Issue Archive

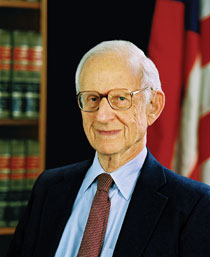

Profile: Robert Morgenthau

Most district attorneys garner little attention outside their local constituencies: So how did this man’s career inspire the creation of one of television’s most popular lawyers?

Robert M. Morgenthau’s downtown New York office could qualify as a museum. Here, the 87 years of his life—the last 32 as Manhattan district attorney—unfurl like the flags his youngest daughter likes to paint, a pastiche of American history colored by his extraordinary heritage.

The walls teem with photographs of family, colleagues and mentors: Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy and other greats including his own father, Henry Morgenthau Jr., who led rescue efforts for Holocaust survivors as secretary of the treasury under Roosevelt, and Herbert Lehman, his maternal great-uncle, governor of New York from 1933 to 1942 and United States senator from 1949 to 1957. His grandfather, Henry Morgenthau, was ambassador to the Ottoman Empire during World War I, raised funds for Jews in Palestine, helped found the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and spearheaded the advocacy for victims of the Armenian genocide.

But morgenthau has succeeded in earning legendary status in his own right, tenaciously holding on to his distinction as a nine-term district attorney, one of only three elected to the New York County post since it was established in the early 19th century. The far-reaching implications and high-profile nature of many of his cases—from winning convictions in the United Nations oil-for-food scandal to the successful prosecution of Tyco CEO Dennis Kozlowski—have catapulted an essentially local office into a potent national institution.

Morgenthau downplays his iconic status. “I try to think about what I’m doing myself and not about legends,” he says. “We prosecute cases without fear or favor…. Nobody should be above the law.” He also declines to single out major accomplishments. “Every case is important to the victim so I don’t like to distinguish,” he explains. “I’m proud of them all.”

His office of 525 assistant district attorneys and 725 support staff investigates and prosecutes some 100,000 criminal cases annually. During his tenure, he has increased the number of minority assistant district attorneys from 9 to 112 and the number of women from 19 to 249. Among his outreach efforts, he added a liaison to the gay and lesbian community.

Though critics contend that it is time for him to retire, he weathered a challenge in the 2005 election. The signs of seniority, however, are hard to overlook: He walks with a slow gait and has to propel himself from his seat with his hands when he stands. But he sees his age as an asset rather than a liability. “It means you’ve been around the block a few times,” he asserts. “You are not scared or worried about the impact of your decisions.”

“He’s smart, sharp and shrewd and can hold in his head a hundred times the stuff that younger people can,” says Pierre Leval, judge of the United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, who has known Morgenthau for over 40 years and was once his chief assistant district attorney. He praises Morgenthau as “one of the great public servants of the United States,” with an “astonishingly fine reputation of impeccable integrity….” Leval calls Morgenthau “the father of difficult and sophisticated white-collar prosecution,” which has become commonplace today.

Morgenthau has recouped over $170 million for the city and state in the past six years through prosecuting white-collar crime. He has shut down money laundering operations that sent $19 billion overseas, though he cannot say exactly how much went toward financing terrorist activities. “I don’t expect to prosecute [Osama] Bin Laden—if he’s alive,” Morgenthau says, “but we can play an important role in interrupting the flow of money.”

His detractors say he focuses on white-collar crime to the detriment of reducing violent crime. “That’s a canard,” he counters, trotting out statistics: Since he’s been district attorney, murders are down 85 percent and Manhattan is now No. 4 instead of No. 1 in violent crime. He has fought for rape law reform, even proposing to end the statute of limitations.

“The more complex and intricate the case, the better he is at it,” notes Ida van Lindt, his special assistant, who has been with him from his first day as district attorney. Morgenthau attributes his passion for justice to the lessons of the Holocaust. “I saw what the Nazis did and what happens when agents of the state ignore the law,” he remarks. His maternal grandmother’s first cousin perished in Treblinka. The Lehman Family Fund, started by his mother, brought 55 relatives to America.

Following his family’s example, Morgenthau was instrumental in founding the Museum of Jewish Heritage: A Living Memorial to the Holocaust in New York and has been chairman since its inception in 1997. In 2003, an 82,000-square-foot wing was named for him. “It’s important for people to understand what happens when criminals take over a government,” Morgenthau explains. “Our museum stands as a symbol of the power of renewal after catastrophe.”

Morgenthau is a “man of exquisite instincts,” says museum director David Marwell. “When he has a hunch or an idea about something, more often than not he’s 100 percent right. He is extremely careful and reads everything. Nothing gets past him. He has a tremendous sense of humor and a heart as big as New York City.”

