Issue Archive

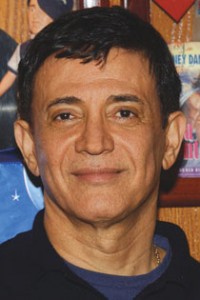

Profile: Jamie Masada

A spirit of generosity, altruism and humor have followed this comedy insider from Iran to Israel and Los Angeles, from poverty to wealth and success.

At the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Laurel Avenue in Los Angeles sits the Laugh Factory, aka The World Famous Laugh Factory. The title is presumptuous, maybe, but it just so happens to be true.

If you’re a fledgling comic, this comedy club is one of a handful of stages you dream of working. Comedians like Richard Pryor and Rodney Dangerfield were regulars here. Today’s up and comers work out bits here, too, and established stars like Chris Rock test new material on this stage when the mood suits them. As long as they check in with Jamie Masada first.

Masada may have also started out a comic wannabe, but today, at 42, he is famous as owner of the Laugh Factory, entrepreneur, talent promoter and philanthropist. Besides the original in Los Angeles there are Factory locations in New York City and Long Beach, California. Add to that various television and film projects and you begin to appreciate Masada’s influence in the comedy world.

“Everybody has a chance in this country,” he says during a reflective moment one warm afternoon in his office, a forest green-painted room in an old craftsman-style house that doubles as Laugh Factory headquarters. A slight, frail-looking man with smooth olive skin, Masada embodies the American dream.

Jamie chaim masada was born in israel in 1964, but his family returned to their native Iran when he was only 2. The Masadas remained in Iran until 1976, when political turbulence forced them to go back to Israel, where they lived in the Carmel hills of Haifa.

His parents could barely make ends meet, but they were “rich in love and caring,” he says. His father was an entertainer, accordion player and sometime cantor when a congregation needed a good voice. He made sure to bring his young son with him to the parties he worked. Masada’s job was to tell jokes. “I wasn’t a good joke teller, but I was very thin, and they had food there,” Masada recalls.

At one such event, an American producer was watching. He saw Masada perform and assured his parents he had a future in show business. His mother and father saw it as an extraordinary chance and somehow found the money to pay for a plane ticket for their son.

“America was the land of opportunity, and the man was telling my father it was a ticket to get out of poverty,” Masada explains. And so, with $850 in his pocket and propelled by his parents’ dream, the 14-year-old flew from Israel to Los Angeles.

On arrival, however, Masada learned that the producer his parents trusted with their money and his future was long gone. “I never told my parents because it would make them feel guilty,” he says. Instead, he befriended an apartment manager who let him sleep on a couch in a garage just a few blocks down Sunset Boulevard from where his comedy club stands today. To make ends meet he worked various odd jobs. Within nine months, he had rented an apartment and was going to school to learn English.

Masada stuck to the Sunset Strip and happened upon the Comedy Store club one day. Desperate to fill a slot in the night’s lineup, veteran comedian and Comedy Store owner Sammy Shore, father of actor Pauly Shore, put Masada on the bill. But his turn as a comedian didn’t last long.

One night, Masada says, “I was working at [the Comedy Store] and this one comedian had this big agent coming. They said, ‘You have to put somebody really bad in front of you, to make you look good,’ and everybody said ‘How about Jamie?’ and I heard it.”

Having failed onstage, masada refocused his efforts on behind-the-scenes comedy. It was 1979, and comedians were striking, angry at the industry standard of not being paid for standup. So when he happened by a building for rent on Sunset Boulevard, he asked a friend to help him front the money and opened the Laugh Factory, the first comedy club to pay comedians.

“I was dishwasher, I was bartender, I was emcee, I was cleaning guy,” Masada recalls about the early days. “I created the sign, I did everything.”

By the time the club had hit its stride in the late 1980’s, comedy was enjoying a renaissance. Masada made the most of it with the Fox television series Comic Strip Live. He also branched out, becoming a talent manager and producer for movies such as Disney’s 1997 Rocket Man.

This month, he returns to the big screen as a producer for Behind the Smile, a feature film about the lives of comedians, starring brothers Damon and Marlon Wayans, John Belushi and Bob Saget. He is also working on a standup comedy reality show with cable channel TBS.

Masada gets home most nights between 1 and 3 A.M. and only sleeps about four hours, which helps explain how he manages all these projects and still remains true to his first love: the Factory. Last year, the club was chosen as U.S.A. Today’s Los Angeles pick for a round-up titled “Places to Sit Down and Watch Stand-up.”

Tuesday evenings at the Laugh Factory are Open Mic Night, and Masada observes the young comics from his regular seat, stage left, within reach of the light switch that cues comics that their time is up.

“One in a thousand make it,” Masada’s former assistant, Evan Rimer, says. “That’s an expression,” he quickly adds, “not an actual number.” Either way, it would be easy to say it is a waste of Masada’s time to be sitting there. But despite his busy schedule, if he is in town he shows up every Tuesday, making notes on each act and later offering tips on how to improve.

He is known in the industry for such kindnesses as well as his “eye for comedy gold,” says Stella Stolper, VH-1 vice president of celebrity talent and creative development and a friend of Masada’s. “He’s pretty much worshiped by all because he’s a rarity in the business, where you find someone who’s honest and decent and looking out not for themselves but for the good of the cause.”

His friend, comedian and actor Larry Miller, likewise praises Masada’s abilities: “He has an extraordinary eye for talent and ideas for how to move people’s careers along.” Miller said he also shares a love of Israel with Masada. “If I was going to Israel,” Miller said, “he would tell me ‘I want you to spend some money there…. I’ll give you the money.’ It’s an important gesture.”

Though Masada no longer has family in Israel—his parents are deceased and his remaining family, his grandparents, are still in Iran—he continues to visit the country. He is currently working with the Israeli government to bring a comedy festival there, which he said should be happening around the end of the year.

When asked about family today, Masada likes to tell people he has 540 kids. “That’s my comedy camp,” he says. The Laugh Factory Comedy Camp offers underprivileged inner-city children from Los Angeles, ages 8 to 16, the opportunity to learn about standup comedy. Since 1984, Masada has recruited the hottest comedians to teach their craft. At the end of the 10 weeks, after a final performance on the Factory stage, each child receives a certificate of completion.

PBS aired a documentary about the program in 2002, titled Stand Up: A Summer at Comedy Camp. That year, participating comedians included Paul Rodriguez, Rob Shneider, Shawn Wayans and Jamie Foxx.

Teaching troubled children about standup may seem odd, since most will never go on to become comedians. But more than comedy, the program teaches confidence and coping skills.

“Jokes are problem solving,” Shneider told the cameras. “It’s a way of dealing with life…. Laughter is a natural healer.”

The camp is as much Masada’s passion as are his business endeavors. Indeed, he seems to thrive on a tightly packed schedule. On a typical day he goes to the office in the morning, returns home to feed his five dogs—all rescues—goes back to the office and then makes his way to the club for the rest of the night. “I was going out with a nice Jewish girl, but she said I’m a workaholic,” he recounts, laughing.

But Masada performs both his professional and charitable work joyfully, never forgetting his own rough past. “You don’t do it for people to get to know about it,” he explains. “You do it because God gives you the chance to give back.” In recognition of his charitable work and his Persian Jewish heritage, last month Masada received the Ellis Island Medal of Honor, given to American citizens of diverse origins who have made a contribution to the nation.

He is not a particularly religious man, but “we get [inspiration] from our roots, absolutely,” he says. Since 1994, Reform Rabbi Bob Jacobs has collaborated with Masada to offer High Holiday services at the Factory to Jews seeking a communal experience. Jacobs conducts the free services along with Cantor Sue Karlin. “Last year I had 600 people come for Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur,” Masada recalls. “People stood on the sidewalk and we put monitors and speakers outside.” He also opens the Factory for free meals on Thanksgiving and Christmas.

Masada’s other philanthropic efforts include visiting sick children in the hospital. It was just such a visit that got him caught up in the Michael Jackson molestation trial last year. Masada was a witness because he had arranged the original meeting between Jackson and his accuser, a cancer patient whose dying wish was to meet the pop star. But with the trial now over, he has put it behind him. “I’m not judge and jury to say [Jackson is] guilty or not guilty,” Masada says. “We all have to live with our own conscience.”

Back at the Laugh Factory, the lights are dim, but this isn’t the dingy smoke-filled club of the past. Masada says that is not what people want nowadays. The building has been renovated, but what remains is the feeling that this intimate space, with its classic red leather and gold accents and signature logo with neon arches on stage, has been around a while. However, Masada says, the most significant change in comedy since he started is the pace.

“People used to be more patient,” he explains. “Now you’ve gotta try to make comedy fast. Everything is fast, fast, fast.”

The pace seems just right for a man who has his hands in several projects at the same time. Yet, one wonders how Masada does all that he does and still sleeps even the four hours he confesses to.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply