chair on a Tel Aviv street and the city’s Bauhaus architecture turn up alongside an image of her aunt’s small kitchen, where Kalman sips tea and eats honey cake. Kalman initially set out to be a writer, but decided drawing would be a better way to tell her stories. She did not pursue formal art training. “I don’t like to say too much,” she notes. “Images and a few words convey my feeling about anything I see.” But the intersection of life, relationships, storytelling and literature is present in her work, both in numerous portraits of writers and in the overlap of writing and drawing. “Inscription, description, narrative, notation, quotation, painting and poetry all flow from the same brush, the same pen, and occasionally from the typewriter,” writes Schaffner in the exhibition notes. The typewriter in one of Kalman’s earliest works, R. Esterbrook Pens, pays tribute to cartoonist and icon Saul Steinberg, known for his portrayal of desktops as landscapes. Exaltation/Observations has simultaneously humorous, trivial and deep lists of items and questions written in Kalman’s calligraphic hand; one list, different cakes of interest, includes mocha cream and lemon pound. An actual coatroom claim check and toothpick are collaged to the paper. Recently, Kalman’s art has become more painterly, reminiscent of the work of Vienna-born Charlotte Salomon. Salomon died in the Holocaust but hundreds of her gouaches survived. Other artististic influences include Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, Jim Nutt and Fred Sandback. |

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply