Israeli Scene

Feature

The Rebranding of Umm al-Fahm

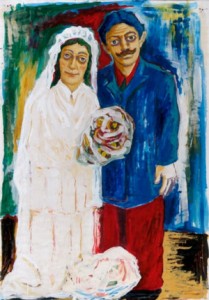

Courtesy of the Umm al-Fahm Art Galler

The city of Umm al-Fahm in northern Israel is known as a political flashpoint, but it is trying to make a name for itself in a new field, as the home of the first Israeli Arab gallery of contemporary art.

The twin aerial photos displayed at the entrance to the Umm al-Fahm Art Gallery were taken from the exact same angle, 65 years apart. The frame on the left shows a luscious green mountain range, the northern edge of the Samarian Mountains, whose triple crests rest like the paw of an ancient monster on the edge of a dirt path running through the valley below. A few houses are scattered at the top of the mountain. They are the village of Umm al-Fahm, population 2,000, in the year 1944.

The frame on the right is filled with houses from end to end, covering every surface, replacing the green vegetation with gray concrete and threatening to spill off the monster’s paw right into the highway that was once a dirt road. The caption reads: City of Umm al-Fahm, 2007, population 45,000.

Besides the monumental growth and overcrowding, the pictures, part of the exhibit “Photography, History, Identity,” on view last year, revealed a lesser-known quality of the city that has become an uneasy symbol of Israel’s large Arab minority: its beauty. The images, which can now be seen in the gallery’s archives, also allow visitors to view the Israeli Arab experience in a new light.

And that is one of the goals that prompted Said Abu Shakra to open the first gallery of contemporary art in the Israeli Arab sector. From its humble beginning in 1996 to its current effort to become a full-fledged museum, Abu Shakra has always seen the museum-to-be as no less than a vehicle to transform society.

“Umm al-Fahm has a stigma as a place you shouldn’t go to, a dangerous place,” he said. “We believe prophecies fulfill themselves. If people say it is dangerous, it will be. If people say it is a place of art, it will be.”

The gallery, www.umelfahemgallery.org, which shows about four exhibits per year, specializes in contemporary Israeli and Palestinian artists as well as inviting international artists to exhibit. Over the years it has displayed the works of Israeli Jewish artists such as Menashe Kadishman, Dani Karavan, Uri Lipschitz, Meir Pichhadze and Micha Ullman; Israeli Arab artists including Asad Izzi, Asim Abu Shakra (Said’s cousin), Walid and Farid Abu Shakra (Said’s brothers), Sharif Waked and Raeda Adon; and, from the West Bank, Palestinian artists Suleiman Mansour and Tayseer Barakat, among others.

“We didn’t want people to feel they are doing us a favor by exhibiting here,” said Abu Shakra. “We wanted it to be a privilege. Today, we are one of the best galleries in Israel.”

And the gallery successfully integrates the town and visitors into the art experience. For example, a 1999 exhibit of work by Yoko Ono, which drew thousands of visitors from throughout the country, began with a billboard reading “Open Window”—the name of the exhibit—in Arabic, English and Hebrew installed next to the main highway at the entrance to the town. It was both an advertisement for and an integral part of the exhibit, suggesting to even casual passersby to open up and join “a dialogue of trust,” according to the exhibit catalog. Wish Tree for Peace, in the gallery courtyard, consisted of a lemon tree and a bronze plaque inviting visitors to whisper their wishes to the tree’s bark.

Jewish and Arab artists are often displayed side by side. They may be connected by the type of media used: A large charcoal sketch by Walid Abu Shakra showing the historic city of Acre at night is placed next to a large abstract in oil, charcoal and watercolor by Lipschitz. Or the common ground may be a shared ambivalence about Israeli society, as in the exhibit of the works of painters Asad Azi and Meir Pichhadze called “Foreign Language.” Azi is a member of Israel’s Druze community with relatives in Syria and Lebanon, and Pichhadze is an immigrant from Georgia. Pichhadze creates brightly colored oil paintings based on close-up photos of family members, with an other-worldly luminescence emanating from their skin and often echoed by a blazing skyline. A picture of a mustachioed, uniformed man standing at attention appears in many of Azi’s works, some with variations of the words “My Dady [sic] is a Dead Soldier.” Azi was 5 years old when his father was killed while serving in the Israeli security forces.

Other exhibits explore the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from an Arab perspective. A series of paintings of Palestinian detainees in positions used by Israeli interrogators, crouching with hands tied behind their backs, are painted in charcoal on paper, adorned with elements of Palestinian embroidery or images of olive trees, another national symbol.

Indeed, this northern Israeli city, the second-biggest Arab locality in Israel after Nazareth, has gained a reputation as a focal point of tension between the country’s Arab minority and the state. Israeli right-wing parties have suggested giving the town to the Palestinians in a land swap, a proposal the residents find both threatening and insulting. In October 2000, three residents of the town were killed by police in riots that swept through the Arab sector. In March 2009, members of the Israeli right marched through the town under police protection, setting off violent clashes in which 16 were wounded. The next month, the speaker of the Knesset, Reuven Rivlin, went to Umm al-Fahm on an official visit, including a stop at the gallery, and declared: “Umm al-Fahm is, was and will always be an Israeli city.”

With its 100-percent Muslim population, Umm al-Fahm, whose name means “source of coal,” is the capital of the Islamic Movement in Israel, a religious, social and nationalist group. The movement has run the city’s municipality for the last 20 years.

Although its official status was upgraded to city in 1984 because of the number of residents, Umm al-Fahm is essentially an overgrown village on a steep mountain range, whose tangle of nameless streets is often clogged with gridlocked traffic. Local legend has it that the buildings are so crowded together you can walk over two thirds of the town on the rooftops. As a hub for the surrounding rural area, 120,000 nonresidents come in to use Umm al-Fahm’s banks, health services and shopping centers. High unemployment and poverty are endemic. With these grave social, economic and political problems, cultural life was always perceived as an extravagance.

“There was no cultural life here to speak of,” said Abu Shakra of the decision to start the gallery 13 years ago. “We decided to take responsibility for our lives, and we decided we are capable and deserving of a cultural life.”

The 4th of 11 children in a family of artists, Abu Shakra aimed to establish a center of high-quality art, where standards would not be compromised by constraints of resources or community norms. The one concession he made to Islamic rules was to keep out nudity; but he proceeded to produce and present graven images and likenesses in paintings, sculptures, photographs and other forms of art that are forbidden in Islam.

The gallery receives funding from the Israeli Ministry of Culture, the local municipality and private supporters in Israel and abroad, but has suffered a painful shrinking of its resources due to the global economic downturn. All this comes in the middle of a campaign to build what will be the first museum of modern art in the Israeli Arab sector. After widely publicized false starts with two Arab architects—London-based Iraqi Zaha Hadid, who withdrew out of fear of being perceived in the Arab world as working for Israel, and the Israeli Arab Senan Abdelqader, whose plan was too expensive—the gallery declared a competition of architects, and ended up choosing Israeli architect Amnon Bar-Or from Tel Aviv. A four-acre lot was allocated for the museum and the plan is now moving through the bureaucratic pipelines while the $40 million for construction is being raised. Abu Shakra intends to build the museum in phases as the money comes in.

The gallery receives substantial support from both the Tel Aviv Museum and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The Tel Aviv Museum has hosted two fund-raising events for the Umm al-Fahm museum, free of charge, and trained curators. The Israel Museum has helped develop educational programs and collaborated with the gallery to create a community sculpture garden for Umm al-Fahm, which was inaugurated November 2009 on the city’s highest summit.

Israel Museum Director James Snyder is on the gallery’s advisory board. “We have worked together over the years,” he said. “The sculpture garden is an intercommunal project that reflects the architectural diversity of the city.” It involved bringing 3,000 Umm al-Fahm schoolchildren to spend a day at the Israel Museum Youth Wing for workshops on sculpture. The construction of the park, where some of the children’s artwork is on display, was documented by their grandparents on video.

Along with exhibiting quality art, the gallery also promotes art appreciation among people of all ages, serving as a cultural and artistic center for all artists in the Wadi Ara area in particular and Arab and Jewish Israeli artists in general and conducting a high-level cultural dialogue among artists from different sectors. It also organizes workshops for children and adults with the help of local artists and guest artists from abroad in painting, sculpture, ceramics, acting, arts and crafts, theater and music; using art to attract Jews to come and learn about their Arab neighbors and serve as a bridge between Israeli and Palestinian artists and artists in Arab countries.

The first challenge was acceptance by the local community. When Abu Shakra held the exhibit for Yoko Ono, he hoped the arrival of dignitaries, politicians, press and Israeli and international visitors would give the residents of Umm al-Fahm a sense of pride. He invited his neighbor Yousef, a gardener, to the opening. “The next day I saw him” recalled Abu Shakra, “and said ‘Hey Yousef, why didn’t you come?’ And he said: ‘I did come, with my two sons, but we stood in the door and looked in and when I saw all those fancy people inside with suits and ties, I looked at myself and said, this isn’t for me, and I went home.’ Yousef represents 80 percent of the people here. My challenge is how to reach these people and make them feel part of what we are doing.”

The dynamic 53-year-old Abu Shakra, a retired police officer who worked with juvenile delinquents, is constantly devising ways to involve the community in his work. He offers art classes, ballet classes for girls and summer camps. He brings in artists from all over the world, puts them up with families in the town and has local women earn an income by cooking for them. Ceramicists come in for one-day workshops, leaving their work at the gallery and local children paint it and the product is sold at the gallery gift shop. Abu Shakra is especially proud of his work with handicapped children and school dropouts.

“At first we had a lot of enemies,” said Abu Shakra. “What we are doing embarrasses not only those who claimed we could not make a difference but also the establishment and the leadership of the Arab population. For 50 years they have been taking people to demonstrate. Why don’t they take people to build?”

Abu Shakra has been walking a tightrope between his community and the establishment and between his passions and his responsibilities his whole life. As a young man, he wanted to follow in the footsteps of his older brother, Walid, and become an artist, but he had to work to support his family. At 21, he joined the Israeli police, from which he retired six years ago after 25 years of service.

Today, he teaches Israeli Jews and Arabs to live together with respect, organizing joint exhibits and workshops. At the same time, Abu Shakra sees highlighting the Palestinian identity of his constituents as an important part of his mission. A documentation project of the Wadi Ara district in which Umm al-Fahm is located, including a photo- and oral-history archive and exhibit, has become a central plank of the museum plan.

Under the tutelage of documentation experts, interviewers are collecting oral histories from 500 elderly residents of the district and storing them in the gallery’s historical archive. The photo exhibit launching the project, “The Photographic History of Umm el-Fahem (sic) and Wadi Ara,” displaying hundreds of historical photographs, covers the walls of the entire gallery and has been running for a full year.

Some portraits were taken from residents’ homes and are deliberately hung in their original frames to maintain their authentic flavor. A number of pictures were collected from historic archives and personal collections abroad. And many others were gathered from Israeli institutions that have taken photographs of Arab life over the years, such as the Army or Jewish photographers from nearby kibbutzim.

“For many years, the Arabs did not have cameras,” explained Abu Shakra. “These were the only sources that were available.”

Because of the identity of the photographers, there are many images of the encounter between the Israeli military and the local population. One from 1948 shows the local leadership surrendering its arms to the Israeli forces after the State of Israel was established and Umm al-Fahm became part of it; the border between Israel and the Jordanian-controlled West Bank was drawn along the southern end of the village.

Another picture shows makeshift Israeli flags the Arabs were commanded to draw by hand and hang on their homes. Yet another shows a group of local girls singing songs in honor of Israeli Independence Day in Arabic.

But not all the pictures paint a history of humiliation and defeat. One, of Arab women carrying sacks of earth on their heads during an archaeological excavation in the 1930s, is hailed by historians as critical evidence that Arab women did indeed work at that time to support their families, contrary to the common perception that women did not work outside the home.

Abu Shakra believes strengthening the Palestinian identity of Israel’s Arab minority does not threaten Israel’s Jewish identity but empowers both sides to build their joint future: “We say Palestinian memory and Jewish memory must live alongside each other. We have to look each other in the eye.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] could stand for their progressive bona fides to the outside world. Hadid returned the favor: She backed away from a museum project in Israel in the mid-2000s, concerned that it would alienate prospective Arab […]