In 1998, Morgenthau stopped two Egon Schiele paintings on loan to the Museum of Modern Art from being returned to Austria. “That was the first time anyone had challenged in American courts the ownership of art that had been stolen from Jews,” he says. “It caused a hue and cry because museums said I’d inhibit the show of art. But the result has been that museums have inventoried their collections and now have protocols in place. It’s made a huge difference.”

Aside from his work with the Museum of Jewish Heritage, the cause closest to his heart is the Police Athletic League, which he has chaired since 1963. “Some people climb the ladder of success and pull it up behind them,” he says. “I have always believed that you have got to make sure other people get the same opportunities you and your family have had.”

In 1990, he took two PAL teams to the Soviet Union, along with his wife, their son and his oldest grandson. On the way back, the family stopped in Mannheim, Germany, where Morgenthau’s grandfather was born. “I wasn’t walking around with a Star of David on my lapel,” he recalls, “but as we were getting into a cab to go to the airport the porter said, ‘I guess you’ll be flying El Al.’ I said to myself, ‘How much have things changed?’ I said to my son and grandson, ‘You’d better know who you are, because they know who you are.’”

Though he was raised in a family in which helping others was emphasized over ritual observance, Morgenthau is a life trustee of Temple Emanu-El in New York and still sits in his grandmother’s pew. “People need to know where they come from,” he asserts repeatedly. He traces his own background to German cigar maker Lazarus Morgenthau, who emigrated from Germany to New York in 1866, and Mayer Lehman, who emigrated in 1850 from Bavaria to Montgomery, Alabama, where he opened a small shop called Lehman Brothers with one of his two brothers. After the Civil War, the brothers moved to New York, helped establish the Cotton Exchange and later built the investment bank that bears their name.

His mother was involved in the women’s rights movement and the New York Democratic Committee, and was “very close to Mrs. [Eleanor] Roosevelt,” Morgenthau says. He points to a picture of the two women on horseback and recalls spending Election Days and some New Year’s Eves together. “The rule in the family was that nobody could criticize either Mrs. Roosevelt or my mother’s family.” His brother, Henry III, a retired executive producer of a public television station in Boston, is the author of Mostly Morgenthaus: A Family History (Ticknor and Fields). His sister, Joan Morgenthau Hirschhorn, a doctor, is associate dean and founder of the Adolescent Health Center at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York.

Morgenthau joined the Naval Reserve while still at Amherst College, and after graduation, joined the Navy full-time. He served for almost five years on three destroyers during World War II, attaining the rank of lieutenant commander and earning Bronze and Gold Stars. He speaks with pride of standing up for his black shipmates and recalls his luck at escaping the sinking of the U.S.S. Lansdale and the 18 kamikaze and torpedo attacks against the U.S.S. Harry F. Bauer. He still attends and hosts ship reunions.

With a degree from Yale Law School, Morgenthau joined the firm of Patterson, Belknap & Webb. His first boss, Robert Patterson, remains one of his heroes. A federal appellate judge and secretary of war before he returned to private practice, Patterson believed everyone should devote a third of one’s time to public service. Morgenthau accompanied Patterson on every trip except one, because he was on deadline for a brief; Patterson’s plane crashed with no survivors. “Above all, you gotta be lucky,” the district attorney says.

Morgenthau organized a successful campaign for John F. Kennedy in New York; in 1961, Kennedy appointed him United States attorney for the Southern District of New York. He ran for governor in 1962 but lost, resuming his job as United States attorney until then-president Nixon forced Morgenthau, a Democrat with upward ambitions, to resign in 1970. He returned to private practice before winning the district attorney post in 1975.

Fans of Law & Order may know that Adam Schiff, the television series’ first district attorney played by actor Steven Hill, is reputed to be modeled on Morgenthau. “I was a fan,” Morgenthau says. “They get a lot of their cases from us. [Steven Hill] was here a couple of times, and I told him he should let me know when he retired so I could apply for his job. It paid $25,000 per episode. But he didn’t tell me.” Morgenthau says he rarely watches the show anymore because his son and daughter prefer wildlife and cooking shows. He tends to watch the news.

His seven children span five decades in age: five children with his first wife, Martha, who was not Jewish and who died of breast cancer in 1972, and two from his current marriage to Lucinda Franks, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist 30 years his junior (who also is not Jewish). He has five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren as well. His hobbies include fishing and boating (on vacations), tennis and growing vegetables (heirloom tomatoes are his favorite). He maintains homes in New York City and upstate in East Fishkill.

A plaque on his wall given by his assistants reflects the talents that have made him champion of the downtrodden and cheerleader to a dedicated staff. It reads, “To the boss at 80: An unusual man whose eye for people is unique. He gave us all a chance to be the best, which only our own respect and affection can repay him.”

He describes the legacy he would like to leave his family: “Public service,” he states concisely. It is an inheritance that mirrors his own.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply